Gw/P welcomes Holly Grigg-Spall, a features journalist who writes for feminist blogs and whose work on the birth control pill has been cited in mainstream newspapers in the U.S. and U.K.

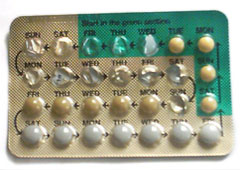

How many of us read the inserts included in a packet of pills? How many decide not to take the pills on the basis of the information enclosed? The rapidly reeled-off list of side effects stated at the end of a televised advert for a new drug has more comedic value than serious consequence to most. If we do have doubts, many of us will rely on the reassurance of a doctor, and then take the pill anyway.

I recently wrote a piece for Ms. Magazine Blog outlining the FDA reappraisal of top-selling oral contraceptives Yaz and Yasmin. It was discovered that drugs such as these containing drospirenone held a significantly higher risk of causing blood clots. Research by the FDA and other bodies suggested this conclusion was definite, while research funded by the pharmaceutical company behind these billion-dollar products, Bayer, suggested the opposite conclusion to be true: that there was no increased risk evident. A team of experts, some of which had financial ties to the company, voted against having the pills taken off the market when presented with the question of whether the risks of taking these pills outweighed the benefits.

Bayer is facing 11,300 lawsuits from women who have been seriously injured and family members of women who have died after taking one of the company’s bestselling hormonal contraceptives. They have settled the first 500 addressed with a total of $110 million in payouts. When discussing this process with a lawyer representing many of the women I was told that Bayer would do anything to avoid a trial wherein the full spectrum of their marketing strategies would be revealed.

The FDA came to the decision to add into the insert included with these drugs a statement of the discovery of “conflicting” research that suggested the pills had a higher risk of causing blood clots (up to three times higher) – acknowledging the discrepancy of the research funded by Bayer and giving it equal standing as that performed by other bodies including the FDA itself.

Prior to this decision being announced a number of women’s health groups got together to write a letter to the FDA asking that they look again at the question put to the board of experts. They argued that the correct comparison for the board to consider would be between drospirenone-containing contraceptives and other oral contraceptives, and not between Bayer’s drugs and unwanted pregnancy. In the final sentence, they remarked that they believed that “lives will be saved” if the pills were no longer on the market. They met with the FDA and one representative asked that the FDA strongly reassess its acceptance of Bayer-funded research. Another asked that the drugs no longer be prescribed and that the FDA “get back to the arc of history and progress that protects women while supporting their contraceptive needs.”

The new labeling will state the “conflicting” findings and advise that women speak to their doctor if concerned. The official statement on this decision, relayed through the media coverage, reminded women that when compared to pregnancy the risk of development of a blood clot was insignificant. They also asked that women currently taking the drugs not stop doing so. Despite the FDA studies suggesting the blood clot risk is particularly high for women under 30, the statement compounded the understanding that the issue is only relevant to those over 35, those overweight, those that smoke, and those with relevant medical history.

Is this additional text in an insert enough? Cynthia Pearson of the National Women’s Health Network has given an unqualified no as her response to the decision. If no is the answer, then what needs to happen next? At this time I’ve seen no coverage outside of news reports that has shown the response of the wider feminist, or just female, community.

When I heard that the FDA was asking for a comparison between pregnancy risks and the risks of Yaz and Yasmin, and that the women’s health groups were calling for, in their letter to the FDA, a comparison between these oral contraceptives and other brands not containing drospirenone, I immediately wanted to know why the comparison was not between using these pills and not using them — as in using other forms of non-hormonal contraception with similar effectiveness. This would produce the biggest gap, and put the statistics in starker relief.

There is too much dependent on the FDA not acknowledging the efficacy of non-hormonal contraceptives or admitting that research funded by the pharmaceutical company producing the drug is not reliable. These were for some years the most popular oral contraceptives. It is important that it is believed that there truly is an “arc of history and progress that protects women.”

Even the women’s health group representatives appear to understand this as a blip in an other uninterrupted history of outstanding service. To my mind, such behavior by the FDA should raise some serious suspicions of their motivating force. They advise that women should discuss this with their doctors – doctors who probably know less than I do, due to time constraints, inclination, as well as doctors that could well be directly or indirectly benefitting from backing Bayer.

If it’s taken this long to get a tentative admission of the blood clot risk, what do we not know about the other side effects of these pills? What were the benefits, outside of preventing pregnancy, of Yaz and Yasmin that the FDA saw as so important to women?

The reaction of the women’s health groups suggests an attempt to work within the system, rather than against it. Does the FDA see itself as protecting the freedom of the millions of women who decided to take Bayer’s oral contraceptives, the millions that made it a bestseller? When a corporation can and will do anything to sell its product in ways that even the most cynical consumer would find shocking can we uphold the notion of informed consent?

We live in a very different time to 1970 when the result of the Nelson Pill Hearings was the inclusion of an insert in birth control pill packets. Then, the other noise of advertising – both overt and hidden – was not loud enough to drown out the message. We are now far happier with corporations telling us what to do than we are with being dictated to by the government. Consumer-driven choice keeps women on the pill – with doctors swapping them between the many brands as side effects appear. Laura Wershler and I put together a guide to a birth control rebellion. We live with a culture that stresses there is no alternative – to the pill or the system that supports it.

To quote a recent New Yorker piece by Margaret Talbot, by the way of Karl Marx, perhaps we must admit that – “Women make their own circumstances but not under circumstances of their own making” – and work from there.

This guest post is was originally published in re: Cycling and is posted here with the author’s permission.