Cross-posted at Family Inequality.

There’s an interesting example of how to interpret scientific results — and draw policy implications from them — from the world of birth practices and safety.

The subject of the debate is a major new study from the British Medical Journal. The study followed more than 60,000 women in England with uncomplicated pregnancies, excluding those who had planned caesarean sections and caesarean sections before the start of labor. They compared the number of bad outcomes — from death to broken clavicles – for women depending on where they had their births.

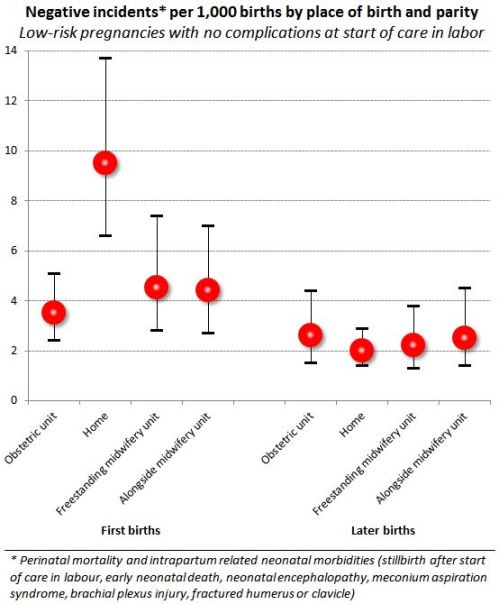

One comparison stands out in the results. From the abstract: “For nulliparous women [those having their first birth], the odds of the primary outcome [that is, any of the negative events] were higher for planned home births” than among those planned for delivery in obstetric units. That is, the home births had higher rates of negative events. The difference is large. Here’s a figure to illustrate:

The error bars show 95% confidence intervals, so you can see the difference between home births and obstetric-unit births is statistically significant at that level. These are the raw comparisons, but the home-versus-obstetric comparison was unchanged when the analysts controlled for age, ethnicity, understanding of English, marital or partner status, body mass index, “deprivation score,” previous pregnancies, and weeks of gestation. Further, by restricting the comparison to uncomplicated pregnancies and excluded all but last-minute c-sections, it seems to be a very strong result.

But what to make of it?

In their conclusion, the authors write:

Our results support a policy of offering healthy nulliparous and multiparous women with low risk pregnancies a choice of birth setting. Adverse perinatal outcomes are uncommon in all settings, while interventions during labour and birth are much less common for births planned in non-obstetric unit settings. For nulliparous women, there is some evidence that planning birth at home is associated with a higher risk of an adverse perinatal outcome.

But in what way do the results “support a policy”? The “higher risks” they found for planned home births are still “uncommon,” by comparison, with those in poor countries, for example. But the home birth risk is 2.7-times greater.

The Skeptical OB, who is a reliable proponent of modern medical births, titled her post, “It’s official: homebirth increases the risk of death.” She added some tables from the supplemental material, showing the type of negative events and conditions that occurred. Her conclusion:

“In other words, any way you choose to look at it, no matter how carefully you slice and dice the data, there is simply no getting around the fact that homebirth increases the risk of perinatal death and brain damage.”

I guess the policy options might include include whether home births should be encouraged, more regulated, covered by public and/or private health insurance, banned, penalized or (further) stigmatized.

Home birth seems safer than letting children ride around unrestrained in the back of pickup trucks, which is legal in North Carolina – as long as they’re engaged in agricultural labor. On the other hand, we have helmet laws for kids on bicycles in many places. And if a child is injured in either situation, hopefully an ambulance would take them to the hospital even if the accident were preventable.

In other words, I don’t think policy questions can be resolved by a comparison of risks, however rigorous.

Comments 54

QoB — December 20, 2011

Admittedly I read this quickly, but that chart shows only negative outcomes for the babies - did the study cover the women too?

Shinobi — December 20, 2011

So what exactly should we base policy on? Whether or not it sounds like a good idea at the time?

Umlud — December 20, 2011

Does anyone know what the definitions of "freestanding midwifery unit" and "alongside midwifery unit" are, in the way in which they are used in the paper? I am not familiar with either term, and a Google search doesn't shed much light. Also, does "home" mean birth at home without a midwife or doctor?

These are very specific terms that neither the authors nor the OP actually define.

Emmag — December 20, 2011

I would like to see a comparison of types of negative outcomes. I think skeptical OB may be making too far reaching a conclusion when she says home birth increases risk of brain damage and death when the article compared amount of negative outcomes--from death to broken clavicles. Brain damage, death, and broken clavicles are quite different in degree of negativity.

