Commodification is the process by which something that is not bought and sold becomes bought and sold. At one time, Americans grew, or raised and butchered, much of their own food. Later, meat, grains, and vegetables became commodified. Instead of working in the fields and with their animals, people would “go to work,” earn a new thing called a “wage,” and trade it for meat, grains, and vegetables. With those raw ingredients, they would prepare a meal.

More recently in American history, the very preparation of food has commodified as well. When I go to a restaurant, I am exchanging my wage for the planting, harvesting, processing, delivering, preparing, and disposal/clean up of my meal. In this way, then, more and more components of our daily nutritional intake have become commodified.

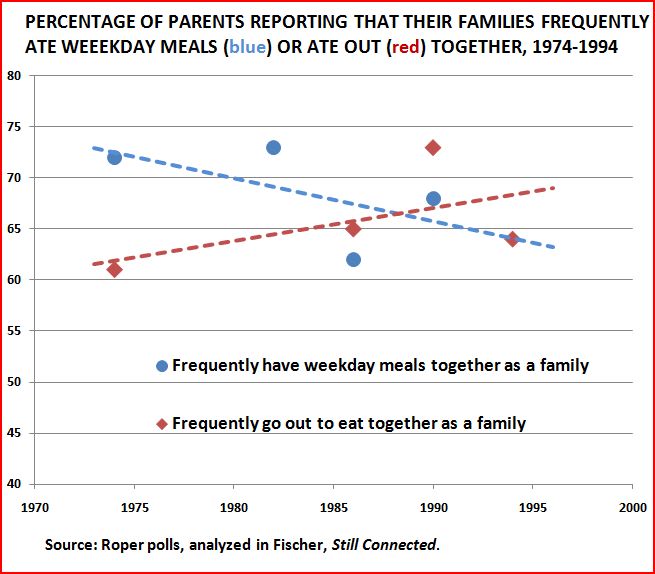

The graph below traces the increasing commodification of “dinner.” When it comes to family dinners, Americans are increasingly turning to restaurants, which commodify the preparation of food and the post-meal chores. Sometime around 1988, the family dinner as a commodity became more common than family dinners at home.

Image borrowed from Claude Fischer’s Made in America.

UPDATE: In the comments, Ludvig von Mises offers this alternative explanation:

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.Another way to look at this would be as a form of increasing wealth. The nobility of old, after all, also did not butcher, harvest, and prepare their own meals, and neither did the wealthiest members of the new rich. Over time, the ability to afford such a thing on a more regular basis has gradually expanded to more and more people.

Matter of fact, there is very little in the way of such luxury that has been enjoyed by the elites of the past that is not available to the majority of workers today. “Commodification” is not, as you suggest, the creation of any kind of new product, but merely of making extremely expensive products affordable to a much larger fraction of the population.

“The characteristic feature of modern capitalism is mass production of goods destined for consumption by the masses.”

Comments 30

citizen — February 8, 2011

Is a line of best fit really a wise representation of a chart with, apparently, four data points for each graph?

Grizzly — February 8, 2011

I don't know that I would agree that "Sometime around 1988, the family dinner as a commodity became more common than family dinners at home." The chart doesn't talk in absolute numbers, but rather uses the term "frequently." Frequently eating out, does not necessarily equate to frequently eating dinner in as a family.

A family that eats out at a restaurant once a week, may consider that frequent, whereas a family that only sits down to a home cooked meal together three times a week may consider that infrequent.

mvd — February 8, 2011

Only four data points over 20 years? What are the statistics on these fits? Where are the error bars on the data points? Can we really draw any conclusions from this?

Xavier — February 8, 2011

Those are some brutal trend lines.

AR — February 8, 2011

Another way to look at this would be as a form of increasing wealth. The nobility of old, after all, also did not butcher, harvest, and prepare their own meals, and neither did the wealthiest members of the new rich. Over time, the ability to afford such a thing on a more regular basis has gradually expanded to more and more people.

