Does it matter when popular stories about “sex trafficking” are based on half-truths, junk science, and/or religious beliefs? Given that many people are interested in the issue of human trafficking in general and human trafficking in the sex industry in particular, it is critical that we face the consequences of stories told in the name of rescuing girls and women.

Since the passing of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA), stories of human trafficking have been well integrated into the American cultural imagination. While there are now many more reliable scholarly resources on human trafficking today then there were at the turn of the 21st century, many individuals still derive most of their knowledge about human trafficking from sensationalistic media stories about so-called “sex trafficking.” [i]

In the United States, mediated stories of human trafficking of sex workers vary around specific contextual details of who, when, and where, but they consistently portray the same messages about why and how. Hollywood action-adventure characterizations of victims and villains are deployed; complex structural problems are squeezed into personal morality tales; and the stories are then used by anti-sex work politicians and activists to justify heightened forms of criminal punishment. While the stories may have popular appeal, evidence suggests that more criminalization actually hurts all sex workers across the continuum of privilege and oppression.

The argument I will make here is organized around the following interrelated points:

- We must critically interrogate dominant stories told about people in the sex industry. (There are numerous examples, but I will focus here on the content and impact of recent feature length film in particular, The Abduction of Eden);

- Such stories justify the criminal punishment system via rescue/capture methods as an avenue for social justice (this includes laws being proposed right now in Washington State);

- Because the criminal punishment system has a long history of destroying the lives of poor people and people of color — including those of sex workers — academics and activists concerned about people in the sex trade need to rethink this entire set of dominant stories and strategies.

1. Demonizing tales

While there are a plethora of sensationalized media stories about coercion, abuse, and trafficking in the sex industry one recent story – Abduction of Eden (AKA Eden, released 2012) – provides a powerful blend of Hollywood and Biblical tropes. This in combination with the promise that Eden is a “true” story makes it a productive one for understanding the relationship between American cultural storytelling and political policies about sex work and human trafficking.

Eden is a feature length film directed by Seattle filmmaker Megan Griffiths derived from the allegedly true story of Chong Kim. The protagonist (actress Jamie Chung) – a naïve 17 year old girl with hard working, Korean immigrant, Christian parents – is kidnapped and brought to a warehouse/jail with dozens of thin, young, feminine, cisgender, and (mostly white) girls who are forced to stand obediently in line wearing identical white underwear-tanktop sets. The protagonist’s (now renamed “Eden”) first assignment is on a BDSM porn set; she sobs as her hands are handcuffed and pulled upward. At her next job Eden attempts a dramatic escape; bloody and screaming she runs into a suburban backyard with white women drinking white wine (they don’t call the police and Eden is recaptured). We learn that Eden’s best friend in the prison/brothel was stolen at age 13, and when her friend gets pregnant and gives birth, her baby is also stolen and sold. A message portrayed in Eden is that when girls disobey or simply grow too old for the work (20+ years of age) they are executed. The film also implies that this sex trafficking operation is part of an international network directed from outside the US. Although the external controller is never named, there are Russian men working for the operation and Dubai is frequently mentioned. This includes a scene where the drug-addicted supervisor (Vaughn/Matt O’Leary) threatens Svletlana (Naama Kates), a blonde Russian woman with being sent back to Dubai, where she “can get dicked by donkeys all day.”

If these themes are not enough to convince the average American viewer that the world of sex work is pure evil (relying on enslaved cisgender girls enacting forced BDSM porn and probably dictated by an international network of men from Russia and the Middle East who have sex with donkeys), the film hits home the message with multiple Biblical references and metaphors.

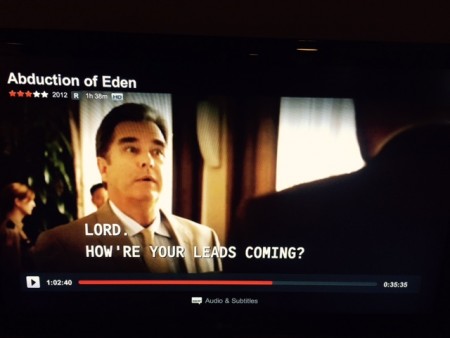

This includes the obvious metaphor about the Garden of Eden. It also includes a scene where God appears in the body of a tall white deputy named Ron Greer (Tony Doupe). When Greer questions the corrupt, murderous federal marshal Bob Gault (Beau Bridges) about his possible role in a double homicide, Gault/Bridges looks upward with fear in his eyes and says: “Lord. How are your leads coming?” When Greer informs him that his cell phone activity was picked up near the scene of the crime, Gault replies: “I’ll be damned.” Greer responds: “Well I surely hope not.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beau_Bridges

What Eden viewers may not be aware of is that there are many counter-narratives to the “truth” claims of such messages. For example:

- While there are certainly degrees of coercion or lack of choice found in all jobs especially unregulated or informal economy labor including the sex industry, the portrayal of a warehouse of dozens of kidnapped teenage girls being forced to be prostitutes is simply not consistent with reliable data about the experiences of contemporary sex workers, especially as practiced in the U.S.

