Earlier this month I wrote about gender, debt, and college drop out rates–men’s and women’s different debt tolerance (women have more) is related to their early job market prospects (men have more) and helps explain why men drop out of college more.

Earlier this month I wrote about gender, debt, and college drop out rates–men’s and women’s different debt tolerance (women have more) is related to their early job market prospects (men have more) and helps explain why men drop out of college more.

Now, here’s a new piece of the gender gap in education puzzle. According to a new briefing report presented to the Council on Contemporary Families, “the most important predictor of boys’ achievement is the extent to which the school culture expects, values, and rewards academic effort.” Sociologists Claudia Buchmann (Ohio State) and Thomas DiPrete (Columbia University) present their in-depth findings on the much-debated reasons why women outstrip men in education—also the subject of their new book—in “The Rise of Women: The Growing Gender Gap in Education and What it Means for American Schools.” The full CCF briefing report is available here.

When did the gender gap begin? Some of the gender gap in schooling is new and some is not. For about 100 years, the authors explain, girls have been making better grades than boys. But only since the 1970s have women been catching up to—and surpassing—men in terms of graduation rates from college and graduate school. The authors report, “Back in 1960, more than twice as many men as women between the ages of 26-28 were college graduates. Between 1970 and 2010, men’s rate of B.A. completion grew by just 7 percent, rising from 20 to 27 percent in those 40 years. In contrast, women’s rates almost tripled, rising from 14 percent to 36 percent.”

Is the gender gap translating into wages? “The rise of women in the educational realm has not wiped out the gender wage gap — women with a college degree continue to earn less on average than men with a college degree.” But because more women are getting college degrees, growing numbers of women are earning more than their less-educated men age-mates, and the gender wage gap has narrowed considerably.” But, report the authors, if men were keeping up with women in terms of education, men would on average be earning four percent more than they do now, and their unemployment rate would be one-half percentage point lower.

What should schools do? The authors debunk the notion that boys’ under-performance in school is caused by a “feminized” learning environment that needs to be made more boy-friendly. Making curriculum, teachers, or classroom more “masculine” is not the answer, they show. In fact, boys do better in school in classrooms that have more girls and that emphasize extracurricular activities such as music and art as well as holding both girls and boys to high academic standards. But boys do need to learn how much today’s economy rewards academic achievement rather than traditionally masculine blue-collar work.

Please read here to read more about the gender gap in educational achievement and the sources of it.

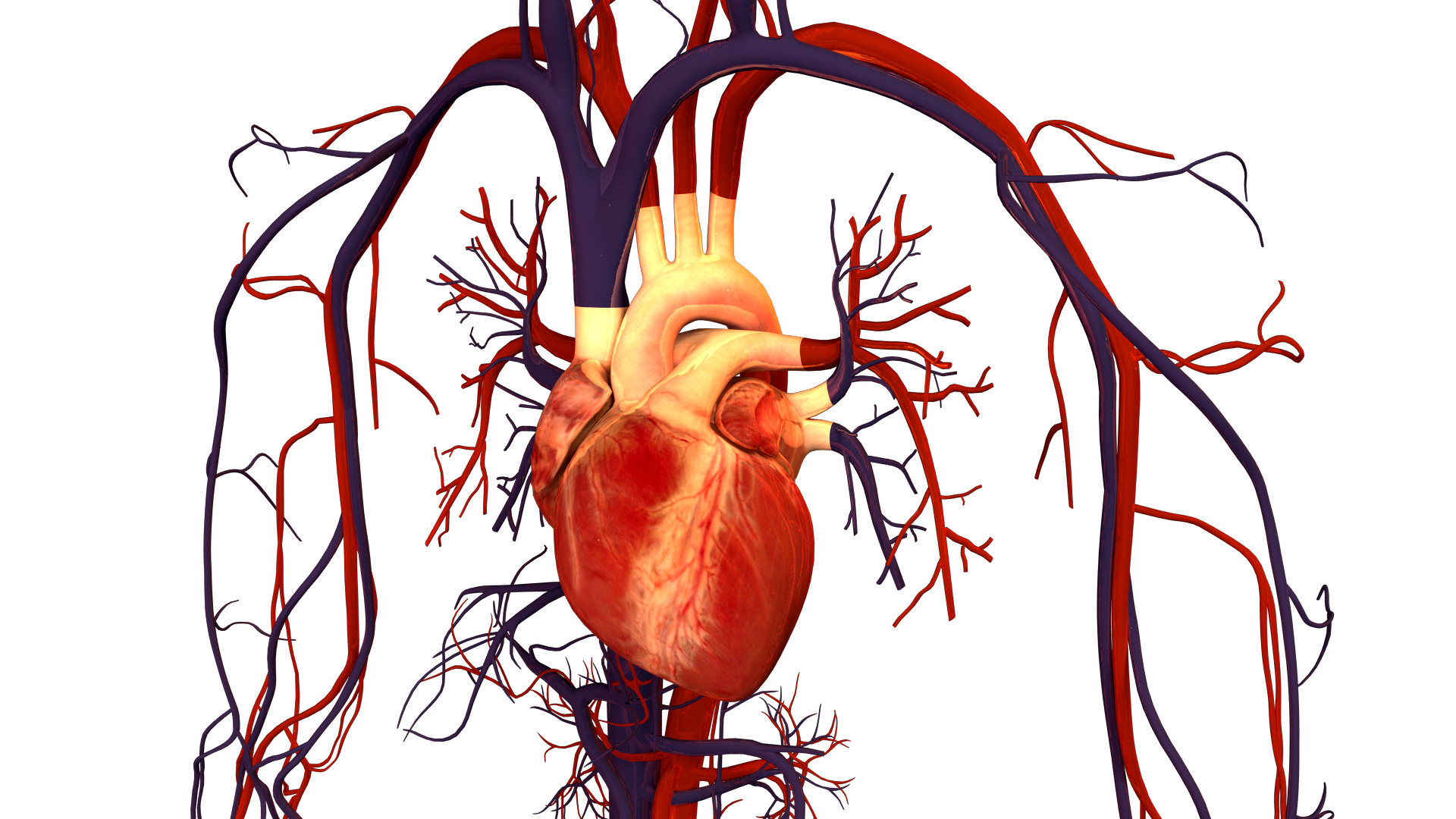

As a women’s health researcher, I am concerned about how long it is taking to bring attention and resources to this problem. After all, it has been decades since we’ve learned that cardiovascular disease affects women every bit as much–or even more–than it does men. Indeed, since 1984, cardiovascular disease has killed

As a women’s health researcher, I am concerned about how long it is taking to bring attention and resources to this problem. After all, it has been decades since we’ve learned that cardiovascular disease affects women every bit as much–or even more–than it does men. Indeed, since 1984, cardiovascular disease has killed  In celebration of International Women’s Day, UN Women has released an English-language song, “

In celebration of International Women’s Day, UN Women has released an English-language song, “ Yesterday in the New York Times, Tamar Lewin reported on

Yesterday in the New York Times, Tamar Lewin reported on  Christine Gallagher Kearney is a Public Voices Fellow with

Christine Gallagher Kearney is a Public Voices Fellow with