Princeton sociology professor Viviana Zelizer wrote a wonderful succinct editorial for the New York Times about the idea of giving money as a gift. Money, she explains, is used in the most impersonal of transactions (even antagonistic ones, as someone who recently paid a parking ticket recalls), so giving money to loved ones can be seen as crass, tasteless, or thoughtless.

Zelizer explains that cultural elites have been worrying about this since the early 1900s. The solution: “camouflage money inside a traditional gift.” Offering some examples, Zelizer writes:

In the December 1909 Ladies’ Home Journal, for instance, the writer Lou Eleanor Colby said she had found a way to “disguise the money so that it would not seem just like a commercial transaction.” She explained how she had incorporated $10 for her mother into artwork. She inserted dollar bills into two posters; one showed five sad bills not knowing where to go, and the other depicted the happy ending: “five little dollars speeding joyfully” toward her mother’s purse.

Housewives hid gold coins in cookies and boxes of candies; dollar bills could decorate belt-buckles or picture frames. Women boasted when the recipient failed to realize that the actual present was money. Men also disguised the money they gave to their wives as gifts, to distinguish it from their allowances. If you give her a check, The Ladies’ Home Journal advised, “put it in an embroidered purse, or a leather sewing basket or a jewel box which will be a little gift in itself.” The better the disguise, the more successful the gift.

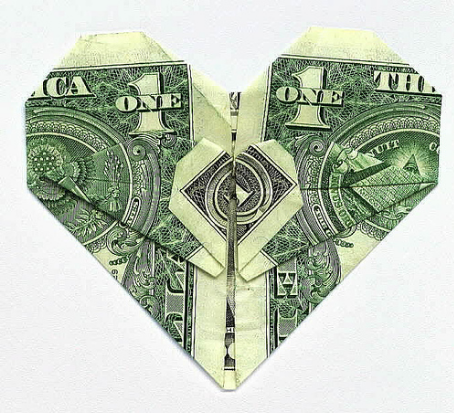

Today these tokens are probably familiar to many of you. One site suggests making the money into a gift basket. Another suggests that you give the gift of (money) origami.

Soon, Zelizer explains, companies figured out how to cash in on this cashing out, inventing the idea of decorated money orders and telegrams:

…in 1910, American Express began advertising money orders as an “acceptable Christmas gift.” Western Union improved on the idea by creating distinctive telegrams for sending money for special occasions, while greeting card companies started selling decorative money holders for birthdays and holidays.

Thus the “money holder” card and the “gift card” was born.

While it may seem obvious to many of us now that gift certificates and money holders exist, Zelizer shows that these objects have a cultural history, devised to solve a particular problem that emerged with the spread of a wage-based economy.

Via Kieran at OrgTheory; photo by Chris Palmer flickr creative commons. Originally posted in 2010.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 45

Shinobi — January 10, 2011

My dad likes to give us cash creatively. He's given it to us in ornaments hidden on the christmas tree, wrapped it in boxes, and stuff like that. By far the best was the year we also go new luggage and my sister and I both got a suitcase filled with crumpled up dollar bills. Nothing says love like a suitcase full of money.

John Yum — January 10, 2011

The "crassness" of giving money as a gift has always seemed odd to me. Having grown up in East Asia, where gifting money is normal and (depending on the holiday) expected sometimes. True, though, these are usually given in a holiday-specific wrapping (red envelopes amongst Chinese during New Year, for example), so one is giving a gift of money, rather than merely money.

The idea that one allows the other person to choose the function of the gift (i.e., "they know how to spend it better") always, too, seemed a better reason for giving a gift than presupposing what another person wants. Sure, if you know that someone wants X, then the purchase of X can well be seen as something that is nice, but if you don't know what a person wants, purchasing a gift for that person is (imo) impersonal (if you buy a generic gift) or crass (if you gift something that you find desirable, presupposing that, "of course, since I find it useful, the other person ought to as well").

p.s., lisa, you forgot the personal cheque (or even traveler's cheque) that is oftentimes slipped into a card.

b — January 10, 2011

This is an interesting history. In addition to some of the economic reasons noted, I think another reason money gifts are seen as problematic in our society is that "it's the thought that counts," but giving someone money doesn't necessarily require any thought about what they would like or value. Disguising it as or hiding it in something else that they would like, on the other hand, shows that even if you didn't put a lot of thought into the gift itself, you put thought into the packaging. And a gift card shows you thought about what they might like to spend their money on.

