By Georgiana Bostean and Leah Ruppanner

We face a care crisis in the United States—the older adult population is growing rapidly, yet systems to provide care for them are inadequate, relying largely on informal, unpaid care. The U.S. population ages 65 and over is projected to double in the next 25 years, creating unprecedented need for caregivers as the largest cohort ever, the baby boomers, enters old age. If you live in the United States and have aging parents, chances are good you will be tasked with caring for them in their later years, especially if you are a woman or member of a racial/ethnic minority group. Who steps in to be a caregiver, and the implications of caregiving, are important social, political, and ethical questions. How will we meet the care needs of older adults? And what are the costs of caregiving to the family members with aging relatives?

Taking care of aging relatives has its rewards and its challenges. It can provide a sense of meaning and improve social relationships. But it can also be stressful and have health-harming effects, impairing immune function and accelerating immune system aging. And it turns out that the benefits and harms to caregivers depend partly on the social context in which the caregiving takes place.

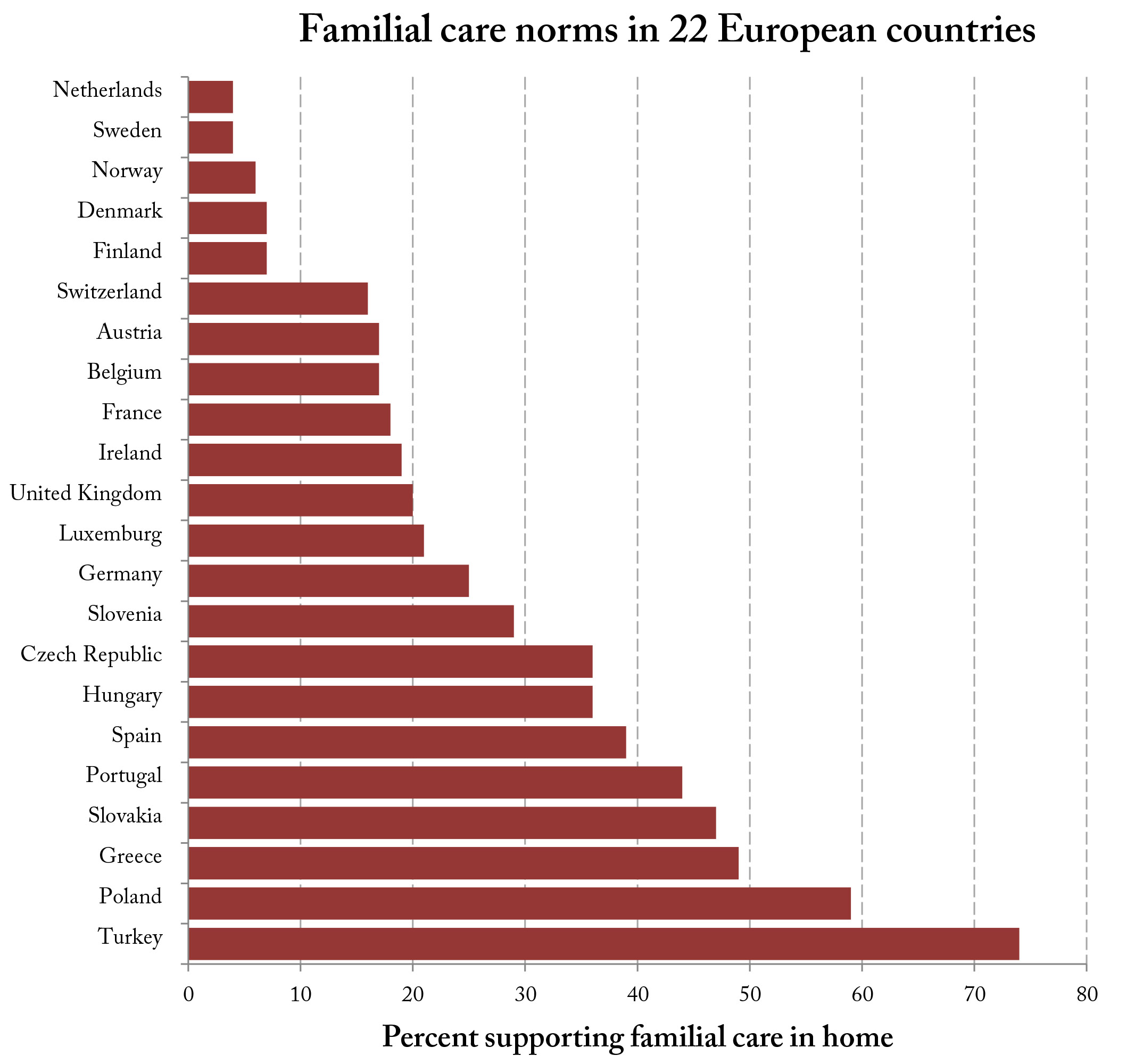

To help figure out how caregivers are affected in different social contexts, we studied 22 European countries to assess whether those in countries with greater societal pressure for informal family caregiving – in the form of strong social norms for familial care or limited public transfers for old age programs – have lower well-being than caregivers in countries with weaker familial care norms and more old age public transfers. We found that strong norms in favor of caregiving at home — and less government support for elder care — are associated with increased harms for female caregivers.

