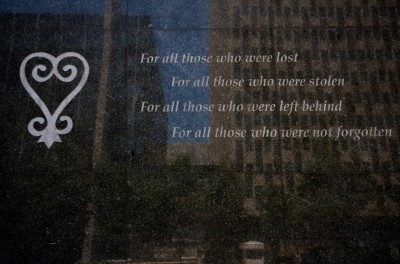

Towards the beginning of Italo Calvino’s novel Invisible Cities, Marco Polo sits with Kublai Khan and tries to describe the city of Zaira. To do this, Marco Polo could trace the city as it exists in that moment, noting its geometries and materials. But, such a description “would be the same as telling (Kublai) nothing.” Marco Polo explains, “The city does not consist of this, but of relationships between the measurements of its space and the events of its past: the height of a lamppost and the distance from the ground of a hanged usurper’s swaying feet.” This same city exists by a different name in Teju Cole’s novel, Open City. It’s protagonist, Julius, wanders through New York City, mapping his world in terms reminiscent of Marco Polo’s. One day, Julius happens upon the African Burial Ground National Monument. Here, in the heart of downtown Manhattan, Julius measures the distance between his place and the events of its past: “It was here, on the outskirts of the city at the time, north of Wall Street and so outside civilization as it was then defined, that blacks were allowed to bury their dead. Then the dead returned when, in 1991, construction of a building on Broadway and Duane brought human remains to the surface.” The lamppost and the hanged usurper, the federal buildings and the buried enslaved: these are the relationships, obscured and rarely recoverable though they are, on which our cities stand.

One morning early this spring, I stood at the intersection of Broadway and Duane and faced the African Burial Ground National Monument. It is, as Julius describes it, little more than a “patch of grass” with a “curious shape… set into the middle of it.” Inside the neighboring office building, though, is a visitor center with its own federal security guards, gift shop, history of the burial site and its rediscovery, and narrative of Africans in America. The tower in which it sits, named the Ted Weiss Federal Building, was completed in 1994, three years after the intact burials were discovered. (The “echo across centuries” Julius hears at the site of course fell on deaf developers’ ears.) In the lobby between the visitor center and the monument, employees of the Internal Revenue Service shuffle over the sacred ground as Barbara Chase-Riboud’s sculpture Africa Rising looks on, one face to the West, another to the East.

I visited the African Burial Ground National Monument during a spring break trip for a course called Exploring Ground Zeros. We spent much of our class time during the semester visiting sites of trauma near our university in St. Louis, trying to uncover the webs of historical and contemporary claims that determine their meaning. In East St. Louis, we tracked the (now invisible) paths of the 1917 race riot/massacre. In St. Louis, we walked through the urban forest of Pruitt-Igoe, stared aghast at the Confederate Memorial in Forest Park, and visited the Ferguson Quick Trip, the now (in)famous epicenter of the Mike Brown protests in which many of us continue to take part. In New York, we did the same, moving from the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory to 23 Wall Street to Ground Zero to the African Burial Ground National Monument. At each site, we analyzed architecture, commemorations, official literature, and wrote field notes, trying to measure the city by its relationships so that we might later recreate it in our assignments.

We also took pictures, and a few of us uploaded ours to Instagram. After visiting the African Burial Ground and the old Triangle Shirtwaist Factory (now an NYU building), I turned to Instagram, not only to preserve and catalogue my photographic evidence, but also to find more. Were these sites worthy of selfies and faux nostalgic filters? What hashtags blessed the posts? By exploring others’ photos, I hoped to learn more about how people engage with place, and how the sites in their photos exist in contemporary cultural memory. After all, though critics have focused on what Instagram and the selfie culture it enables say about our relationship to our social world and ourselves, Instagram reveals just as much about our relationships with place. In every selfie, there’s a background, a beautiful bathroom or sunset immortalized.

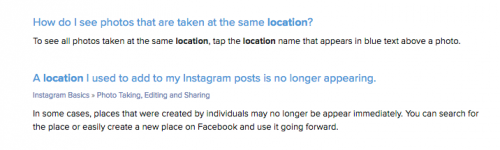

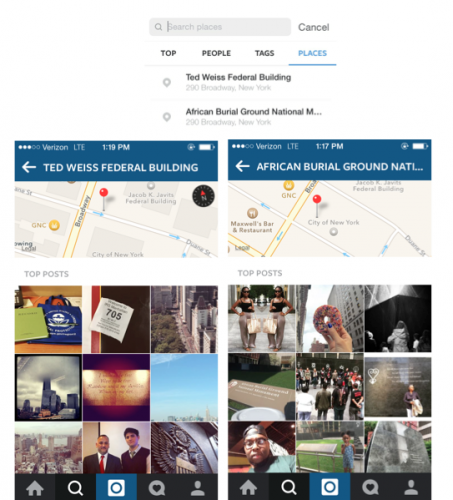

And so, I tagged my photos with the location at which they were taken, and looked through publicly posted photos under the same name. Quickly, though, I ran into a problem. As I mentioned, the African Burial Ground National Monument shares the same coordinates as the Ted Weiss Federal Building. Instagram, however, must recognize them as distinct locations. On its website, Instagram defines location as the “location name” added by the uploader. Simple enough. In the next paragraph, though, “place” replaces “location.” So, in the world of Instagram, “location” is “location name” is “place” is “place name”; it is also never plural. What’s more, these definitions form a curatorial practice. On Instagram, photos are organized by location name, and the newest update offers a “search places” option. This means the reality of social place- that of competing claims and layered meanings, physical or otherwise- cannot be found. Each place is neatly and securely tied to its single tag. This is no doubt an issue of convenience and loyalty to the wisdom “you can’t be in two places at once,” but the result is undeniable: on Instagram, the Ted Weiss Building has never heard of the Burial Ground.