Personally, I prefer receiving gift cards - I always feel a need to spend cash gifts on something responsible and useful, while gift cards for some reason I have an easier time spending on fun things. And I'm more likely to go window-shop if I feel like it if I have a gift card - if I know (or feel like) I can't buy anything it's less fun, but even if I don't buy anything the knowledge that I could, because of the card, makes it fun to look. So for me, it's a gift both of the items I eventually buy and the fun outings I have because of the gift card's mere presence. I wonder how many other people have this psychological barrier between gift cash and gift cards?

Heather Leila — January 10, 2011

I just posted about the pitfalls of giftcards in December, hoping my family would refrain from giving me gift cards for Christmas. It didn't work. I'm about to leave the country, so that meant I HAD to spend the cards quickly so I wouldn't forget about them or they wouldn't expire during the two years I'll be gone. And what if there isn't anything to buy in the store that I want? I really ended up using the gift cards to buy other people presents.

Here's my post about the many problems with gift cards:

http://heatherleila3.blogspot.com/2010/12/five-pitfalls-of-gift-cards.html

John Yum — January 10, 2011

Pet-peeve phrase: "...and as we all know..."

This phrase implies that if I don't know the subject at hand, don't agree with it, know of evidence to the contrary, etc. then I am (somehow) implicitly uninformed, wrong, a denialist, etc.

As you, lisa, are a sociologist who deals with the topics that are covered on this site, I find it strange that you continue to use such phrasing, even though you know that your site attracts more people than those who might share your cultural background. Since you know that you are writing to a broader audience, it becomes less likely that people reading will ascribe the piece of knowledge you present.

Analogously, if I write, "As we all know, it is customary to give used paper money with odd-numbered serial numbers as a wedding gift," or, "As we all know, it is customary to give money as a New Year gift," then I would argue that I am implicitly dismissing the experiences of people who didn't know these things by implying that they are uninformed.

However, if we are looking at the probability of a piece of knowledge being shared by a global "we", then there would be many things that Americans (I use Americans, since we are the majority of your readers, and we do tend - as a population - to hold one-way cultural expectations of much of the world) would not be likely to know. Taking, for example, my first statement above, this is not likely to be something that would be a piece of majority knowledge to a global "we" (since it is - afaik - a Japanese tradition). However, the second could well include more 1/2 of the global population (population of China, the Koreas, Japan, much of SE Asia, and all their diasporas), making it something that the global "we" could find to be majority knowledge. Still, I forward that even though the latter of the two presented statements is a piece of majority-knowledge to the global "we", it, too, remains implicitly exclusionary if phrased as part of a, "as we all know" statement.

I would suggest (as I do to all my students) that you be very careful with the phrase, "as we all know," especially when dealing with social constructs (since such constructs often never shared globally, or held by a majority of the world's population). Thus, the phrase, "... as we all know..." is becoming less useful in our ever-globalizing world, unless you explicitly define the group that shares the understanding described.

Your site does attract visitors from around the world. True: most of the readers are from the US, but that isn't an excuse to just implicitly exclude the inherent cultural viewpoints opposing or not including the stated, "as we all know," especially when (at a global level), the gifting of money isn't something that is crass or impersonal, especially when one includes the gifting of money within cultural observances.

(Yes, this is me continuing to point out, a pet-peeve though this topic is, when you implicitly or explicitly exclude the social constructions of other parts of the world; appearing to implicitly assume that the US condition is the standard one to which we all ascribe.)

A — January 10, 2011

There're a few more, too. Amazon.com is attempting to patent a system that will automatically convert unwanted gifts to credit, before they are even sent. That, to me, seems like an environmentally-friendly form of giving cash, except the giver doesn't realize they are giving cash. (There is more information on that here: http://technology.newsplurk.com/2010/12/amazon-tech-helps-return-gifts-before.html )

Another one that I personally find unquestionably tacky is the cash wedding registry. It's based on the idea that many newlywed couples now have been living together for a while, and thus they already have most of the things on traditional registries (appliances, cutlery and dishes, etc). What they really need is cash for the mortgage, groceries, health care, etc. So the cash registry allows them to get what they really need (money) rather than more stuff. I guess it makes sense in theory, but something about it just grates on my romantic sensibilities. One registry (SimpleRegistry) even, if I understand it correctly, allows you to register for anything online, and then redeem all gifts as cash. So, although Aunt Mildred might think she's getting you a painting or a picnic, ultimately, she's just giving you cash anyway. But that seems so deceptive that maybe I'm getting the process wrong.

