Is there a point in speaking about original, fake or authentic when it comes to music these days? Before you roll your eyes and look for the exit button, you might want to read this post. It led me to realise that some debates which were hot when postmodernism came out of the oven are still relevant. A good take on this matter is Ted Cohen’s reflections on the notorious debate about art:

Although I have participated in discussions of what are is, I have always been in a negative position, arguing that someone’s attempt to say what art is fails, and until recently it did not seem to me that I had anything to say about what art is. And that was because, although I could think of reasons for denying what someone says art is, I could think of no way to begin thinking about what art seems (at least to me) to be. Now I have begun to find a way, and I am finding it by trying to understand why I (or anyone, for that matter) would ever seriously care to assert or deny that something is art. (Cohen, 1998: 154).

This blog post describes the art of music spammers who operate within the Echonest platform. Throughout the article you will have a tour, inviting you to walk the line that marks undesired and unwanted musical aesthetic and practice. According to the post, these musical spammers are using different methods for various reasons and are portrayed as hazards to the system. For example, they make a ‘fake’ piece of a hit song that hasn’t been officially released, they change names of various songs, they repeat the same few hundred songs in various combinations, or create “a clone of a song based around a single big riff which gets that big riff completely wrong”. These musical outlaws are then added to a ban list which will consequently mean that they will not receive recommendations from Echonest clients’ services, or in their apps. The main reasons they are banned is that they “could potentially slow or confuse our system; if it were music we needed to know about, that would mean it was time for some clever engineering to solve the problem — which we are perfectly willing to do when the situation calls for it — but for spam, why even bother? We leave most of them out”.

These allegations sound like all the previous accusations made towards spammers, for example Gy¨ongyi and Garcia-Molina argue that the definition of spam is ”any deliberate human action that is meant to trigger an unjustifiably favorable relevance or importance for some web page, considering the page’s true value” (Gy¨ongyi and Garcia-Molina, 2005: 2). Although the blog post indicates that “[t]his isn’t a matter of taste (so Coldplay and Raffi are in no danger). It’s because those banned artists are spammers”, it seems to me that it is very much about what constitutes ‘proper’ music and a ‘correct’ musical practice.

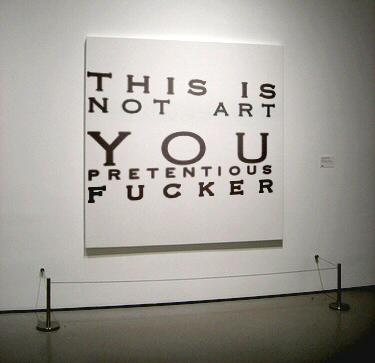

Back in the 1980s, when hip hop and electronic music started to bubble and take shape in accordance with postmodernism aesthetic sensibilities of the collage and remix, many musical purists claimed (some still do) that it’s not music at all but just a copy and paste of original music. Hey, even “Bill Cosby publicly criticised young people in the hip hop culture for their use of Ebonics instead of edited American English” (Price, 2005: 56). Hip Hop also brought to the forefront other forms of art such as graffiti which were initially banned (some still are), considered as a crime, and plainly bad style before they were sold as legitimate artefacts for $600,000. In both of the art forms we see similar strategies where art is stretching the boundaries of the appropriate place, shape and essence it should be delivered.

The segregation instigated by Echonest also puts me of the examples Sarah Thornton provides in her famous book Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital about how specific songs (The Beatles – A Day in the Life – 1967, Donna Summer – Love to Love You Baby – 1976, The Sex Pistols – God Save The Queen – 1977, Frankie Goes to Hollywood – Relax – 1984), which were prohibited from the BBC radio and received huge success because they were glorified as underground. The difference though is the fact that all these artists were identified, marked and framed as artists to begin with, and therefore the disappearance of their music was more noticeable and transformed into a promotional tool. But what happens when you are tagged as ‘non-artist’ or spam from the beginning?

