On December 16, 2012, a violent incident took place on the streets of New Delhi, India: a 23 year old student on her way back from the movies was gang-raped, disemboweled, and died from her injuries two weeks later. The incident sparked nationwide and global outrage; protests across the country; televised and social media discussion about women’s lack of safety in public spaces (and a very marginal discussion about women’s lack of safety in private spaces); the absences in the law on sexual violence and its enforcement; and what could be done to make Indian women secure.

#DelhiGangRape spanned both the online and offline with ease. Nirbhaya (‘the one without fear’), as the young student came to be known, lay in hospital holding on to life while the country raged and reacted. Candle-light vigils, night-time marches, solidarity sit-ins, were held for Nirbhaya across the country. In Delhi they were water-cannoned; more abuse happened during the protests. It felt like a sombre awakening, and we tweeted everything that we felt and experienced. That incident changed something, and we’re trying to piece together what did, and how and why.

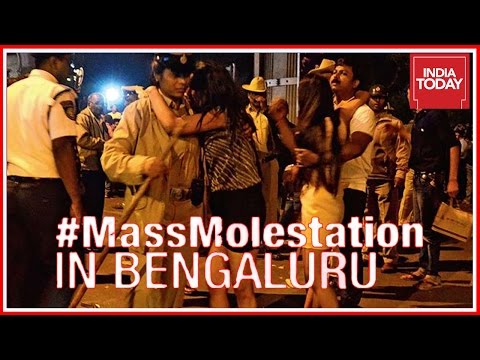

Incidents of public sexual assault of women in the southern-Indian city of Bangalore over New Year’s Eve have now come to light. One was the assault of a lone woman captured on CCTV, and the other was the story of a mass assault on many women in a central thoroughfare in the city among people bringing in the new year.

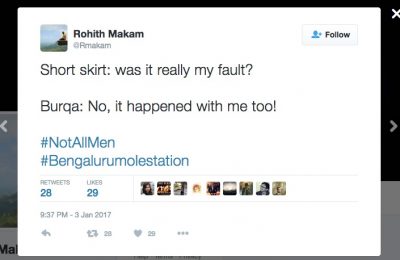

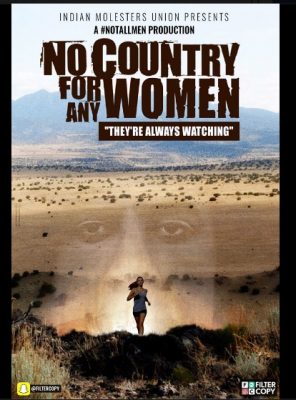

Protest marches are being organised around the country for January 21st. Bangalore had its “I Will Go Out!” march on January 12, an assertion of women’s rights to safety and confidence and fun in public spaces. Outrage has also been visible on Twitter and Facebook, but so have humour and levity. The hashtag #notallmen began to trend in India in response to a feminist group that surfaced #yesallwomen to show the extent of sexual violence Indian women face. Interestingly, #notallmen has received a resounding smack from across the Indian internet.

Early in 2017, a woman walked down a road alone in Bangalore and was accosted by two men on a motorbike. One jumped off the bike and started to grope her while she struggled to get away. Roughly seven kilometres away, hundreds of people were out on the central thoroughfare, MG Road, bringing in the new year. Images from that night document pandemonium, and there were reports of women being harassed and molested by many, many men. A similar sort of thing happened exactly a year before in Cologne, Germany. Police are now saying the mass assault incident never took place, although women have been reporting cases of assault that took place in bars, clubs and on the streets of the city that night.

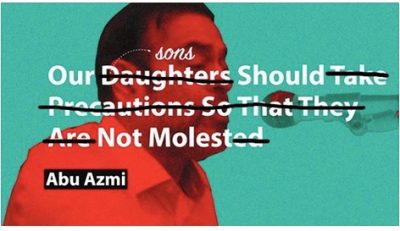

The attacks were met with familiar and tired gestures. Male politicians did what they always do when sexual assault occurs in public: blamed women for being out at night; blamed the influence of Western culture. (The evil influence of “Western culture” is a popular trope routinely deployed by self-appointed custodians of Indian culture to shut down any challenge to their nationalist notions.) “In these modern times, the more skin women show, the more they are considered fashionable. If my sister or daughter stays out beyond sunset celebrating December 31 with a man who isn’t their husband or brother, that’s not right. If there’s gasoline, there will be fire. If there’s spilt sugar, ants will gravitate towards it for sure,” said Abu Azmi, a politician inclined toward metaphor and sexism. A little correction later, Azmi’s words became the subject of Facebook likes.

After the New Year’s Eve attacks, the advocacy organisation, @FeminisminIndia , started collecting stories on Twitter with the #yesallwomen hashtag to demonstrate how common violence against women is in India. Very soon after, the #notallmen hashtag started to trend. What’s interesting about #notallmen is that it carries no particular cultural particularity – the defensiveness of men who cannot acknowledge structural sexism may have some cultural inflections, but the phenomenon itself appears to be fairly robust across local internets.

From the Huffington Post and Quartz India to the mainstream press, the criticism and trolling of #notallmen has been noticed. A deep thread started by the Buzzfeed India editor resulted in a collectively authored #notallmen parody based on Bohemian Rhapsody.

“Be careful” is one of those things Indian women hear all the time; we’re responsible for managing our family’s honour, so we have to be careful with it. Buzzfeed India released a video imagining what it would look like if Indian parents told their sons to ‘be careful’ lest they molest a woman.

Stand-up comedian Karthik Kumar takes on #allIndianmen poking fun at their what’s wrong with Indian men from them not knowing what the clitoris is, to not understanding what consent means. The video shows men in the bar looking a little sheepish and women laughing the loudest.

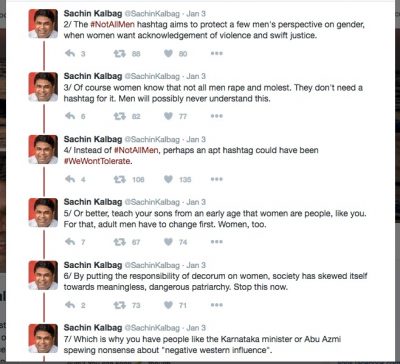

The senior journalist Sachin Kalbag had a rant about what is wrong with #notallmen.

Protest and activism online and offline can be oddly inspirational and emotional, and brittle and ephemeral at the same time. It’s unlikely that all the creators of memes are a new feminist online army online; sometimes it feels like we can talk about what’s wrong with Indian masculinity only by making it the subject of chiding humour. We’re not laughing at you. For now though, it’s trending to troll #notallmen and have a conversation that hasn’t been had enough.