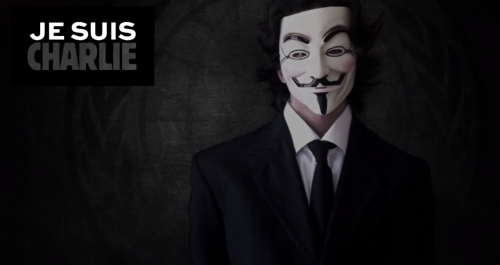

On January 9th, people donning the symbols of Anonymous promised a “massive reaction” to the shooting deaths of over a dozen people in Paris. Posted to YouTube and Pastebin under the hashtag #OpCharlieHebdo, Anonymous proclaimed, “It’s obvious that some people don’t want, in a free world, this sacrosanct right to express in any way one’s opinions. Anonymous has always fought for the freedom of speech, and will never let this right besmirched [sic] by obscurantism and mysticism.” Obviously what happened in Paris was a despicable act and I have little sympathy for the perpetrators but their actions weren’t random. What happened in Paris is the beginning of a fight between fanatics who hold polar opposite views on free speech and the battle lines being drawn are dangerously close to the ones that outline the War on Terror.

Fanaticism isn’t inherently a bad thing. Slavery abolitionists, according to the late Joel Olson, readily self-identified as extremists and fanatics. He defines fanaticism as,

the unconventional, extraordinary political mobilization of the refusal to compromise. Fanaticism is an approach to politics, driven by an ardent devotion to a cause, that seeks to draw clear lines between friends and enemies in order to mobilize friends and moderates in the service of that cause. It is willing to use direct action or other unconventional means to achieve this.

The world would probably be a better place if we had more people willing to claim fanatical beliefs over things like restorative justice, a universal basic income, or ending rape culture. Unfortunately, the far right has used fanaticism to a much greater effect, having achieving tangible goals like the closure of abortion clinics and austerity.

I don’t know what’s in individual Anon’s hearts but I think it is safe to say, without putting a large group of people into too small of a box, that people who are attracted to Anonymous are deeply committed to a radically strong interpretation of the right to free speech. It is probably the only thing that both favorable and critical accounts of the hacker collective agree on: that above all things Anons respect the ability of individuals to say whatever they want and hold nothing sacred.

There are however, lots of people who hold particular images and ideas to be very sacred. Most of those people probably saw that Charlie Hebdo published and chalked it up to the rest of the background racism and Islamaphobia that has become their everyday life. A small minority of that minority did not and thought those people should be severely punished. Nothing excuses mass murder but we should also recognize that so-called terrorists and the free speech fanaticism of Anonymous are the opposite poles of the same spectrum. Just because our secular sensibilities might make one end of the spectrum feel familiar, doesn’t mean one is more benevolent than the other.

I am not optimistic about the decision to use Anonymous tactics in this scenario. The people that are gearing up for #OpCharlieHebdo might not be affiliated in any way with past campaigns against Scientology or Steubenville rapists, so looking to the past for indications of what they will do in the future is, admittedly, a shaky proposition. On the other hand, there is enough commonality and overlap between operations that something approaching a modus operandi becomes visible. I don’t think anyone takes up the Guy Fawkes mask so they can have a reasonable conversation with someone they disagree with. Internal conversations within the group are probably made in good faith but an Anonymous operation is an adversarial process with a defined outsider.

Unlike previous battles that defined western governments as enemies to free speech, this operation seems to jibe nicely with powerful state actors. It certainly seems like an inviting environment for people that equate the Islamic faith with violence. It is a fanaticism that is willingly blind to the ways Charlie Hebdo has contributed to real, present, and deadly Islamophobia. By design Anonymous’ free speech fanaticism has to reject arguments like the one Sarah Wanenchak made on Sunday: “The problem with Je suis Charlie is that not everyone can be Charlie. “

Now you might say, “yeah but Jihadists murder people and Anons just bring down websites.” Certainly Jihad is more militant than Anonymous, but that distinction is fuzzy for as long as Anonymous’ attention and U.S. foreign policy are pointed in the same direction. Anonymous tactics have been used against western intelligence agencies with great effect in the past, so one is left to imagine what kind of hurt they could put on less powerful organizations. If hackers started fighting under the cover of, or to make way for, C.I.A drones, how much moral high ground can they take?

Regardless of how you answer that question one thing is unmistakably clear: radical free speech activists who don’t seem to understand or care about the ways structural oppression intersects with the right to publish or say whatever you want, think they have found their ideological opposite in so-called islamic extremists. Anonymous is an international movement but that doesn’t mean you automatically get a wide variety of opinions on the subject of free speech. In this particular battle, where the friends and enemies of Anonymous line up a little too neatly with western states’ foreign policy, there’s just too much potential for collateral damage.

David is on Twitter.

Comments 2

#OpCharlieHebdo is a Terrible Idea - Treat Them Better — January 13, 2015

[…] #OpCharlieHebdo is a Terrible Idea […]

Cybergovernance Reading List (2015-01-21) - Spatializations — January 21, 2015

[…] #OpCharlieHebdo is a Terrible Idea – Cyborgology […]