As a social scientist and theorist of technology, I follow some general rules in my thoughts and writings. One such rule is that I make no claims about the nature of people or the nature of things. Below, I do both. I then put these rule-breaking claims to use in beginning to make sense of the Washington school shooting, in which a reportedly “popular” and “normal” 15 year old boy shot 5 classmates before killing himself.

I begin with two claims about human nature:

First, humans need and develop with, culture—both material and symbolic. Second, humans’ internal emotional and psychological states are always in flux.

To the first point, Clifford Geertz makes the compelling case that humans are different from other animals not in our ability to create culture, but in our need for culture. Our instincts are comparatively quite poor, and so we must rely upon language, rituals, and objects (i.e., symbolic and material culture) to develop and survive.

To the second point, internal states, both emotional and psychological, are fluid rather than constant. These states change with both physiological and circumstantial shifts. For instance, hormone levels, brain chemistry, and blood sugar can drastically affect how one thinks and feels, as can external factors such as romantic love (both successful and not), money troubles, or even the weather. These shifts in internal mental and emotional states take place certainly over the life course, but also, even, from moment to moment. For a concrete if mundane example, think about yourself before and after your first cup of coffee. Or if you aren’t a coffee drinker, think of your mental state when lunch comes 30 minutes later than you had anticipated. It matters. A lot.

These two components of human nature—our need for culture and constantly fluctuating internal states— intersect at the location of individual action. Plausible lines of personal action are a joint product of culture—both material and symbolic—and an ephemeral feeling. Culture gives humans an array of social options and a corpus of tools (i.e., technologies). Action, or what someone does in a particular situation, depends on what is culturally available and what makes sense given a particular psychological and emotional state. For example, if I felt lonely, it would make sense to pick up the phone and call my mom, or even jump in the car for the two hour drive to my parents’ house. However, if letters were the predominate form of communication and horses the predominate form of transportation, or if parent-child bonds were not culturally normative, those lines of action would no longer make sense. Instead, it would perhaps make sense to visit a neighbor or ride into town. Alternatively, if I felt irritable (rather than lonely) my menu of cultural options would be entirely different.

Therefore, to understand human action requires an examination of these intersecting factors of internal state, cultural logic, and culturally available tools. If the action is problematic, we might think about which of these factors can best be changed to prevent such actions in the future.

Certainly, internal states can be altered with drugs and therapy, and symbolic culture can and has changed over time, but material culture—or technological objects—act as the physical tools with which actions are carried out. Remove the tools and the action becomes implausible, if not impossible.

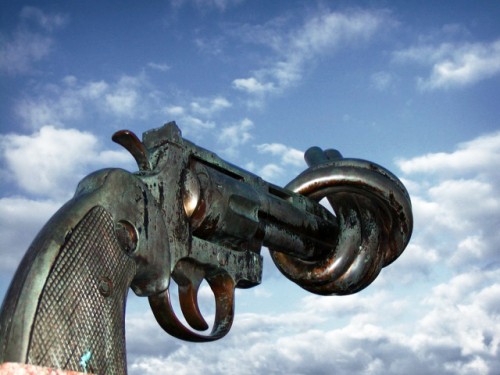

This equation, of course, is far from simple. Technological objects are created within the logics of symbolic culture, and hold multiple meanings and indeed, multiple uses. And yet, some objects class together in cohesive ways. When it is a troubling glue that holds such objects together, naming the class of objects is an important task. As such, I suggest technologies of violence as a shared heading for those pieces of material culture with the sole purpose of inflicting physical harm. Bombs, grenades, and of course, guns, fall into this category. These technologies and their usage may vary in the target of harm (e.g., human, animal, criminal, opposing army) and in the intention of the harm-inflictor (e.g., self-protection, protection of others, aggression, revenge). In the end, though, violence is the outcome of using these technological objects.

So let’s talk about guns, and about the role of this technology of violence in a deeply tragic event. Or stated differently, let’s look at how guns played into the equation of individual action as the piece of material culture which intersected with a 15 year old boy’s fluctuating mental state.

Jaylen Fryberg is not the “typical” school shooter. He wasn’t a loner. He didn’t wear a trench coat. He never wrote a manifesto. Rather, he played football, had lots of friends, and was elected to the Homecoming court just a week before. This atypicality (or perhaps, this ultra-typicality) have left media pundits digging to find his mental illness or tortured life circumstances. Watching the news over the weekend, I heard “experts” and newscasters question if the boy was bullied, if he endured racism, if there had been abuse at home. A lot of attention was given to some mopey (but not inherently alarming) Twitter posts about a recent breakup. People were reaching, it seems, to figure out the ways this boy, this killer, was broken.

But perhaps the answer is not that he was a broken person, but rather, that he was experiencing a break—a temporary moment of deeply troubling mental and emotional fluctuation. In this moment, he could have taken almost infinite lines of action. However, his access to a gun—to a technology of violence—shaped the action that he did, ultimately, take.

The idea that guns don’t kill people, people kill people, fails to grasp the intersection of human action and technological objects, just as the idea that guns are safe as long as they are kept away from the mentally ill fails to grasp the always present potential for a mentally healthy person to drop into mental illness. Internal states will, by nature, change, but the cultural object of violence will remain. This is a dangerous combination.

Certainly, as a society, it is important to address problems in symbolic culture such as bullying, abuse, racism, and an increasing normativity of lethal violence, just as it is important to address problems of mental health at the personal level. Understanding, however, that symbolic culture and internal states are always in flux, perhaps we should first address those technological objects with violence as their ultimate outcome. A first step in this endeavor is naming these technologies, creating a clear construction of what they do, and why they are used. We cannot know which lines of action will be personally plausible, but we can know that technologies of violence construct a logic and reality in which self and other harm are distinct possibilities.

Follow Jenny on Twitter @Jenny_L_Davis

Comments 2

James — October 30, 2014

This is a great post, Jenny.

Comradde PhysioProffe — November 1, 2014

Excellent post! My take home message is "It's a fuckeloade easier for someone with a gun to kill people than someone without a gun."