As the Presidential campaign heats up (what you think it’s hot now?) the rhetoric about the “War on Women” will continue to escalate. Even though the GOP will continue to replay Hilary Rosen’s unfortunate “Ann Romney has never worked a day in her life,” quote, we need to refocus on what I believe Rosen was trying to focus on. The fact is that Ann Romney has never had to worry if her paycheck would stretch to the next payday, if she would get assigned enough hours at work or if taking a day off from work would result in being fired. Those are the issues I would hope we focus on as the United States decides who will lead them for the next four years.

Back in the lab, mothers in science have similar issues to contend with.

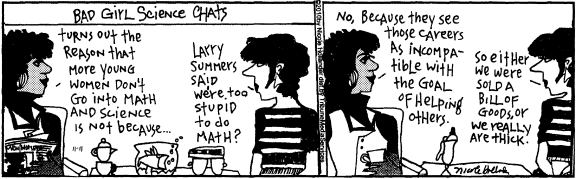

In the recent issue of “American Scientist” the married social scientist couple of Williams and Ceci offer up the theory that perhaps the reason why there are so few women in science and engineering is that women want babies. BABIES! Oh, those cute, plump little beings that bring women’s work to a standstill (well except for changing diapers, feeding, clothing, rocking to sleep, but that’s not work, work, right?).

The premise Williams and Ceci present is that most, if not all, institutional discrimination has been dealt with. Let’s go with that for the sake of non-argument, ok? Their hypothesis is that “the hurdles women face often stem from a combination of several factors, including the decision to have children and cultural norms that place the burden of raising children and managing households disproportionately on women.”

My first reaction (besides laughing, but I said let’s assume no other discrimination is taking place, right?) is that change does not happen this quickly. Even if we could say that equity had found its way to how women in science and engineering operate (fair shake in the grant, publishing and tenure processes) in the last ten years (to be generous), how quickly do we believe it will take to get a change in the landscape? Do Williams and Ceci believe that once the equity horn was sounded that women would hightail it out of the lab into the bedroom to start reproducing? That women who fled to other careers would run begging to be let back into their abandoned labs? Let’s give it a generation before we focus in on just motherhood as the root cause.

On the other hand, let’s go with Williams and Ceci. Let’s say that everything is hunky-dory except the whole mommy thing.

Let’s deal with why the mommy thing becomes the biggest challenge…

Sue Rosser recalls her own challenges with being pregnant and in graduate school. How people immediately expected less of her despite any decline in her work. She even reports that an adviser suggested that she have an abortion because her second pregnancy would interrupt data collection.

Although the National Institutes of Health offers eight weeks of paid leave to postdoctoral fellows who receive the National Research Service Award, recipients can only take the leave in the unlikely situation where every postdoc at the university is also eligible for eight weeks of paid leave. A study conducted by Mary Ann Mason of the University of California at Berkeley documented that of the 61 members of the Association of American Universities (the top elite research institutions), only 23 percent guaranteed a minimum of six weeks paid leave for postdocs and only 13 percent promised the same to graduate students.

Academic science is not your typical workplace. Experiments do need to continue, but much like a law firm, there are other bodies in the lab that can carry on the work. We just need a system that supports this model of respecting that scientists are human beings and as such we get pregnant, have babies, get sick and have to take care of our families.

Rosser ends her piece with some amazing advice for women and men who want to combine parenthood with a career in academic science. The one I repeat over and over to my students is PICK YOUR LIFE PARTNER CAREFULLY! This continues to be the biggest choice women have to make. Will your partner understand when you have to stay late to make sure an experiment doesn’t explode? That you do need a month on the open sea collecting fish? Or need to travel to Africa like Rosser?

In many ways, I wish that Williams and Cece were correct. That the question of why women aren’t staying in science is all about babies. Because we can fix that. We can build child care centers, we can pay women to stay home in order to heal from the birthing experience and bond with their bundles of joy. Sadly, I think it’s not the only reason. But maybe we need to start acting as if it is the reason and start changing the structure of how science is done. Because in the words of Ann Romney, we need to respect the choices women make and, for me, that means having institutions created that support women in those choices. Because it’s not much of a choice if there isn’t a way to act out that choice, now is there?