Following Evgeny Morozov’s interesting article on Silicon Valley’s “pervasive and dangerous ideology” of fixing our reality with a simple click in order to perfect it (based on his upcoming book To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism), I could not help but wonder if this is a ‘new’ phenomenon after all?

Morozov’s notorious criticism towards the utopic discourse which hails from the ‘sunny side up’ area is accurate and sharp enough to expose how fake this silicon really is. He introduces the concept of solutionism which according to him is “an intellectual pathology that recognizes problems as problems based on just one criterion: whether they are ‘solvable’ with a nice and clean technological solution at our disposal”. The argument Morozov presents indicates that this is a relatively new phenomenon which has been made possible by technological innovations and applications, such as Google Glasses and even new start-ups that promise to make people Superhuman.

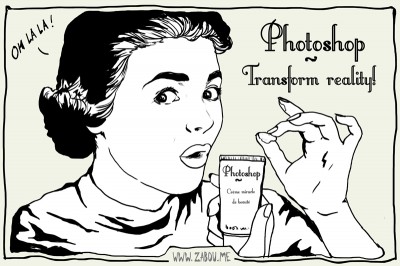

It seems to me that that the overemphasis on ‘new’ technological applications shifts and blurs the way in which various ideas have such prominence in our everyday lives, including surveillance, monitoring and Morozov’s solutionism. Women, for example, and especially women’s bodies, have been subjected to observation, regulation and perfection technologies for the past few centuries, in what Foucault would broadly call biopolitics (Foucault, 2007, 2008). This concept signified the transition from societies of discipline to societies of control, where the human body was the focus of technologies of power and knowledge which was portrayed in the concept of the normative ideal. The female body is subjected to these technologies, while performing ‘self-management’ which includes various strategies to adjust according to a norm, usually directed by a specific motif. However, the norm in this case is much more ideal than realistic; almost every female representation on media is modified to be thinner, taller, have perfect skin (preferably white) and no wrinkles through the constant refining/editing/patching of Photoshop (in order to become “Superhuman”). Photoshop (first appeared on the market in 1989) can be seen as the easy tool that allows solving the problem of what has been gradually understood to be a deviation from the norm, an anomaly.

The ‘normal’ female body in Western society is an imaginary and perfect – and mostly impossible to reach – fantasy. Luckily, there are many technologies besides Photoshop (because we need to solve the problems off screen as well) offered to women in order to solve their imperfection such as plastic surgery, whitening of the teeth or face, and even the simplest thing such as putting on makeup. In fact, it is almost impossible to find any woman who is not young, pretty, thin, white and without wrinkles in any media (mostly popular culture) representation (as was already eloquently elaborated by Naomi Wolf in The Beauty Myth How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women 1991). In that respect, how are “Silicon Valley’s technophilic gurus and futurists” any different from producers, copy-writers, label managers and literally anybody from the entertainment industry (Film, TV, Magazines, Music, to name a few)? Angela McRobbie has answered this quite accurately, that in fact “The media has become the key site for defining codes of sexual conduct. It casts judgement and establishes the rules of play” (McRobbie, 2004: 258). McRobbie discusses the movie Bridget Jones’s Diary as an example of yet another popular representation of this self-manageable female body:

Bridget portrays the whole spectrum of attributes associated with the self-monitoring subject; she confides in her friends, she keeps a diary, she endlessly reflects on her fluctuating weight, noting her calorie intake, she plans, plots and has projects…These popular texts normalise post-feminist gender anxieties so as to re-regulate young women by means of the language of personal choice (McRobbie, 2004: 261).

An interesting case study in this respect is the massive amount of criticism that the TV series Girls (HBO) has received, since it was one of the first times on screen that a female heroine, who was not skinny and pretty, received massive success. It was also one of the rare times on screen that real, intimate, humiliating and awkward experiences of sex were shown (much more grim than what the gitzy Sex and the City tried to exhibit). This was especially refreshing since according to Hollywood and the porn industry (which is synonymous with Silicon Valley and by that justifies its plastic name) we are all coming together and are extremely satisfied during and after having sex. How’s that for solving all sex problems and complexities of the female body?

