The phrase “service economy” — commonly used to describe the U.S. economic profile these days — refers to a decrease in manufacturing (where we make things for people) and an increase in the service sector (where we do stuff for people).

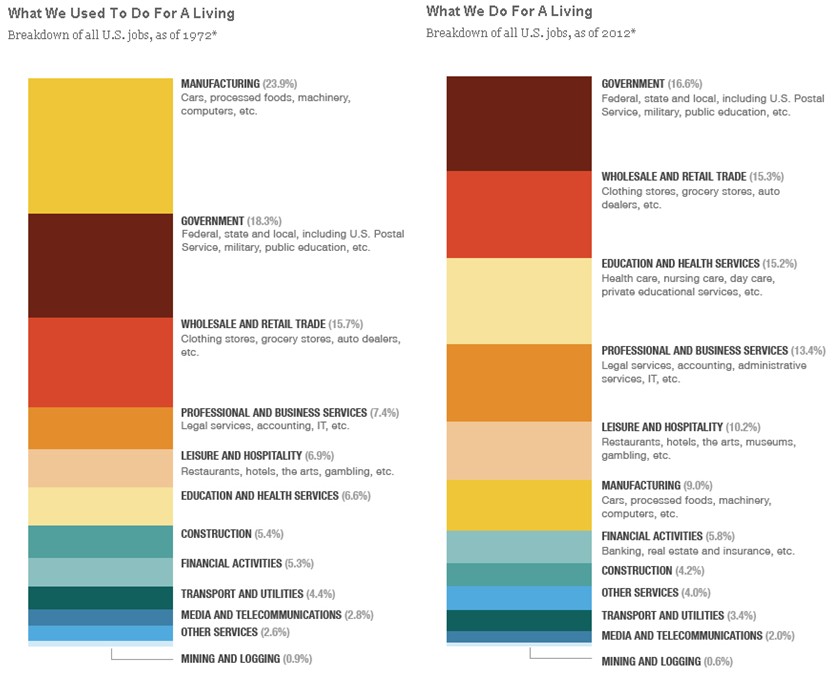

Planet Money put together stacked bar graphs to illustrate the increasing importance of service in our economy (1972 on the left, 2012 on the right). Manufacturing (making things) is in yellow, so you can clearly see its decline in prominence. Service sectors include “professional and business services,” “leisure and hospitality,” and “education and health services.”

So, when people talk about the move to a service economy, these are the changes they’re talking about. We also see the “servitization of products” (don’t you love academics?), or a tendency for products to come with more and more service. A restaurant, for example, offers a product (made by the chef), but also a degree of service (offered by the wait staff). Both the quality of the food and the service vary as you move from fast food restaurants to high end eateries. When we see a servitization of products, we see a ratcheting up of the level of expected service that attends any given product.

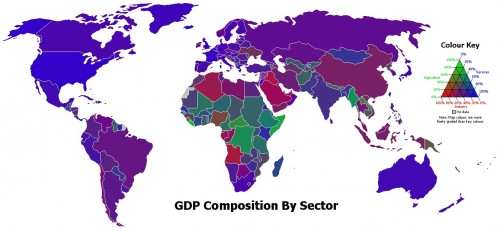

The U.S. economy, by the way, is more heavily characterized by service than most of the world. The map below is colored to indicate the relative balance between service (blue), manufacturing (red), and agricultural (green) industries in each state. You can see that the U.S. is among the bluest country on the map:

One of the concerns with the move to a service economy is that service jobs on the low end of the occupational hierarchy tend to be “bad” jobs, while manufacturing jobs, even when they’re on the low end, tend to be “good.” Service jobs are “bad” in the sense that they tend to have low wages, underemployment, little chance for advancement, and poor or no benefits. We’re talking, here, about jobs in sales, cashiering, food preparation, and the like. Because of this tendency, the move to a service economy is taking some of the blame for the shrinking of the middle class.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 27

Xiao Mao — June 20, 2012

Wow. I'm not surprised by the numbers, but dang that map is cool... now can you imagine what our GNP would be if it included all of womens' UNPAID LABOR? Such as child rearing, laundry, cooking, house cleaning, etc. I imagine it would add billions of dollars to that number.

Understanding the Service Economy « Welcome to the Doctor's Office — June 20, 2012

[...] from SocImages [...]

Aaron B — June 20, 2012

Indeed, many service jobs are worse jobs than manufacturing jobs, but I think it needs to be said that this is because service industries didn't benefit from unionization and activism that led to higher wages, better job security, etc. Were the service sector better organized, I suspect these jobs wouldn't seem so inferior. Not that I think you misstated anything, but this seemed worth clarifying.

It's also interesting to see that France is one of the only other countries as blue as the US. It's suffered from rapid deindustrialization and low union membership, but past labor activism has helped maintain some benefits, and most workers, in industry at least, still benefit from union contracts. But I wonder how the status of French service jobs compares to those in America...

decius — June 20, 2012

Well, the entire drop in manufacturing was taken up by increases in health services and professional services- the percentage in trade remained roughly constant, and the numerical increase in hospitality is modest.

The drop in manufacturing is partially associated with the high standards of working conditions associated with manufacturing. The CNC machine operator replaces dozens of machinists, at lower overall costs. When low-level service jobs are replaced by machines or outsourced overseas, then the service jobs will improve to the level that manufacturing is. Also, unemployment will rise until the economy expands to meet the new availability, and education expenses will rise to reflect the higher skills required of entry level, part time, easily replaced employees.

NuclearSubway — June 21, 2012

The purpose of manufacturing is to manufacture things.

This is a point so obvious that it bears belaboring, because this analysis seems to have missed it. Manufacturing has only been on the decline for the past few years due to the depression. Before then, manufacturing output had continuously risen in both per capita and absolute terms, and until recently, the United States was the most industrially productive nation on Earth, until it was overtaken by China.

Again, the purpose of manufacturing is to manufacture things, not to give people something to do. If you want that, just start paying people a lot of money to dig and refill holes somewhere.

» Some supporting info on The New Jim Crow… Introduction to Political Science 101 class blog — November 19, 2012

[...] The changing workplace [...]

A Primer on the Service Economy | GLEAMsocial — June 21, 2016

[…] Source: A Primer on the Service Economy | Sociological Images […]