Today seems like a good day to talk about political participation and how it can affect actual change.

Habermas’ public sphere has long been the model of ideal democracy, and the benchmark against which researchers evaluate past and current political participation. The public sphere refers to a space of open debate, through which all members of the community can express their opinions and access the opinions of others. It is in such a space that reasoned political discourse develops, and an informed citizenry prepares to enact their civic rights and duties (i.e., voting, petitioning, protesting, etc.). A successful public sphere relies upon a diversity of voices through which citizens not only express themselves, but also expose themselves to the full range of thought.

Internet researchers have long occupied themselves trying to understand how new technologies affect political processes. One key question is how the shift from broadcast media to peer-based media bring society closer to, or farther from, a public sphere. Increasing the diversity of voices indicates a closer approximation, while narrowing the range of voices indicates democratic demise.

By this metric, the research doesn’t look good for democracy. In general, people seek out opinion-confirming information. That is, we actively consume content that strengthens—rather than challenges—our views. For those of us who hide Facebook Friends, mute people/hashtags on Twitter, and read news from a select few sources, this may not come as a surprise.

This confirmation bias is algorithmically strengthened through what Eli Pariser calls a filter bubble. Many of the platforms and websites that feed us news and information are financially driven companies. These companies make money by selling space to advertisers, who pay according to the quantity and extent of users. That is, advertisers purchase eyeballs, so it behooves Internet companies to maximize eyeballs on their site, for as long as possible. This results in users receiving information that is already appealing to them. Pandora, for example, shows you music that’s similar to what you already listen to, while Google produces results that line up with the kinds of links you tend to click. In this way, our views and preferences are largely given back to us, creating a bubble that protects against, rather than invites, disagreement and debate.

Information in the digital age is plentiful, and the work of engaged citizens entails sorting through it to find what is relevant, meaningful, and useful. It seems that both individual practices of filtering and algorithmic filters work against a version of democracy in which political action stems from reasoned consideration of key issues from all possible sides. The Internet has not given us a public sphere.

But what if the public sphere is not the democratic ideal? What if, instead, the driving force of political participation is community and commiseration? This alternative democratic vision is the driving logic behind Brigade, a series of web and mobile tools that promise to help users become active political citizens.

CEO Matt Mahan explains that these tools allow people to “declare their beliefs and values, get organized with like-minded people, and take action together, directly influencing the policies and the representatives who have an impact on the issues they care about.” This is a model that embraces—rather than fights against—affirmation bias and algorithmic filter bubbles. And it does so in the service of political action.

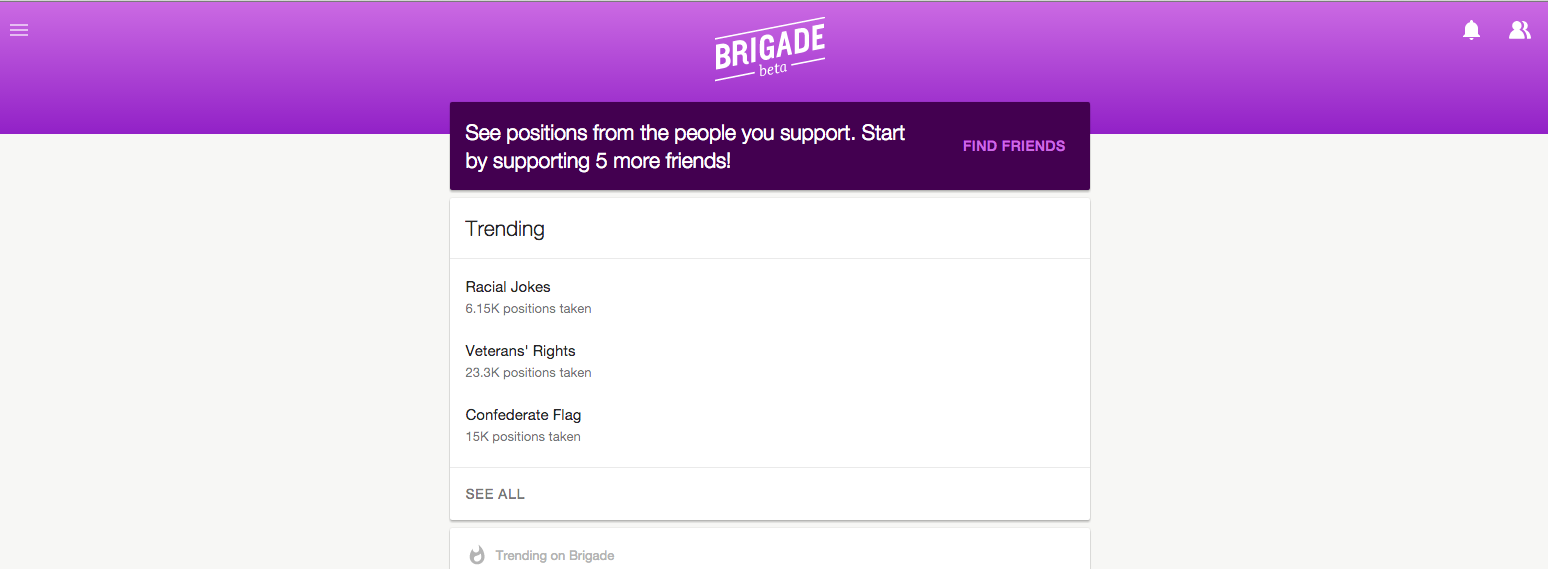

Currently in a beta version, Brigade is still invite-only. After requesting and receiving an invite, Brigade prompted me with a series of political questions, and encouraged me to answer more. After submitting my responses I could see how I compared with the general populace, and with those in my existing social media networks. I could also connect with others who share similar views, and learn about opportunities to get involved. It basically asks what I think, and then shows me my people. This is powerful. When a person states an opinion, as Brigade prompts users to do, it reflects a belief, but also, actively forms it. We are what we do, and stating that we believe something makes us believe it a little more firmly. Having established this belief, the user connects with others who agree, literature that supports, and events in which to participate.

In a strange way, Brigade itself embodies the will of the people. We filter, we affirm, we look for like-minded others. Brigade, as a political tool, helps us do it better. It is unclear if this will translate into votes and policies, but regardless, Brigade’s mere existence challenges us to reconsider the metrics of an ideal democracy. Perhaps, the public sphere will be dethroned.

Jenny Davis is on twitter @Jenny_L_Davis