QX — December 20, 2011

To me, these results support a policy of:

- figuring out why first-time mothers are choosing home births and

- reforming other birth settings to make them more appealing to first-time mothers.

C. D. Leavitt — December 20, 2011

Why are planned home births for subsequent births the safest option while for the first birth they're the most dangerous option? In subsequent births the safety ratios are reversed with an obstetric unit as the most dangerous. Why? There are some serious and bizarre questions suggested by those numbers.

Apwheele — December 20, 2011

Regardless of the validity of the study, the logic of your next to last paragraph (and the subsequent conclusion you present in your final sentence) are ridiculous. Other laws are totally non-sequitur to this research, and hence potential policy choices related to birthing (like the ones you mention in the post) can be reasonably differentiated between. One stupid decision does not justify another one.

Anonymous — December 20, 2011

Studies like this, and the briefer press releases and articles always leave a lot of questions-

How is 'negative incident' defined in the study? If this includes a midwife noticing a problem and making a non-emergency decision to transfer to a hospital- than the results are misleading especially to those not familiar with home birth.

How are negative hospital experiences and unnecessary interventions that are more common in a hospital setting accounted for in the study?

If the study shows there is a slightly higher chance of 'negative outcome' in a home setting, is that significant? At home, midwives do not perform csection, induce or use drugs- therefore less of the problems associated with these interventions occur in a home setting. If asked, a huge percentage of women considering or choosing home birth will say that they are trying to look at the risks of home birth and compare them to the risks of hospital birth (ie unneccessary interventions, lack of good midwifery support, policies and procedures that inhibit their experience) because they want to avoid unnecessary interventions and give birth in a supportive, peaceful environment where they feel more comfortable. If they choose a midwife- then they are also looking for someone to support and guide them, including deciding when it is time to intervene, to transfer, etc.

I'm doubtful that the researchers found a way to account for the risks of modern birth management in hospitals where policies and practice vary so greatly. These home birth comparisons do not yet offer a realistic comparison of risks. The study numbers show there was an increase of about 4 events per 1000 births. And if 1000 women went to a hospital instead of having a home birth- wouldn't about 30-50% of them end up with a c-section, if we use the typical csection rate (although, maybe the UK has a much lower rate than the US)? If the homebirth c-section rate was only 10-15% (or less) - how do we measure the different outcome? There are also very important differences between maternity care in England and the US, most notably the role of midwives.

Finally, the author writes.... "The Skeptical OB, who is a reliable proponent of modern medical births..." which leads me to ask how do you define 'reliable' and 'modern medical birth'? She's controversial, for sure.If the author only read Dr T's article, I think they should have looked for other viewpoints to complete the picture. Dr T. does have some valid points regarding midwifery in between a lot of homebirth hate and ranting, however I get the impression she'd rather we ignore the problems the US has with maternity care such as high costs, poor outcomes, and the ever increasing rates of c-sections. There are a lot more birth advocates out there who are seeking to impart change collaboratively that could offer reliable opinions on this subject - on both sides.

Anonymous — December 20, 2011

So it looks like the important part is transfer time? That could have policy implications, either for research into improved on-site interventions or expansions of home-like environments close to a hospital as alternatives. Better on-site interventions could have enormous benefits for rural births or export to countries without ready access to ob departments.

Rather than taking such statistics as set in stone, they should be jumping-off points for root cause analysis.

ASG — December 20, 2011

For an individual woman giving birth to her first child, the likelihood of a negative outcome is 1% in a planned home birth and 0.4% in any other setting (if you'll permit a hasty summary from the chart). As an individual, the difference between 1% and 0.4% might seem negligible.

There were over 700,000 births in England and Wales in 2009. That 0.6% difference is up to 4,200 negative outcomes. (Clearly not all of the births were to nulliparous women, but two minutes of googling didn't find me better statistics.) As a matter of public health, this is a big deal, especially because it is significant at a 95% confidence level.

There are any number of other thing that can be done to improve the health and safety of women and children, but this is the way that obstetricians have of impacting public health. Rather than view this result as an argument for medical intervention in first births, might this be a motivation for further study to determine how to improve the outcomes of nulliparous home births? Or maybe it is an argument for medical intervention in nulliparous birth. In any case, the fact that other actions would have a positive impact on maternal and perinatal health are not strictly relevant.