What Instagram does offer is the possibility to “create a place,” a feature that most honestly reflects our everyday experience of place. Technically speaking, creating a place means attaching a manually entered location name to the coordinates where the photo was taken. Conceptually, though, this action has greater significance. Defining place, or place-making, anthropologist Keith Basso tells us, is “a common response to common curiosities… As roundly ubiquitous as it is seemingly unremarkable, place-making is a universal tool of the historical imagination.” Instagram does act as a tool for place-making, then, but its singular definitions prevent it from acting as a site from which to honestly make place. This is because it severely, unnecessarily limits the possibilities of the historical imagination. By equating “place” to “location name” and organizing photographs according to that name, Instagram creates a world in which places and locations are only as old as their names.

There are two more apparent obstacles in the way of Instagram’s historical imagination: oversaturation and amateurism. In the same essay, Keith Basso offers a compelling account of how historical imagination works to make place:

When accorded attention at all, places are perceived in terms of their outward aspects—as being, on their manifest surfaces, the familiar places they are—and unless something happens to dislodge these perceptions they are left, as it were, to their own enduring devices. But then something does happen. Perhaps one spots a freshly fallen tree, or a bit of flaking paint, or a house where none has stood before—any disturbance, large or small, that inscribes the passage of time—and a place presents itself as bearing on prior events. And at that precise moment, when ordinary perceptions begin to loosen their hold, a border has been crossed and the country starts to change. Awareness has shifted its footing, and the character of the place, now transfigured by thoughts of an earlier day, swiftly takes on a new and foreign look.

In photographic terms, this disturbance sounds exactly like Roland Barthes’ punctum, a term he coined in Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography to describe a significant and hidden detail in emotionally moving photographs. There he describes the punctum as “that accident (in the photograph) which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me).” Like Basso’s fallen tree, it “rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces.” It also shifts his awareness, transfiguring reality across time and space. Noticing the dirt road in a photograph by Kertesz, Barthes “recognize(s), with my whole body, the straggling villages I passed through on my long-ago travels in Hungary and Rumania.” But are punctums possible on Instagram?

Of course, our contemporary relationship with photographs on Instagram is quite different from Barthes’. In a post called “From Memory Scarcity to Memory Abundance,” Michael Sacasas asks, “What if Barthes had not a few, but hundreds or even thousands of images of his mother?” The answer, naturally, is a dramatic decrease in meaning. Sacasas writes, “Gigabytes and terabytes of digital memories will not make us care more about those memories, they will make us care less.” Surely, it seems unreasonable to expect Instagram users to view its photos with the same attention Barthes paid the photographs in Camera Lucida. And yet, all is not lost. Perhaps, Barthes’ punctum and Basso’s disturbance are merely displaced from an individual photograph to the application itself.

Imagine uploading a picture of your biology class at NYU and finding that hundreds have taken photos of the same room, but from the street, where garment workers jumped to their deaths when your lab room, formerly the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, was on fire. Even if you haven’t visited the site, looking at photographs from both perspectives might inspire the same prick the dirt road caused in Barthes. Describing that prick, Barthes writes parenthetically, “Here, the photograph really transcends itself: is this not the sole proof of its art? To annihilate itself as medium, to be no longer a sign but the thing itself?” An Instagram grid showing photos of the Ted Weiss Federal Building and the African Burial Ground National Monument simultaneously could, for some, be the thing itself. “The thing”, in this case, is not the texture of the ground or a traveller’s weariness, but the unexpected terror and sadness of a city showing its true foundations.

This combined grid’s disturbance is not only destructive, destabilizing conceptions of place, but creative. Indeed, according to Basso, “Building and sharing place-worlds… is not only a means of reviving the former times but also of revising them, a means of exploring not merely how things might have been but also how, just possibly, they might have been different from what others have supposed.” This function is particularly important today, as communities worldwide question the names they call their spaces. In the past few months, UNC Chapel Hill changed the name of Saunder’s Hall to Carolina Hall (Saunders was apparently a KKK leader); Aldermen in St. Louis are trying to change the name of Confederate Drive, which cuts through Forest Park, a 1300-acre public park; the student government at Rhodes University in South Africa voted in March to rename the university. How will Instagram incorporate contentious and changing place names? Today, there isn’t yet a geotag for Carolina Hall, but when there is, its photos will be kept separate from those taken at Saunder’s Hall. So, like the story of 290 Broadway, the UNC name change will be preserved and hidden. Students at UNC will create a new place, and before long it will have more photographs than the old. The archive of photos taken at Saunder’s Hall will continue to exist, static, and visible only to those who remember its previous name and implied owner.

Instagram makes room for these revisions, but not for places to present themselves “as bearing on prior events.” Allowing places to converse with their pasts—by allowing multiple geotags or associating geotags with time period(s) to display layers of names and meanings—would transform Instagram from a platform to share into a platform to converse and learn. Here, places would exist free of Instagram’s current architectural constraints, as palimpsests waiting to “inscribe the passage of time” and activate the historical imagination.

Jonathan Karp (@statusfro) is a recent graduate from Washington University in St. Louis, where he studied English literature and music.

Headline Pic via: Source