This is the first half of a two-post series on the pro-feminist and activist Chris Norton at Feminist Reflections by Michael A. Messner. The second half of “Learning from Chris Norton over three decades” will be published on May 21, 2015 @ 9:00am EST (and linked here).

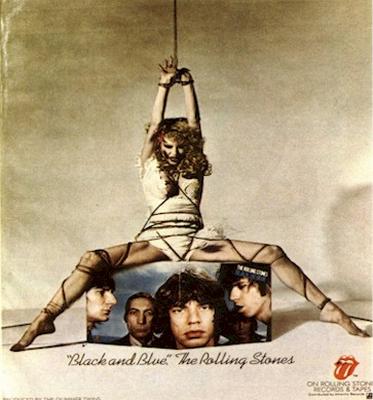

The guy at the front of the room was saying stuff I’d never heard a man say before, especially to a room full of young college guys. Through my basketball-player-eyes, I sized him up to be at least 6’5” with the broad shoulders of a power forward. He had medium-length reddish hair and a ruddy face dominated by a bristly mustache that left his mouth a bit of mystery. And what words emerged from this mouth! With a style that seemed simultaneously gentle and passionate, he urged these young guys to think critically about their own relationship to pornography.  Backed up with a slideshow that depicted popular album covers (The misogynist public billboard promoting The Rolling Stones’ album Black and Blue was one of them), he pointed to the links between sexual objectification of women, men’s use of pornography, and men’s violence against women.

Backed up with a slideshow that depicted popular album covers (The misogynist public billboard promoting The Rolling Stones’ album Black and Blue was one of them), he pointed to the links between sexual objectification of women, men’s use of pornography, and men’s violence against women.

This stuff was hard to hear for young men—and I include myself in this. It was 1980. I was 28 and in recent years had come to define myself as a “pro-feminist man.” I’d even been in a men’s consciousness-raising group in Santa Cruz. But like many younger men like me who were awakening to feminism, I was still struggling with my own deeply engrained erotic attachments to conventional sexualized imagery of women, as depicted not only in Playboy and Penthouse, but pretty much everywhere around me. So here was this giant guy standing up there, calling us out—calling me out—on my shit. What struck me most, and what made it possible to hear what he was saying, was how he spoke as one of us—self-reflexively talking about his own immersion in a culture of eroticized sexism and violence against women, how it affected and continued to affect him. He revealed that he was part of a group of men, Men Against Sexist Violence (MASV), that did educational work on sexism with boys and men—in schools, on the radio, in prisons—while also supporting each other to become pro-feminist men. (As I watched him in action, the punster in me wondered with a private chuckle whether the other members of his group were so, well, massive.)

I agreed with everything this guy said in his presentation and I admired his courage. I wanted to talk with him, maybe become friends with him, and for sure I wanted to interview him for my new research project for grad school—in-depth interviews with men in pro-feminist men’s groups. After the talk, I introduced myself. He greeted me warmly and immediately agreed to allow me to interview him.

Chris Norton was his name, and it turned out he was a guy of middle class origin who had moved to Berkeley in recent years, taken up work as a carpenter while also immersing himself in the progressive politics of the time. I had initially imagined he might become a basketball buddy, but we were only two minutes into our interview before he assuaged me of that illusion. When I asked him about his boyhood relationship to masculinity, he said,

…in sports, I didn’t feel like being aggressive often times and for instance I’m tall and was supposed to be good at basketball, to stand under the hoop and get all the rebounds, and it just didn’t work out—and people’d get pissed off at me for not getting all the rebounds—and then we wouldn’t end up winning and I’d get resentment back, and frustration from people, because I wasn’t doing what I was expected to do and then I’d feel bad about myself and think, “Well I guess I’m a failure, I’m not strong enough or not aggressive enough, maybe there’s something wrong with me or wrong with my masculinity; I’m not a man.”

My 1980 interview with Chris Norton not only helped me to complete a study toward the goal of getting my Ph.D. It also helped to me begin to clarify the sort of person I am. Over the years, I’ve enjoyed thinking of myself variously as a socialist, a radical, a feminist, a progressive, an advocate for social justice. But mostly I don’t do much with these political commitments. Oh, I’ve marched in a few protests and paid dues in some progressive organizations, but I can’t stomach meetings and I hate the grind of building and sustaining organizations. I live so much inside my own head; I read, I write, and the most public thing I do is to lecture and occasionally write an op-ed on some social issue. But this guy, Chris Norton, though he had nearly identical politics as mine, was an opposite character type, a type I admired, even romanticized—a doer, a man committed to acting in the world rather than sitting around thinking about things.

