Go read “Dead And Going To Die”, a beautiful essay by Michael Sacasas posted today at The New Inquiry on the subjectivity expressed by people in old photographs. Part of why subjects look different in these images is they are expressing a different subjectivity to the camera lens. As the photographic gaze went from novelty to ubiquity, we’ve collectively oriented our selves to the camera differently. As Sacacas writes,

There is distinct subjectivity — or, perhaps, lack thereof — that emerges from most old photographs. There is something in the eyes that suggests a way of being in the world that is foreign and impenetrable to us

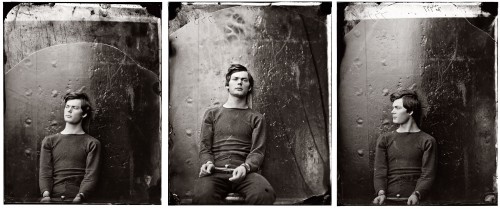

Specifically, he looks at the famous photographs of Lewis Powell that had previously interested Roland Barthes in his great study of photography. Powell was one of the co-conspirators of the Lincoln assassination and was tasked to kill the Secretary of State. Injuring many people, he failed and was captured. Before his execution, a series of photographs were taken that are famous for depicting a young man seemingly out of time, a snapshot of the past that looks disturbingly contemporary. Sacacas’ essay describes what is so hauntingly current about his image, and it goes beyond his hair style or clothes, but to how he has positioned himself in modern familiarity to the camera lens, which ultimately requires something a bit deeper: how one is concerned with oneself as a self.

To understand these photographs of Powell one must know their context. Powell attempted to resist photographic documentation by moving around (shutter speeds were slower then), and was threatened with a sword. In a moment of resignation, a profound and telling moment, Powell’s image was made as a fortune for the future. Bracketing the recent emergence of temporary photography, every photograph is a time capsule, a slice of the present frozen as past for the future. The content of this photographic time capsule hints at what subjectivity would become in the emerging era of visual documentation.

Specifically, Sacacas writes that what Powell learned to do is something subversive in his resignation to being photographed,

Powell could not avoid the gaze of the camera, but he could practice a studied indifference to it. In order to resist the gaze, he would carry on as if there were no gaze. To ward off the objectifying power of the camera, he had to play himself before the camera

What reads as modern indifference to the camera in an era otherwise noted for photographic performativity is instead a double-performance, the performance of indifference, the performance of the self as a self, of Lewis Powell as Lewis Powell.

While I agree with Sacacas that this is a profound moment, I think it’s profound in a very different way. While Sacacas maintains this is a new form of subjectivity, I would instead argue that it is a profound moment of revealing in explicit form what subjectivity has always been. I’m going to read into Sacacas’ essay what I think is presupposed but not explicitly stated, which is always a dangerous task, so I hope he can join in here and correct me where I’m bound to be wrong. Perhaps Sacacas’ account is more nuanced than the common understanding of the photographic self-performativity: at the invention of photography people learned to pose for the camera instead of just being themselves, and as documentation became more ubiquitous, posing and not-posing became confused and now we always act as if we’re on camera even when not.

I disagree with the fundamental assumption behind this story, however. Sacacas seems to assume there is some non-posed self that is “surrendered”, but what if we instead understand the self itself as a surrender, regardless of the adding or peeling away of reflexive and ironic layers of self-awareness? For instance, Michel Foucault argued, from the end of The Order of Things through his study of the History of Sexuality, that the self itself is not natural but instead a historical invention the product of modernity. If so, the process that Sacacas describes Powell undertaking isn’t a “watershed” moment of new subjectivity but instead what the self has always been.

But Sacacas and Barthes are right, the way Powell oriented himself to the camera was indeed novel. Instead of claiming this was a moment of an emerging new subjectivity but still retaining Sacacas’ general point, we might say that photographic, and now social media, self documentation mean an intensification of an existing trend, an intensification of our own relationship to ourselves, as I previously argued elsewhere in longer form.