Sociologists often point out how macro-level forces (such as social norms) affect individual outcomes. Our recent research, just published in European Sociological Review, sought to understand how two features of different countries — social norms surrounding caregiving, and public funding for old age programs — are associated with individual caregivers’ well-being.

In the United States, how to provide care for aging family members is largely an individual decision, but social norms and public policies exert powerful influence on individuals’ ideals and ability to act on and carry out those ideals. Caregiving work has historically fallen to women and minorities, reflecting a system of “coerced care,” as Evelyn Nakano-Glenn calls it. Caregivers are not literally forced into their family roles. Rather, certain population groups experience social pressure through norms, and lack of institutional support.

Research suggests that when people are expected to do something based on their social status, but they do not have the resources to fulfill those expectations, they experience health-harming role strain. Caregiving, therefore, may be most deleterious to health when individuals are expectedto provide care, but lack the resources to do so effectively. In such contexts, when alternate options are unavailable, women particularly may step into caregiving roles and suffer health consequences as a result. Many studies find that caregiving affects women more than men; for example, caregiving daughters report greater depression while caregiving sons do not. Thus, coerced care can harm caregivers’ well-being, particularly for women.

In our study of 22 countries, we found substantial variation in people’s attitudes about whether care for aging parents should be provided by adult children in-home. Support for familial care ranged from 4% in Sweden and the Netherlands, to 59% in Poland, and 74% in Turkey.

So, do country differences in familial care norms impact individual well-being?

Our results surprised us. We expected that caregivers in countries with strong familial care norms (i.e., where caregiving for aging parents is expected to be provided in their children’s home) would report worse well-being than those in countries with weaker familial care norms — because they were pressured into the caring role. We found, however, that only female caregivers’ well-being was worse in those countries. Female caregivers also have lower well-being in countries with fewer public transfers to support care for the aging. So, women in countries where there are strong social norms for familial in-home care – and where market or government subsidies for old age care are not readily available – may be more severely disadvantaged by caregiving responsibilities. This is consistent with research showing that female caregivers are more likely to be stressed, depressed, drop out of the labor force, and be sandwiched (caring for both a child and older adult).

That female caregivers in ostensibly coercive contexts report worse well-being may reflect role strain, related to lack of financial, socio-emotional, and other resources. Consider what it takes to provide care for an older adult, especially long-term. In the United States, taking time off from work to provide care for a family member is difficult, even a financial hardship for many. There is no federal paid family leave policy, and only about half of workers are eligible to take leave under the Family Medical Leave Act (meaning they may take up to 12 weeks off, mostly unpaid, without losing their job); thus, the economic implications of caregiving for a family member—be it a newborn, disabled person, or aging adult—can be disastrous for many families.

With over 65 million informal family caregivers in 31% of U.S. households, the current system is unsustainable. As the burden of care and the number of caregivers increase, so too will the social, economic, and health costs of caregiving. Middle-age adults who are beginning to experience their own health issues face compounding health effects of caregiving, leading to health risks earlier in life. This will inevitably strain the health care system as the number of caregivers grows.

What can we do to mitigate this bleak situation? First, we need a wide-ranging discussion about the vast challenges of informal caregiving in the current system, and how to promote equitable sharing of caregiving work in society. Second, we must address policy deficiencies, including the current piecemeal state-based approach that leaves many caregivers exposed. Potential starting points include broad policies to support caregivers through increased paid home care and community-care services. Recent innovative programs – like the one introduced for Pennsylvania, and federal respite care provisions – are first steps. Comprehensive federal policy changes that extend current family leave policies would also support caregivers, including paid and longer leave, and broader definitions of “family,” which would expand the range of people eligible and able to provide care.

Caregivers provide a valuable service to their loved ones and to society. Providing support for them is as pressing a social problem as providing care for the boomers heading toward old age. As older adults account for a larger share of the U.S. population, shifting demographics create unprecedented challenges for individuals and policy-makers alike. There is no better time to begin planning for this immediate future.

Comments 1

Counting the costs of caregiving: is there a better way forward? | Em News — January 5, 2015

[…] earlier version of this article was published on The Society […]