In our interview, Chris spoke of the tensions of being a pro-feminist man, of struggling with how to integrate his commitments to feminism with his daily life as a carpenter, where he worked with men who didn’t always share those commitments. He spoke of MASV’s internal discussions of sexism and pornography, and of his own complicated relationship to feminism and other progressive politics. When I asked him if he called himself a feminist, his response revealed his ongoing self-criticism at his own internalized sexism, while also telegraphing what would become his next major political commitment:

I used to; I don’t know if I do right now. Just because I think I’ve been seeing a lot of limitations to feminism or some of the lacks that it has as far as dealing with class and other things… Some feminists, a certain branch of middle class feminists are sort of like “I want more of the pie” and as someone who’s real interested in changing class relationships and in a more thorough-going revolution I don’t really want to identify with that and I don’t feel real supportive of women executives and women in those positions… In my experience in Latin America, seeing the need to deal with class relationships—I see that as a real difference. The starting point of feminist consciousness between the U.S. and Latin America is really different. I think that any kind of revolutionary movement in the US has to pay a lot of attention to women’s issues, just because that’s where we are. But I think there’s like a bourgeois women’s movement that’s really self-centered and on some level I don’t think I’d call myself a feminist—I think I feel guilty about using that term when I have so much (This whole thing about looks)—I feel guilty because I have so much of this stuff that feels unresolved in myself—It’d be dishonest to call myself a feminist.

It’s two different things. On one level I have objections to some of the tendencies that feminism has and on the other hand I don’t think I’m good enough to call myself a feminist. When we were in the radio collective we called ourselves “pro-feminists,” [which] means that you’re supporting feminism, but not being women, we couldn’t be feminists.

Chris continued working with MASV for the next couple of years, but was shifting his attentions to Latin American solidarity work. I got together with him—maybe around 1983 or 1984 or so—and he told me he was planning to go to El Salvador to work as a freelance journalist, covering the brutal U.S. war that was attempting to suppress a popular uprising. At the time, following the 1979 Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua, there was good reason to believe in the possibility of a succession of victorious liberation movements in Latin America. It was the mid-80s now, and Chris wanted to be a part of this history. He told me he dreamed of being in San Salvador when the victorious FMLA marched in.

I wanted to help—to support Chris, to contribute to the revolution—but of course I’d not stray too far from the local comfort of my oak desk, the very same one upon which I now rest my hands as I write, more than three decades later. I organized a big launch party for Chris at my rambling old rented house in the flatlands of Berkeley. The idea was to gather Chris’s friends and political comrades, as well as some of my own, for a fund-raiser to help Chris get to El Salvador and begin his work as a freelance writer. We cooked up industrial-sized vats of spaghetti for the event, and Chris presented an inspiring El Salvador slide show that outlined the political struggles and stakes. As it turned out, Chris and I had lots of friends; the house was packed to the gills with supporters. And, as it turned out, Chris and I had very few friends who had any money. The pittance we raised may have paid for Chris’s first handful of notebooks.

But he got there. During the latter half of the 1980s, Chris wrote from San Salvador, freelancing for the Christian Science Monitor and other magazines and papers. When I would see Chris’s byline in the CSM I would smile and shake my head in admiration. During those years, still glued to my desk, I wrote my dissertation, prepared articles for academic journals that would hopefully secure me a job, and started my salaried faculty job at USC. Oh, I attended anti-Reagan demonstrations in the early 80s, protested U.S. interventions, donated tiny amounts of money to Latin American solidarity and other progressive organizations—but never did I put my body on the line in the way that Chris Norton did. My admiration for Chris grew… but somewhere starting in the early 1990s, I lost track of him. Immersed in my academic career, building a family in L.A. with Pierrette and our young sons Miles and Sasha, Chris’s life and mine headed in different sorts of directions. I’d think of Chris occasionally, wondering what he was up to.

…

Part II will be posted on May 21st, 2015 at 9:00am EST and linked here.

_____________________________

Michael A. Messner is professor of sociology and gender studies at the University of Southern California, and author (with Max Greenberg and Tal Peretz) of Some Men: Feminist Allies and the Movement to End Violence Against Women (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Michael A. Messner is professor of sociology and gender studies at the University of Southern California, and author (with Max Greenberg and Tal Peretz) of Some Men: Feminist Allies and the Movement to End Violence Against Women (Oxford University Press, 2015).