So giving cash as gifts continues to evolve and evolve...

Alex — January 10, 2011

John, have another look at the sentence you're taking issue with:

Money, she explains, and as we all know, is used in the most impersonal of transactions (even antagonistic ones, as someone who recently paid a parking ticket recalls), so giving money to loved ones can be seen as crass, tasteless, or thoughtless.

"As we all know" refers to the phrase "is used in the most impersonal of transactions." Given the nature of money, this is indeed something that is known by everyone who participates in a culture that uses money. I would venture to say that very few people who live exclusively in a non-money-using culture have access to the internet, so this example is a valid use of "as we all know."

April — January 10, 2011

I got money for Christmas in two forms this year:

My parents gave me a gift card to REI. But, to be fair, I'm an REI member and they know I do bicycle touring and camping as a hobby. My parents love to help me out with my bicycle stuff, but they know as well as I do that they don't know how to pick out that kind of stuff. The first year I asked for something bike-related (rain gear!) I got a check, and in the memo line was written "rain gear." So this year, when asked what I wanted, I said, "money for bike stuff." And so: REI gift card. I'm going to buy an inflatable pillow, maybe a summer-weight sleeping bag or travel pump for flat tires. I'll make sure to tell them what I get with the card and thank them again.

My brother gave me origami money in a cute tin. But, he's always love origami, when we were kids I often bought him nice origami paper for Christmas. There was a whole collection of fun things, some of which were even based on silly puns. A heart, a peacock, a frog that jumps...the dollar amount wasn't huge, but it was easily one of my favorite gifts this year, because I didn't just get money: My brother spent *time* on my gift. The downside, of course, is that I haven't spent much of the money because I hate ruining his hard work!

Anonymous — January 10, 2011

I struggle a lot with the money as a gift thing, mostly because I have this notion that the perfect gift is something that the other person wants, but would never buy for themselves; I feel like straight-up cash ends up being used for everyday stuff, gift cards are a little better, but even then- you get someone a gift card to Wal-Mart, they might buy groceries with it. I do LOVE restaurant gift cards, however.

This is all purely subjective, and I do feel a little guilty about it sometimes, I mean, why not give someone cash if they need it? I feel like it *shouldn't* bother me, but it does.

I can't help but wonder if I also have some sort of grudge against all the useful stuff I used to get for Christmas when I was a kid; I guess I just still feel like toothbrushes are something you should have regardless, and that they shouldn't qualify as stocking stuffers. To me, that sort of mundane everyday stuff shouldn't really be a gift unless it's really nice, or for something like a Baby Shower or housewarming, where that's the whole point.

That's just me though. I doubt I'm the only one to feel this way, though you won't see me dispensing advice on it like I'm an expert.

Bagelsan — January 10, 2011

I imagine that this is related to how you're often supposed to "hide" how much something cost -- at least, I've always been taught to remove price tags, etc. before giving someone a gift. When giving cash it's impossible to hide the value, and that can lead to embarrassment with mismatches or people looking cheap (ex. my parents gave my teenage cousin a $50 dollar bill for Xmas... and then I promptly unwrapped a $100 bill from his mom. Whoops.) Maybe hiding the money itself is supposed to say "hey, I tried!" as a polite nod to not telling everyone how much you spent on them.

Graid — January 10, 2011

Interesting points about the stigma of giving money and showing much much a gift cost.

From a personal perspective, I loved getting money as a gift, and it wasn't considered odd to get sent it by relatives when I was growing up (in Scotland.)

Most of my relatives would give me cheques, only the occasional one would give the dreaded gift voucher.

Considering it was only after christmas and birthdays that I ever had the money to choose anything somewhat expensive, I really valued the money as a contribution towards the purchase of one large item.

I get that gift vouchers are supposed to show more thought, but often they felt like they showed considerably LESS thought, in that they involve making assumptions about you based on some general idea of 'what young people like' or worse, no consideration for them at all, like the occasion in which I got a voucher for a supermarket. It's different if it's something personalised, but to me, unless there's that personal component- something about the voucher that is specifically suited to the receiver- a gift voucher is worse. Even more of a token gesture than hiding the money in a purse.