The self, the intensity of identity as an omnipresent filter through which we experience, is not a given. It is something cultivated or not, to different degrees, in different ways, at different times, for different purposes. And identity is always a morality, not just a series of truths about who we are and what we do but also a declaration of what we won’t do; the ultimate expression of the self is always who we are not.

All of this leads me to wonder where our contemporary Lewis Powell’s are? Whose image today will be hauntingly familiar tomorrow? Or, perhaps instead a contemporary Powell would start somewhere different, perhaps where the self itself is understood as not natural or necessary. Perhaps it is subjectivity itself that is as doomed as the vacuous gaze of most early photographs. Perhaps in the future the very question of past subjectivies won’t even make sense.

Nathan is on Twitter [@nathanjurgenson] and Tumblr [nathanjurgenson.com].

Again, go read Dead And Going To Die, it’s wonderful.

Comments 7

Atomic Geography — October 23, 2013

Nathan, both you and Michael have written interesting and thought provoking essays!

But I think you both are making too little of the intricateness and danger of photography in this era. "(shutter speeds were slower then)" doesn't do it justice, so to speak.

An exposure of 15 seconds was common. This occurred only after the photographer conducted an complex series of tasks with explosive chemicals. http://www.npg.si.edu/exh/brady/animate/photitle.html

Both factors contributed to the look of portraiture at the time - a combination perhaps of not only boredom, but fascination with the process and fear of an explosion all proceeding being told "Don't move a muscle!"

Perhaps all this does reveal something about the prevailing subjectivity of the time. Perhaps impending death is what it took to try to ignore the photographic drama unfolding while sitting for one's portrait.

But in the personal writings of the era, diaries, letters and such, not to mention the literature of Whitman, Dickenson and Melville (reaching only for the proximate to time and place) there's plenty of modernity to go around.

“Bad Habits & Political Excitement”: Things to Read While Committed for Psychiatric Evaluation | Anthony Collebrusco — October 25, 2013

[…] Self Out of Time: […]

Michael Sacasas — October 25, 2013

Nathan,

Thanks for the thoughtful interaction with my piece. I think, as I read it, that we may not be too far apart. But I should also add that, having only an amateur's familiarity with sociology, I may not be using critical terminology with the precision and nuance it possesses within the disciplinary tradition.

That said, I would not tie my essay to any assumption of an essential self that existed before the camera. But I would say, given my rudimentary understanding of such things (and that's not false humility, by the way), that this period of modernity does seem to feature the emergence of a new way for the self to understand itself. It's a person's awareness or apprehension of the self that seems to evolve over time, and the mid-nineteenth century seems to be one of these critical moments in the evolution of the self-awareness. I would hesitate to claim that this kind of self-awareness was necessarily unknown prior to the nineteenth century.

I wouldn't put it this way, but say that we were to agree that person's have always been performing their identities; it doesn't follow that they were always aware that this was what they were doing. Coming to an awareness of it would elicit a new kind of subjectivity, by which I mean a new way of feeling what it was like to be a person in the world.

Atomic Geography's comment is helpful, too, in pointing to the literary manifestations of this emerging subjectivity. I adore Dickinson and I think that her poetry exemplifies this wrestling with a heightened self-consciousness:

Me from Myself — to banish –

Had I Art –

Impregnable my Fortress

Unto All Heart –

But since Myself — assault Me –

How have I peace

Except by subjugating

Consciousness?

And since We’re mutual Monarch

How this be

Except by Abdication –

Me — of Me?

I hope that I've understood your point and that this reply makes some sense in light of it. Thanks again for the thoughtful engagement!

Atomic Geography — November 2, 2013

Ran across this and thought of this post and discussion:

http://www.nextnature.net/2013/10/tristes-tropiques/#more-36862

The gazes into the modern camera (minus the drama of 19th century photographic process) of premodern humans are, well, human. The gazes of emerging into modernity humans into the pre-modern camera are posed and performed. The old camera just didn't afford human expression very easily.

The Presentation of Self to the Camera in Developing Countries | astuartblog — March 22, 2014

[…] [i] Sacasas, http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/dead-and-going-to-die/; Jurgenson, http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2013/10/21/self-out-of-time/ […]