- Individuals representing a spectrum of genders, sexes, races, ages, social classes, sexual orientations, and body types work as sex workers.

- BDSM is a consensual sexual lifestyle choice for many people as is participation in pornography – but both of these activities have long been demonized by conservative feminists and religious groups. The stigma and fear of BDSM and porn can thus be used as an easy tool to invoke shock and horror from people who are morally opposed to both.

- Despite narratives about international “sex trafficking rings,” critical criminologists describe trafficking in the sex industry as better described as “crime that is organized” (rather than “organized crime”).[ii]

- Eden was produced and consumed within a broader U.S. cultural context where fictitious claims about “sex trafficking” are common, ranging from grossly inflated and unreliable global estimates, to debunked claims that the Superbowl creates an uptick in sexual slavery, and statistically untenable assertions that the “average age” of women entering prostitution is 13-14.[iii]

- As it turned out, none of the content of Eden was based in truth. In June of 2014 multiple investigators into Chong Kim’s story found that she lied about the everything.[iv] Kim was investigated and charged for fraud by a variety of anti-trafficking organizations.[v] But Eden still had several years of celebrity adoration before this news broke.

Initial mainstream responses to Eden

Even before its official release, mainstream (non-sex worker and non-allied) audiences and critics went wild over the story of Eden. While many found the performances impressive and the action-adventure storyline gripping, what sealed Eden’s critical success was that people believed that this story was true. Feminist and women’s groups, churches, and film festivals sponsored screenings; awards were given, local anti-sex work/trafficking politicians were featured, people became enraged en masse and were motivated to join the crusade. The text of Eden folded seamlessly into the curriculum of U.S.-based anti-sex trafficking efforts with its images of taped mouths, chained wrists risen toward the heavens, “in our own backyard” and “stolen innocence” messages, and the idea that the average age of sex trafficked girls in the U.S. is age 13. The true story of Eden appeared to be an American anti-sex trafficking activist’s dream come true.

Even mainstream/secular journalists converted to Eden’s cause, infusing their reviews with Judeo-Christian language and imagery. David Schmader of the progressive Seattle based periodical The Stranger called Eden “a miracle.”[vi] James Rocchi of MSN Entertainment described Eden as “a rewarding, righteous example of how fiction can tell the truth.”

Anti-sex work apologists may try to explain away the embarrassment around Eden (as well as other high profile “sex trafficking” stories)[vii] as just an anomaly, or as a few people stretching the truth for a good cause. But Eden is just the visible cultural iceberg of a story that has already become embedded into U.S. policing practices.

2. Context of U.S. policing & criminalizing policies

Part of the reason for the success of Eden is that it was preaching to an American choir that already had the why and the how part of the story in place. It also complemented dominant approaches to end trafficking in the sex industry that feature coercive “law and order” methods where participants are either forced to be rescued/reprogrammed or captured/incarcerated. The rescue side is led predominantly by well-meaning (and mostly white) middle-class women and men (Christians, social workers, feminists) attempting to “save” cisgender girls and women from sex work. The capture side is directed by (predominantly white) men in policing agencies (police, FBI, Homeland Security) who capture girls and women for rescue and men for punishment.

The dynamics between the rescuers/rescued and capturers/captured can also underscore racist power relations. To borrow from Gayatri Spivak’s famous phrase, “white men are saving brown women from brown men”[viii]: Anti-sex trafficking crusaders are often white men and women saving (all cisgender) women from (black and brown) men.

However, we are now in a cultural moment – thanks in part to the Black Lives Matter movement – where many white middle class people are collectively and finally having an epiphany around the reality of police brutality, mass incarceration, and criminalization of everyday life for poor communities and communities of color.[ix] But what many people have not yet made the connection on is how these same principles need to be applied when evaluating the war on trafficking.[x] This war combines many of the same strategies from the “war on drugs” and the “war on terror” (targeting “urban gangs,” people of color and immigrants) to create even more invasive policing and surveillance mechanisms of marginalized people’s everyday lives.

This brings me to the current legislative climate in Washington State: the location where Eden was produced. Washington is currently facing several new state legislature bills intending to create more criminal penalties for clients of sex workers[xi]. The bills are largely generated and coordinated from the desk of Washington State senator Jeanne Kohl-Welles, who is a long time supporter of state level anti-trafficking legislation.