Reality, as we experience it through the media, is already like a euphoric app, we only see an ideal, polished and moulded figure of a woman, and need to adjust ourselves accordingly. Luckily, like Google glasses, we are offered with many augmented realities which offer to solve our problems: Botox, hair rejuvenation in Melbourne, gym, diets, plastic surgery, push-up bras, varnishing, liposuction – which are meant to solve problems which were described as such, and then packaged as priced solutions. This eternal chase for a better figure has even inflicted actual pathologies which did not exist before such as bulimia and anorexia.

In addition, Women are also products offered to solve sexual problems or occasional problems of lack of entertainment; they can be bought as prostitutes (if you have a problem getting sex or not satisfied with what you have at home), strippers (if you have a problem of entertaining your buddies at your bachelor party), online entertainment and satisfaction (if you care for a morning glory) and a touristic venture (if you want to solve the problem of finding an interesting thing to do in your vacation e.g. – Pattaya). Therefore, women are not only offered many solutions to the problem, which is their imperfect body, they are also solving men’s problems, and that is hardly a new phenomenon.

Biopolitical technologies deployed on female bodies is a paragon example of how solutionism has, in fact, been part of our cultural practices and discourses throughout history, but there are other examples (see for instance Eva Illouz’s argument about psychology and the way in which from the 1920s it penetrated every social sphere and portrayed itself as the ultimate problem solver of the human soul, with a price, of course). Therefore, solutionism can be seen as a direct continuation of privileged people (usually white men) conquering social, biological, cognitive and physical spaces. It is also closely linked to neoliberal consumerism which offers to easily buy solutions for various problems, while artificially framing problems as such in order to capitalize on people’s desires, hopes and goals.

Imperfection is a price many women pay on a daily basis (physically, emotionally and economically); by modifying our bodies, by being modified in order to create an illusion in the media of a perfect idealized body, or selling our bodies as a product to solve someone else’s problem – women’s lives are being intruded upon from the moment we emerge into the world. Morozov mentions that “with Silicon Valley at the helm, our life will become one long California highway”, however, using the future tense, Morozov forgets that a large amount of Western population has already been driving this highway for quite a while, while wearing very different set of glasses.

Elinor Carmi (@pinkeee_) is a PhD candidate at Goldsmiths College, writer, journalist, radio broadcaster and an electronic music addict. She blogs here.

Refrences

Foucault, M. (2007). Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-78, trans. Graham Burchell, Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Foucault, M. (2008). The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978-79, trans. Graham Burchell, Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Illouz, E. (2008). Saving the modern soul: Therapy, emotions, and the culture of self-help. University of California Press.

McRobbie, A. (2004). Post‐feminism and popular culture. Feminist media studies, 4(3), 255-264.

Comments 3

quiet riot girl — March 25, 2013

hi

I would have been interested to see a mention of your rationale for only looking at 'female' bodies. It is clear that is your focus.

I write a lot about some of the issues you mention here, but more in relation to Men's Bodies. My blog www.quietgirlriot.wordpress.com

My rationale for focussing on men in this context is simple, and borne out by your piece - men are ignored as embodied people in culture in gender studies academia.

QRG

elinorcarmi — March 26, 2013

Hi QRG,

I appreciate your take on men's bodies, however, I personally think that they have actually received over and much more diversified exposure. By 'them' of course I mean white heterosexual men. As my text focuses on women but can definitely, just as well, focus on other bodies which receive different 'solutions' such as: lesbians, homosexuals, transgenders, Asians, Afro-Americans, people with different disabilities etc. These bodies, for me, receive much less attention, if at all, in various academic and popular discourses, than men do.

Elinor Pinke

Solutionism a new phenomenon? | Betteridge’s Law — June 4, 2013

[...] Solutionism a new phenomenon? [...]