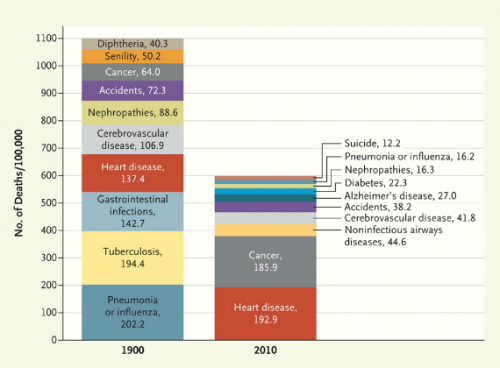

The Washington Post has provided an image from the New England Journal of Medicine that illustrates changing causes of death. Comparing the top 10 causes of death in 1900 and 2010 (using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), we see first that mortality rates have dropped significantly, with deaths from the top 10 causes combined dropping from about 1100/100,000 to about 600/100,000:

And not surprisingly, what we die from has changed, with infectious diseases decreasing and being replaced by so-called lifestyle diseases. Tuberculosis, a scourge in 1900, is no longer a major concern for most people in the U.S. Pneumonia and the flu are still around, but much less deadly than they used to be. On the other hand, heart disease has increased quite a bit, though not nearly as much as cancer.

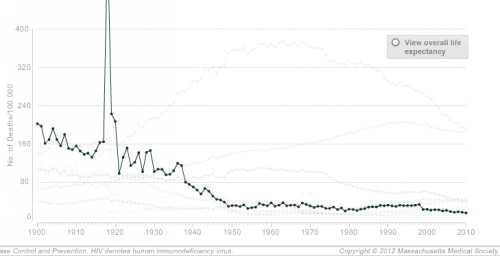

The NEJM has an interactive graph that lets you look at overall death rates for every decade since 1900, as well as isolate one or more causes. For instance, here’s a graph of mortality rates fro pneumonia and influenza, showing the general decline over time but also the major spike in deaths caused by the 1918 influenza epidemic:

The graphs accompany an article looking at the causes of death described in the pages of NEJM since its founding in 1812; the overview highlights the social context of the medical profession. In 1812, doctors had to consider the implications of a near-miss by a cannonball, teething could apparently kill you, and doctors were concerned with a range of fevers, from bilious to putrid. By 1912, the medical community was explaining disease in terms of microbes, the population had gotten healthier, and an editorial looked forward to a glorious future:

Perhaps in 1993, when all the preventable diseases have been eradicated, when the nature and cure of cancer have been discovered, and when eugenics has superseded evolution in the elimination of the unfit, our successors will look back at these pages with an even greater measure of superiority.

As the article explains, the field of medicine is inextricably connected to larger social processes, which both influence medical practice and can be reinforced by definitions of health and disease:

Disease definitions structure the practice of health care, its reimbursement systems, and our debates about health policies and priorities. These political and economic stakes explain the fierce debates that erupt over the definition of such conditions as chronic fatigue syndrome and Gulf War syndrome. Disease is a deeply social process. Its distribution lays bare society’s structures of wealth and power, and the responses it elicits illuminate strongly held values.

Comments 18

Yrro Simyarin — June 25, 2012

That's such a cheerful chart. Nearly all of our causes of death have been replaced by "being old."

Rosario — June 25, 2012

It's not so much that there is more cancer and heart disease, but that people who would previously have died of things like flu and tuberculosis now survive, and they do have to die of *something*...

Hanover — June 25, 2012

Perhaps the Christian Scientists have it right.

amelia — June 25, 2012

What Yrro and Rosario said. I think it's important not to buy into the ideology implied by the term "lifestyle diseases" -- namely, that no one would get these diseases if they made the right lifestyle choices.

Erational — June 25, 2012

Agreeing with the other comments that referring to these as 'lifestyle diseases' is problematic (the author does seem to imply recognition of the problem with this). With some notable exceptions (viral- and bacterial-triggered cancers, smoking-induced cancers and cardiovascular diseases, alcoholic liver disease, etc) the strongest risk factor is generally genetic predisposition. Involuntary exposure to chemicals from plastics, pesticides, etc is another strong factor, but one that is extremely difficult for an individual to avoid, unless they have a significant amount of time, money, and energy to devote to the project -- and, even then . . .

People today, on the whole, are much more knowledgeable about health and nutrition, and cultivate health with a dedication unmatched in previous eras. Everyone has to die of something, however -- even those of us who "do everything right" according to prevailing health ideology.

Michelle C. Funk — June 25, 2012

Wow. That was quite the shout-out to eugenics. I've never particularly well-informed about eugenics, but I wasn't aware that it was ever so accepted in the medical community as a long-term solution for disease.

John Bailo — May 24, 2013

Why were accidents so much more lethal in 1900? Supposedly we're now surrounded by unsafe machines like cars as we absorb carcinogens in our sprawling unwalkable suburbs.

Mark Evans — July 29, 2015

It's interesting that cancer has gone up so much when men smoked MUCH more in 1900. Women smoked less - at least in public. It would be interesting to see the cancer figures in 1950 or 1955, halfway through the period & at the height of smoking as an acceptable social norm for both sexes.

CO TY WIESZ O NASZYCH CZASACH? | VidShaker — June 14, 2017

[…] Historical Changes in Causes of Death […]

CO TY WIESZ O NASZYCH CZASACH? – PIMEO.pl — July 4, 2017

[…] Historical Changes in Causes of Death […]