Praminthehall — December 20, 2011

I can't believe any credible academic would reference anything "The Skeptical OB" says on her blog. Amy Tuteur is not a licensed physician and has not practiced medicine in years and years. If you read blogs in the area of birth (which I do as part of my research), you can see that she occupies most of her time by bullying proponents of non-interventive birthing and maternal decision making in the birth process. Whenever someone argues against her point of view, she accuses the person of not knowing how to interpret scientific evidence (disclosure: this charge has been leveled against me, even though I am a methodologist and teach research methods to graduate students at an R1 university). She has no respect for qualitative research or for any outcome that deals with psychosocial health. In her opinion, as long as the baby is born physically healthy, any intervention or procedure is acceptable and its necessity unquestionable. She is heartlessly nasty to mothers who are unhappy with or even traumatized by their birth experiences. In other words, she perpetuates the very culture that drives mothers to birth at home, even when there are evident risk factors. I'm sure that she will never mention that adverse outcomes are LOWER in homebirths for second and higher order births.

Critiques of the study referenced above that Skeptical OB would never mention: The report above does not differentiate by licensing of birth attendant, which is different in Britain and thus limit generalizability of findings to the U.S. In the U.S., birth outcomes are different among certified nurse midwives (CNMs) and direct entry or certified professional midwives (CNM births have better outcomes than those of any other type of birth attendant, including OBs, but of course they would not handle the high risk births that OBs are obligated to attend). As others have pointed out, it also doesn't disaggregate negative outcomes; in this study, a broken clavicle would be a bad outcome, but a cesarean to prevent a broken clavicle would not, even though an infant's broken clavicle heals much more quickly and easily than a mother's cesearean.

Antigone — December 20, 2011

How about we give women the facts and let them make the decision? It shouldn't be "home births are not as safe, so what?" Some women might say "so what" and that is their decision, but there are many women who have been mislead by propaganda into thinking hospital births are less safe and will automatically result in terrible things.

Policy-wise, I really think the best course of action is to find a way to lower the amount of unnecessary interventions in the hospital environment, and provide a better atmosphere to facilitate natural birth, which is safer for low-risk women. This would allow women to have the best of both worlds. It shouldn't be a choice between a home birth (which carries the risk of being too far from medical professionals/equipment in an emergency), or a hospital birth where you are locked to a bed with monitors and IVs with a short timeline on how long you are allowed to labor before being giving Pit or a c-section.

Anna Geletka — December 20, 2011

I would also like explanations of "negative outcome". I would consider an unplanned c-section birth in a hospital to be a negative outcome, yet (correct me if I've read incorrectly) that doesn't seem to be counted as a negative outcome for women birthing in hospitals.

Rosie — December 20, 2011

Broken clavicles? WTF?

K00kyKelly — December 20, 2011

This seems like good evidence that policy should support making midwifery units more available. The risk levels seem to be on par with hospital births while giving women more flexibly (time, fewer interventions, etc) and lowering costs. Another good question would be if women who chose home births would have preferred to give birth in a midwifery unit if the option were available to them. Availably in this case could mean education (did they know it existed), financial (does their insurance cover it), location (is there one near where they live), and popularity (enough rooms to met demand).

Ryan Birkholz — December 20, 2011

Philip, could you explain why the policy implications need to be the same for nulliparous and multiparous groups? Can't the authors suggest restrictions on home births for first time births while encouraging home birth choices for subsequent births?

Amy Tuteur, MD — December 20, 2011

I cannot emphasize enough that the Birthplace Study does NOT show that home of second or subsequent babies is safe. To the extent that the Birthplace Study identifies a subgroup in which homebirth may be as safe as hospital birth, that subgroup is "women who can be relied upon not to experience any complication of any kind." In other words, homebirth is safe if nothing goes wrong. If there is any chance of anything going wrong, homebirth is not safe.

The exclusion criteria for the study were far more rigorous than the actual exclusion criteria for homebirth in the UK.

Women were excluded for:

Breech

VBAC

Twins

Elevated blood pressure

Gestational diabetes

History of previous shoulder dystocia

Low or high amniotic fluid

and a host of other major and minor risk factors

Women having a second or subsequent pregnancy were subject to an extra layer of scrutiny. How? Women were excluded if they had a problem in a previous pregnancy, even if there were no risk factors exclusive to the current pregnancy? Why? Because past obstetrical history reveals additional risk factors and is, essentially, another level of screening.

So, for example, a first time mother who will have a shoulder dystocia is included in the study, but a woman who had a shoulder dystocia in the past is automatically excluded by her first shoulder dystocia. Therefore, you would expect that the incidence of shoulder dystocia in the second group is going to be lower than the first.

Homebirth is safe only when nothing goes wrong. Since there is no way to predict with complete accuracy whether something is going to go wrong, even when there are no risk factors of any kind, homebirth can never be as safe as hospital birth.

BOB — December 20, 2011

One important point is that the higher risk is only for first deliveries. From the abstract: "For multiparous women, there were no significant differences in the incidence of the primary outcome by planned place of birth."