In the days of online shopping, gift cards are ESPECIALLY inconvenient, often as generic as money, but more limiting.

Erica Lovins — January 11, 2011

I think everyone might find this article interesting from Slate.com about giving cash as a wedding gift.

http://www.slate.com/id/2168008/

Brandon Warner — January 11, 2011

We are a cash registry but for the good reasons. For example, if you

change your mind about an item, find it on sale and elsewhere later,

register for non-physical goods or services (think honeymoon, charity,

etc.). Also, a lot of our couples use SimpleRegistry to register for

'local goods' meaning a local artist's painting or photograph,

handmade furniture, etc. Our goal is to make registering as flexible

as possible and all in one place...without being limited to the big

box stores.

Our member surveys tell us that 92% of the 'cash' our couples receive

go to the item specified in their registry. If you'd like to learn

more about our survey and why couples love using us, please let me

know and I'll be happy to send you member testimonials and results.

Happy New Year!

Best Regards,

Brandon Warner

Co-founder

www.simpleregistry.com

Che — January 11, 2011

I remember my grandparents saying this about giving money, and I never understood it. Especially now, as a broke just-out-of-grad-school young adult; when my dad asked me what I wanted for my birthday and Christmas this year, I couldn't really justify asking for anything except money - I wanted to go visit for Christmas, and I have student loans and medical bills and credit card debt, so money was the most thoughtful gift my dad could give me. It did feel kind of crude to ask for money, but I feel uncomfortable asking for anything, so why not be practical?

Speaking of gift cards, I remember my mom giving our 80-something-year-old neighbor supermarket gift cards because she wouldn't hide them back in my mom's wallet when she wasn't looking :P We did the same thing for my grandmother - she would feel bad taking cash as a gift because she though my mom needed it, but she would accept gift cards.

bearmonkey — January 12, 2011

I grew up in an Italian-American family, and also in an area full of Italian-American people. Money was always given openly, both in my family and at birthday parties with other kids. It was perceived to be the best possible gift because you could do what you wanted with it, including save it up for college. So, quite the opposite of crass. It wasn't until I moved out into the world that I discovered people were squeamish about giving money as gifts.

James — December 23, 2013

I've noticed that in my own upbringing, cash / checks are an appropriate gift for children from relatives (uncles, aunts, grandparents, etc) but not from close friends or nuclear family.

There's a distinct sliding scale of thoughtfulness, which seems to be based on how well you're 'supposed' to know someone else. If it's a close friend or family member, the assumption is that you always know what to get them, so money seems crass and/or lazy.

Tara — December 23, 2013

Money is an acceptable, and even expected, gift on certain occasions: graduation, wedding. These share two traits: that of being a transitional time of life in which one is setting up a new life and needs the resources to do so well; and that of being one-directional gift giving occasions.

The first point contrasts to smaller more frequent occasions are more frivolous, and call for more impractical, surprising gifts. Wth regard to the second point, physical gifts are important because they disguise the fact that the whole charade is a simple trade. If I give you a teapot and you give me a hamster, we each go home with something we didn't have before, something to see or use. If I give you $50 and you give me $50, we go home exactly as we came. Furthermore, gifts help disguise imbalances: if I give you $50 and you give me $30, at least one of us is going to feel uncomfortable.

shorelines — December 23, 2013

I prefer to give non-cash gifts because I'm usually pretty successful in spending far less than suggested retail on most things I purchase. For the same reason I love receiving gift cards. The down side of gift cards is that they very often end up being used for necessities like toilet paper, gas, or clothes for the kids rather than something I want for myself.

Hey, Mister, Can You Spare a Thousand? Crowdfunding as the Middle-Class Version of Panhandling | SociologyInFocus — May 5, 2014

[…] on their birthday instead of buying a present. In fact, when given as a gift, money needs to come disguised, so it’s not seen as tacky. When I Googled “manners” and “asking for money,” over 9 […]

Aleodor Costescu — May 21, 2014

What gets my panties in a twist is that someone needs to have a PhD to talk about a non-issue. It's mind boggling. I mean take your PhD and go investigate healthcare issues. Or mental illness in America. Anything. Or if it's a PhD in science, how about study fusion? Nooo, the lady wants to talk about people getting money for their birthdays. I give up.