A few years ago (I don’t really remember when) someone on this blog (don’t remember who) [edit: it was nathan] lamented the fact that the increased visibility of our childhood indiscretions, thanks in no small part to Facebook, had never resulted in a change in how we forgive one-another for our past-selves. That instead of saying, “eh I was a kid once too” we continue to roll our eyes, clutch our pearls, and even deny each other jobs based on the contents of timelines, profiles, and posts. Today I’m starting to feel like such forgiveness might have to begin with ourselves because –as many of us might be experiencing at this moment—I have started a free trial of Apple Music and I am confronted with my old iTunes music purchases. I need to forgive myself for the purchase of A Bigger Bang when it came out in 2006. This is hard.

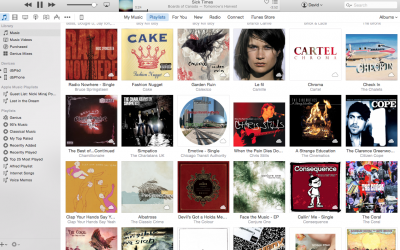

Apple doesn’t make it easy. There’s all this album art staring at you under the words “My Music.” It’s all there, in alphabetical order as if my decision to spend actual US currency on Madeleine Peyroux is the same kind of decision to let iTunes think I had “purchased” a Dead Prez CD and ripped its contents to the massive 80 gig hard drive that once inhabited my Macbook G4. Then there are all of these personal one-hit wonders that, for the life of me, I cannot remember from the album art (probably because it didn’t have any) but now stare at me like old friends who don’t look anything like they did in high school but their voice is unmistakable. Oh! You’re THAT track. Wow Magenta Lane’s Wild Gardens, I totally forgot about you.

Why do I have not one but two MC Hammer albums?

Remember that time Stephen Colbert had the Swedish-language hip-hop swing fusion band Movits! on his show and it was better than something like that has any business sounding? I’m not saying my decision to use half of the value of my fifth night of Hanukah iTunes gift card on that album was a good decision, but I suppose that’s just how we learn.

So now I’m wondering if the fact that I was one of those people that first heard Modest Mouse via Good News For People Who Love Bad News is the reason I fell so hard and completely into hating hipsters in the early 00s. I dunno, Building Nothing out of Something is an excellent album but, nine times out of ten, I’ll still choose to listen to Dashboard when I’m driving. I don’t know what that says about me.

Oof, Major Lazer is bad writing music.

Was anyone ever into Birdmonster in 2007? Pitchfork’s William Bowers in August of 2006 says that there were some “bloggers” that really liked them but he only gave No Midnight a 5.6. I remember them (sorta) as one of those British pop punk bands that had a moment in that time. The Fratellis, The Futureheads, Kubichek! All sound virtually interchangeable, now (and probably then).

If Spotify is the gabby friend that likes to tell all of your other friends that you listen to bad psytrance at the gym, iTunes is the parent that recommends The White Stripes “deep cuts” because remember all The White Stripes you listened to, don’t you like The White Stripes I thought you really liked them. The former is a performance, but the latter is a kind of meditation. Neither is more or less authentically “you” but both do sort of belie a misunderstanding on the part of designers and engineers, about what we do with our music and why.

The impulse to recommend is always already context collapsed. Recommendations come from paying attention to you and only you, regardless of context or co-present audience. No platform has yet mastered the when, how, or with whom of music listening and so we end up forced to explain Squarepusher to our aunt who we’re driving home from the airport as it comes up on your finely tuned driving Spotify radio station. That’s a good thing. Those moments should never be smoothed over by wearables that will report the audience to some onboard car computer designed to play the “perfect” Bruce Springsteen track off of Nebraska that everyone will tolerate.

We tend to think of them as sooth sayers, but algorithms meant to suggest “more that we love” are also products of what Carl DiSalvo calls adversarial design. Adversarial relationships are characterized by disagreement, but never in the Hegelian one-must-be-destroyed-to-realize-the-other sort of way. Adversarial relationships produce productive tensions that do useful political work through the juxtaposition and shifting relationships of individual actors. We come to understand how we relate to other people and the material world around us in moments where things don’t fit quite right. When that one Billy Joel track you like comes on when you’re with someone you are trying to impress, when a particularly raunchy song comes on during a dinner party. These are moments where we learn a lot and they might not be comfortable but that doesn’t make them unimportant.

Maybe then, the increased mutual understanding, the forgiveness that we were expecting to arrive with the ubiquity of the timeline, is still in the works. Maybe we will still get that, but it will take a lot more uncomfortable moments. In that time, unfortunately, social inequities will make the adversarial moments designed by and through algorithmically-induced context collapse more consequential for some and not for others. Gregarious algorithms can and have gotten people into serious trouble, I only have to worry about defending my purchase of that one Citizen Cope album from 2004.

Comments 4

Jim Malazita — July 1, 2015

It's funny, because the iTunes timeline/record reminds me of one of my favorite scenes from one of my favorite movies, High Fidelity, where John Cusack's character is auto-therapizing by rearranging his record album autobiographically.

The big difference, of course, is that the characters in the scene frame mediated trips down memory lane as comforting, even cathartic, whereas in the social media era these trips are framed as the sources of anxiety.

nathanjurgenson — July 1, 2015

was me: http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2012/11/26/glad-i-didnt-have-facebook-in-high-school/