Kinelfire — December 21, 2011

The BBC, when covering this story, were at pains to stress that the increased risk was still less than 1%, if memory serves. Sufficiently small enough that I wasn't sure why it was as high in the headline ordering as it was, and why it couldn't be reported that hone birth was almost as safe as a medicalised birth. What was it about lies, damned lies and statistics...?

It's curious that 'doctor knows best' is still so prevalent in some areas of health and well-being.

K00kyKelly — December 21, 2011

This seems like good evidence that policy should support making

midwifery units more available. The risk levels seem to be on par with

hospital births while giving women more flexibly (time, fewer

interventions, etc) and lowering costs. Another good question would be

if women who chose home births would have preferred to give birth in a

midwifery unit if the option were available to them. Availability in this

case could mean education (did they know it existed), financial (does

their insurance cover it), location (is there one near where they live),

and popularity (enough rooms to met demand).

Anonymous — December 21, 2011

I don't think you can regulate home births considering the difficulty in knowing what is and isn't planned, but I definitely think that first time parents (note that not all people giving birth are women) should be informed of this study.

Anonymous — December 21, 2011

Aight, can someone explain what's with all the home birth chamioning here? Is it a liberal thing? Conservative thing? Money thing? Fear of hospitals thing? I'm just perplexed at how passionately you can defend something like this, especially since I wouldn't be able to ask you this if I'd been born at home.

nsv — December 22, 2011

I agree with those who suggest taking conclusions from sources other than only The Skeptical OB. Rixa Freeze, of Stand and Deliver, has a good round-up of sources at http://rixarixa.blogspot.com/2011/11/birthplace-in-england-tale-of-medical.html. Two of her linked sources I find especially useful: Lamaze's Science and Sensibility (http://www.scienceandsensibility.org/?p=3759) and Statistical Epidemiology (http://statisticalepidemiology.org/?p=64). Both of these sources are trained in evaluating exactly this sort of data and are able to consider their conclusions in a measured and non-inflammatory manner.

All that aside, any policy decisions should both look at data AND understand that some women will choose to give birth at home, no matter what the data say. Their reasons may be based in their religion, culture, previous birth trauma, finances, access to care, or simply a personal evaluation of the relative risks of home birth and hospital birth. (The latter, btw, is virtually the definition of the medical/legal/ethical standard of informed consent: being truly informed about the risks and benefits of the possible choices, and making a decision based on their personal values and needs.) Given that this is the case, to me it makes sense to work for reform in a number of areas: reform hospital-based care where it is deficient (the subject for its own post, surely), and make out-of-hospital birth as safe as it can be for the women who choose it, by licensing caregivers to assure at least a minimum level of competency (the same as for physicians), by building up formal relationships between the two systems of care in order to facilitate routine, urgent and emergent transport, and by giving out-of-hospital caregivers legal access to the tools needed (a very limited number of drugs, mostly, and oxygen) to provide safe care.

As for why there is such fervent defense of home birth, I will answer this from my own perspective, which I feel duty-bound to say is not necessarily shared by other home birth advocates: I view the right of a woman to choose her place of birth and to receive safe care as a reproductive justice issue, akin to the right to choose to use contraceptives, or to choose to become pregnant, or to bring up her child as her own. In addition, many of us believe that HOW a child is born is tremendously important both to the child and its mother, and to their joint futures.

Ashley — December 23, 2011

"There are also very important differences between maternity care in England and the US, most notably the role of midwives."

Exactly. I've seen at least one large study that found home birth to be *safer* for low-risk pregnancies in the United States. The hospital practices in England are much closer to the home birth practices in the States, and the cesarean rate is significantly lower (10% lower, last I checked), which means you get the best of both worlds: lower rate of unnecessary risky interventions, and proximity to medical equipment and procedures needed in cases of unlikely complications... It also looks like for second births, the intervention/proximity equation shifts to favor home births, even in England.

There's also the issue of hospital-caused infections, which wouldn't be measured by a study like this, as far as I know. That's an additional risk to entering a hospital, and it's a serious one.

It seems to me that, once you take all the other emotional considerations into account, the risk/benefit equation is definitely close enough to mean that government shouldn't be making any policies about this, even if you're in the camp (I am not in this camp) that believes that a fully-formed baby has rights separate from those of their mother *before* leaving the womb.

First births done at home are riskier. « The Prime Directive — December 7, 2012

[...] the first) is much more riskier if done at home. Sociological Images asks the natural question: so what? Legal policies are not made on the basis of risk. Home birth seems safer than letting children ride [...]