An earlier anti-trafficking bill (also sponsored by Kohl-Welles) resulted in harsh felony punishment for domestic “traffickers” in Washington State. The first individual sentenced under this new law in 2009 was a 19-year-old African American man working as a pimp/manager/boyfriend to a group of young African American women in West Seattle.[xii] He sits now with many other young men of color in prison, many of whom were first incarcerated under the failed and racially discriminatory “war on drugs,” and now also increasingly incarcerated in the name of the war on “sex trafficking.”

With Federal and State punishments now locked in for “traffickers” in Washington State, the new set of proposed state laws are now set on the clients as part of the “end the demand” approach (AKA the “Nordic Model”). The idea is that if men are given harsh enough criminal and social punishments for buying sex, then they will stop trying to buy it. This is a popular idea with contemporary anti-sex work activists despite the fact that:

- there is no reliable empirical evidence to support that this approach is helpful for reducing harms to sex workers,[xiii]

- leading global health experts oppose any form of criminalization in the sex industry due to the health harms it poses for sex workers,[xiv]

- sex worker activists and advocates have consistently documented the harms of criminalization and policing on the well-being and human rights of people in the sex industry,[xv]

- these policies criminalize sexual interactions between consenting adults, and:

- more criminalization ≠ social justice.

Is there a connection between sensationalist “sex trafficking” stories such as Eden and policies that hyper-criminalize the sex industry? I think there is. Not only do these stories serve as a popular master narrative around the sex industry; in this case the critical acclaim for Eden (and its director, Megan Griffiths) is also intertwined with the success of Kohl-Welles’s push for increasingly harsh anti-sex trafficking legislation in Washington State. At a May 2013 screening of Eden, Kohl-Welles was featured as an expert on sex trafficking; Kohl-Welles subsequently supported the Motion Picture Competitiveness Bill in Washington State, which directly benefits filmmakers like Griffiths. In October 2014 Griffiths spoke in support to Kohl-Welles’ re-election.

3. Work with sex workers, not against them

Many progressive individuals and communities aspire to support the war against trafficking, and want to trust that laws that criminalize men actors will help girls and women who are coerced, abused, or trafficked in the sex industry. However, evidence from global health and human rights researchers consistently show that more criminalization hurts all sex workers across the continuum of privilege and oppression.

Because of the harms of criminalization:

- We must insist that the voices of a diverse range of sex workers be included in all panels and policy discussions that impact them.[xvi]

- It is time for class- and race-privileged individuals to examine their own complicity in supporting sensationalistic stories and moralistic rescue/capture policing strategies.

- People concerned about exploitation in the sex industry should join activists working for the labor and human rights of people working in the sex industry. This includes opposition to criminalization of consensual adult sexual exchanges.

- Rather than seek to punish individuals who are already marginalized, and/or punish people for engaging in adult consensual sex, it is time to work with sex workers against systemic punishment, criminalization, and institutional exclusion of women, people of color, poor people, trans* individuals, undocumented people, and homeless youth – many of whom rely on the informal economy including sex work.

If you care about improving the lives of people in the sex trade it is time to advocate for a greater diversity of sex worker stories and perspectives on how to first discuss and then solve coercion and abuse in the sex industry. There may certainly still be space for religious beliefs and metaphors in this wider diversity of stories and plot lines. However, if one truly listens to the bottom line perspectives of sex workers around the world, it will become clear that we need to look beyond the criminal punishment system for solving social justice issues.

————

References and further readings:

This essay is an extension of an argument that I made in an earlier publication, which was featured as a dialogue/debate amongst experts on human trafficking: Lerum, K. 2014 (Winter). “Human Wrongs vs. Human Rights.” Contexts.

- [i] Many individuals advocating for sex worker rights, myself included, object to the term “sex trafficking” arguing that the term prioritizes moralistic, limited, and objectifying notions of the product (“sex”) rather than on the people producing that labor (sex workers). Many sex workers’ advocates thus argue for a different way of talking about the issue: e.g. “human trafficking of sex workers” (not “sex” trafficking). Just as people refer to “human trafficking of agricultural workers” (not “food” trafficking) and “human trafficking of domestic workers” (not “house” trafficking).

[ii] See: M Segrave, S Milivojevic, et al., Sex Trafficking: International context and response, Willan Publishing, Devon, UK, 2009, pp. 9—10.