Matter of fact, there is very little in the way of such luxury that has been enjoyed by the elites of the past that is not available to the majority of workers today. "Commodification" is not, as you suggest, the creation of any kind of new product, but merely of making extremely expensive products affordable to a much larger fraction of the population.

"The characteristic feature of modern capitalism is mass production of goods destined for consumption by the masses." ~Ludwig von Mises

Datura — February 8, 2011

Wow, that is one of the worst graphs I've ever seen. I don't think anyone should try to draw any conclusions from this.

Jon — February 8, 2011

I agree with others about several points:

-The graph is poorly designed

-The trend lines tend to skew the data. Of 4 data points for each series, one data point could be regarded, based on the graph, as anomalous or as an outlier (~1986 for eating weekday meals and ~1991 for eating meals out).

-There could be some issues with the wording of the question

Ultimately, I think I would need to see a better graph with more data before making a claim that “Sometime around 1988, the family dinner as a commodity become more common than family dinners at home”. And ideally, more recent data (the most recent data on the graph is from 1994!) would be needed to confirm this supposed trend. I wonder if, for example, the recent recession has had an impact on family dining habits.

I just can’t help but think what some of my previous teachers, advisors and bosses would say: “more data are needed”.

tacony palmyra — February 8, 2011

The worst problem with this graph's presentation is that it leads to a misreading, which I think Lisa Wade is falling into. We have no data before 1974. Even if we're concluding that the trend is valid during this time span, don't just extrapolate that trend line back to the beginning of history.

Much social research today focuses on changes observed between the 1950s and the present, and erroneously assumes the mid-century to be a middle ground between the "unnatural" extreme of today and the "natural" state of our origins. I think eating out vs. cooking at home may be a good example of this problem. It makes for a compelling narrative that we want to believe, but I'm not so sure it's true. I have an alternative narrative:

The percentage of the US population who farm today is lower than ever before, surely. But for people who streamed into American cities from the farms (and the immigrants from abroad) at the turn of the last century, they were entering dense urban environments where it was fairly common for people to live in tiny apartments without proper kitchens, with single men eating out at saloons and mess halls every night. In New York City it was trendy to eat out all the time in the 1920s, even amongst the working classes.

The baby boom and move to suburbia in the 50s were accompanied with a new emphasis on family, big new houses with big kitchens where we (and by we I mean wives) would produce fabolous meals for our kids every night. Our newfound affluence was used, not to pay somebody else to make food for us, but to buy new products to do it ourselves. We now had the luxury of restaurant-quality food in the comfort of our own homes!

So when women entered the workforce (again) in the later half of the century, we were left with the McMansion, but the most action our granite counter tops see is holding space for delivered pizza and bags of McDonalds. The kitchen remains a status symbol, unused.

For some lazy research, cherry picking from the Times archives:

"Census Ups and Downs" 1925: http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F10C11FE385D1A728DDDA80A94DE405B858EF1D3

A Census worker mentions it's difficult to find couples at home for dinner because they now eat out all the time

"Wall Street Has Its Office Lunch" 1928: http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F10815F63D5914728FDDAE0894D8415B888EF1D3

Discusses the move toward offices providing their own cafeterias in the building

"Points About Eating Out" 1943: http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=FB0B1FFC3D54107B93CAAB1789D85F478485F9

Mentions all the people who live in rooms who can't cook, in the context of war rationing at restaurants vs. food at home

"Our Incredible City" 1946: http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F40F14FF3D55167A93C0AB1789D95F428485F9

40% of restaurants in NYC are cafeterias -- this was working class food, not just for the posh

"'Eating Out' In Decline: TV, Increase in Children and Less Spending Are Factors'" from 1952: http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F10915FB3B58107A93C4A8178FD85F468585F9

Already in decline in 1952!