Spam takes us to a rabbit hole trip to the binary realm of modernism where one must decide if a form of information, in this case a musical piece, is spam or not. This coalesces with the Internet design that shoves everything “in the language of discrete, continuous, and binary attributes (alive=1, dead=0)” (Fuller, and Goffey, 2012: 94). So who has the authority to determine what is ‘proper’ and ‘right’ music? Spammers are usually perceived as pranksters, tricksters and cheaters, but what if this practice could actually be considered as a form of art? In a way, both hip hop and electronic music have already crafted a form of art around reconfiguring/editing/remixing/shuffling by creating a different sort of musical amalgamation from pre-existing artefacts. So how do we distinguish between musical artefacts and what the blog posts terms as: not quality, not authentic and just plain awful? Would the creation of my friend Mise en Scene be considered as music or noise? Are we bound to be trapped in a black and white movie that doesn’t realises that there are 50 shades of grey (even if you think it’s awful), and maybe even some colour? As Finn Brunton argues in his book about spam:

[I]t is at once an exploit in the system, a specialized form of speech, and a way of acting online and being with others. It acts as a provocation to social definition and line drawing—to self-reflexivity and communal utterance. It forces the question: what, precisely, are we doing here that spam is not, such that we need to restrain and punish it? (Brunton, 2013: 14).

But there are other ways of spamming which deliberately misuses the communication channel. I have written before about the way artists buy their own music on Beatport in order to be ranked higher among the top selling artists, and also artists who tampered with the Top 100 Dj’s competition using their big families, Eastern geeks and bots. Those malicious interventions were made by those who are perceived as legitimate artists, who wanted to trick the system and receive more visibility which will consequently benefit their career. But the privileged position of the owners of various communication platforms also grants them the power to determine what they see as the true nature of a specific form of information. As Jean-Francois Lyotard argued “[t]he decision makers, however, attempt to manage these clouds of sociality according to input/output matrices, following a logic which implies that their elements are commensurable and that the whole is determinable… the legitimation of that power is based on its optimizing the system’s performance – efficiency” (Lyotard, 1994: 27).

Since music is a form of art, there might be a stronger tendency to be concerned from this process of tagging the right from the wrong. However, this incident, and the concept of spam in general, is an opportunity to question the way in which different institutions and platforms, around us categorize the information we are exposed to, the meta-narratives if you like, and invite us to challenge our approach towards junk/waste/noise. Reality is much more complex than rigid binary classification and coding as a form of language is a clear indication of the gaps of representation and the limits of computer language. As they say ‘one man’s waste is another man’s treasure’.

Elinor Carmi (@pinkeee_) is a PhD candidate at Goldsmiths College, writer, journalist, radio broadcaster and an electronic music addict. She blogs here.

Bibliography

Brunton, F. (2013). Spam: A Shadow History of the Internet (Infrastructures). MIT Press.

Cohen, T. 1998: “High and Low: Thinking about High and Low Art”, in: Korsmeyer, C. (ed.), Aesthetics, The Big Questions, Maldon, MA: Blackwell, pp. 171-177.

Fuller, M. & Goffey, A. (2012). Evil Media. MIT Press.

Gyongyi, Z., & Garcia-Molina, H. (2005). Web spam taxonomy. In First international workshop on adversarial information retrieval on the web (AIRWeb 2005).

Lyotard, J. F. (1994). The postmodern condition Jean-Francois Lyotard. The Postmodern Turn: New Perspectives on Social Theory.

Price Jr, R. J. (2005). Hegemony, Hope, and the Harlem Renaissance: Taking Hip Hop Culture Seriously. Convergence, 38(2), 55-64.

Thornton, S. (1996). Club cultures: Music, media, and subcultural capital. Wesleyan.

Comments 2

In Their Words (with special NSA section) » Cyborgology — June 9, 2013

[...] “who has the authority to determine what is ‘proper’ and ‘right’ music?” [...]

The Impact Of Technology Reading List: Using Social Media To Share Hate - — June 16, 2013

[...] “who has the authority to determine what is ‘proper’ and ‘right’ music?” [...]