[iii]http://traffickingroundtable.org/2011/01/fact-or-fiction-what-do-we-really-know-about-human-trafficking/

[iv] http://reason.com/blog/2014/06/12/eden-sex-trafficking-fable-falls-apart - [v] http://slog.thestranger.com/slog/archives/2014/06/04/chong-kim-the-woman-whose-allegedly-true-story-served-as-the-basis-for-megan-griffiths-film-eden-revealed-to-be-a-fraud

- [vi] http://www.thestranger.com/seattle/real-world-horror-film-world-triumph/Content?oid=16638121

- [vii] Two recent examples include the controversy around Somaly Mam http://www.newsweek.com/2014/05/30/somaly-mam-holy-saint-and-sinner-sex-trafficking-251642.html , and the Hollywood film, Taken, starring Liam Neeson http://bitchmagazine.org/article/trade-secrets

[viii] Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. 1993. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader, eds. Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester, p. 93.

[ix] Texts such as Michelle Alexander’s (2011) The New Jim Crow have also been helpful for filling in many white middle class people’s consciousness around how the “war on drugs” not only completely failed to reduce drug abuse but in the process also demolished the lives of millions of people of color who were imprisoned for non-violent offenses. - [x] In contrast, those who have made this connection are social justice activists coming directly out of communities of color, sex worker, and immigrant, undocumented, poor, and queer and trans* communities. E.g, see Queer (in) Justice (2011) by Mogul, Ritchie, and Whitlock.

[xi] http://swop-seattle.org/resources/summery-of-proposed-end-demand-bills/ - [xii] http://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/teenage-pimp-convicted-of-human-trafficking/?cmpid=2308

- [xiii] http://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/teenage-pimp-convicted-of-human-trafficking/?cmpid=2308

- [xiv] http://www.thelancet.com/series/HIV-and-sex-workers

- [xv] See, for example: A Crago, Our Lives Matter: Sex workers unite for health and rights, Open Society Institute, 2008, http://www.soros.org/ initiatives/health/focus/sharp/articles_publications/publications/

ourlivesmatter_20080724/Our%20Lives%20Matter%20%20Sex%20Workers%20Unite%20for%20Health%20and%20Rights.pdf;

See also: J Huckerby, ‘United States of America’ in Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (ed.) Collateral Damage: The impact of anti-trafficking measures on human rights around the world, GAATW, 2007, p. 231, http://www.gaatw.org.;

See also: Sex Workers Project, Use of Raids to Fight Trafficking in Persons, SWP, 2009, http://www.urbanjustice.org/pdf/publications/Kicking_Down_The_Door_Exec_Sum.pdf. - [xvi] Thus far in Washington State, members of the Sex Worker Outreach Projects (SWOP)-Seattle have been either locked out of – or have had to force themselves into – the recent End the Demand policy discussions. See: http://www.thestranger.com/news/feature/2015/02/11/21689047/meet-the-sex-workers-who-lawmakers-dont-believe-exist

cohabitation”

cohabitation”

Dr. Phil was one of the first to discuss this on a national stage with a show in April 2009 called, “Scary Trends: Is your Child at Risk?” In the video promo for the show, Dr. Phil warns in his classic fatherly drawl: “There are some dangerous trends popping up in schools everywhere, and you may not even know if your children are getting involved.”

Dr. Phil was one of the first to discuss this on a national stage with a show in April 2009 called, “Scary Trends: Is your Child at Risk?” In the video promo for the show, Dr. Phil warns in his classic fatherly drawl: “There are some dangerous trends popping up in schools everywhere, and you may not even know if your children are getting involved.” sent a nude photo of herself to her boyfriend, and in retaliation when they broke up the boyfriend sent the photo to a group of younger girls. The younger girls ran with the photo, using it as a powerful social shaming tool (which of course can only work within a social context where girls’ sexuality is shameful). In an interview with

sent a nude photo of herself to her boyfriend, and in retaliation when they broke up the boyfriend sent the photo to a group of younger girls. The younger girls ran with the photo, using it as a powerful social shaming tool (which of course can only work within a social context where girls’ sexuality is shameful). In an interview with  sent a topless photo of herself to a boy crush. The boy showed the photo to a friend, who embraced the opportunity to gain social power by sharing it widely with kids in that school and neighboring schools. The following comes from a story about Hope on

sent a topless photo of herself to a boy crush. The boy showed the photo to a friend, who embraced the opportunity to gain social power by sharing it widely with kids in that school and neighboring schools. The following comes from a story about Hope on  The Transgender Day of Remembrance was initially a response to the murder of Rita Hester, which occurred 11 yrs ago this week (Nov. 28, 1998). Rita’s murder occurred just 5 weeks after the murder of

The Transgender Day of Remembrance was initially a response to the murder of Rita Hester, which occurred 11 yrs ago this week (Nov. 28, 1998). Rita’s murder occurred just 5 weeks after the murder of  Please see below for a marvelous article on the meaning of today’s events from Jos, a trans identified author writing for

Please see below for a marvelous article on the meaning of today’s events from Jos, a trans identified author writing for