"Eating Out -- At Home" 1956: http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=FB0C1FF83A55177B93C7A91789D85F428585F9

Basically the first restaurants offering take-out, trying to survive

^ Granted, half of these are NYC-specific, but I think this is as convincing an idea than the oversimplified argument that we've become more removed from our food as we eat out more vs. eating at home. We moved from the farm to the city to the suburb. We grew our food, then we ate out, then we ate in, now we eat out again (and some of us are moving back to the city again!)

Monika — February 8, 2011

I wonder what this says about the distribution of household chores such as preparing meals and women's participation in the labor market?

David B Traver Adolphus — February 8, 2011

"At one time, Americans grew, or raised and butchered, much of their own food."

That time was the mid-19th Century, at latest. Remember that the great industrial revolution migrations to the cities were well under way during Reconstruction.

I think you're succumbing to the myth of the American agrarian paradise there. The period to which you refer was so very long ago, it's no more relevant than saying, "At one time, Americans lacked indoor plumbing."

Rebekah — February 8, 2011

Does eating at home instill different values and ways someone might go about life, then someone who goes to a restaurant for their meals? What is the importance of preparing it yourself or having someone do it for you? This is what it made me think about while reading it. Will someone get upset because they think eating in a restaurant says something negative about them versus cooking at home and the same about someone cooking at home instead of eating out. What are the implications to both decisions and why do we do the things we do? A very thought provoking post in my opinion.

gre'nichgrendel — February 8, 2011

I just have to say that I learn so much on this site regarding critical thinking when viewing data and charts, etc, from reading the comments. I mean I know a lot of it theoretically, but seeing it applied is really helpful. There are so many great questions that pop up regarding the data itself, how it was gathered, how it can be interpreted, how it's been presented. I feel like I get such an education from both the posts and the commenters! Much more so than any of my courses so far (but then I'm still an undergrad).

Philip Harrover — February 8, 2011

I wonder what this says about the distribution of statistical literacy among social science bloggers.

MissDisco — February 9, 2011

Dunno what is defined as a restaurant, but are there more 'family restaurants' and places to eat out nowadays?

Andrew — February 9, 2011

How do I frame this and stick it on the top?

That's an exceptionally persuasive response.

The original post, admittedly, gave me the giggles. I read it shortly after returning home from a restaurant that opened in 1612 and, unfortunately, never bothered to update the menu. Granted, in 1612, some neighborhoods were ringed with farmland and there were livestock stables and barns on the real estate that chain supermarkets and boutiques now occupy (a particularly trendy area still retains a name that means Barn District). Even so, the tradition of commodifying food (and the separate matter of dining in public) is deeply rooted in times long before the European invasion of America.

I'd add that for any person whose enterprise has ever been something other than subsistence farming, food is fundamentally a commodity by default, which puts the cultural shift to which Lisa refers somewhere around the Bronze Age. And likely earlier; the introduction of currency (or that supposedly "new thing called a 'wage') didn't exactly invent the concept of trading inedible-but-desirable items for food.

Anthropologists where you at!

Anonymous — February 19, 2011

This article gives us an idea that how the wealth or standard of living of the American citizens are growing. This gives a marketer a opportunity to tap new markets and profit from it.

Rahul Gupta — February 19, 2011

This article gives us an idea that how the wealth or standard of living of the American citizens are growing. This gives a marketer a opportunity to tap new markets and profit from it.

SteveA — February 23, 2011

Its humorous that commodification is described as a luxury for elites when nowadays it is something completely normal. I wouldnt say my family is rich but I would say that we go out to dinner once or twice a week. As the article says, its not just the sitting down and eating, its planning the meal, making the meal, then doing the chores after the meal. It could be looked at in comparison to cost opportunity, is spending $60 for a family of 4 worth not having to do all the necessary work to have a substaintial meal? In my opinion, yes I've done it almost every day since I was a freshman.

This Week in Sharing | 3D Printings & Additive Manufacturing — September 7, 2011

[...] families eat dinner together, it's done more and more at restaurants; on the commodification of dinner. [...]