Or: Lots of Words But Then An Awesome GIF, So Hang In There

Operating an automobile in an urban area is often quite frustrating. When you want to be driving, you’re often parked in traffic; when you want to be parked, you’re often driving around for a spot. Of course, there are apps for that: real-time traffic mapping apps from Google and others, and now we are also seeing so-called “smart parking” apps that display open parking spots by way of small sensors built in or near the parking space itself, fed into a network and then to a smartphone screen. A recent New York Times story on “smart parking” states that,

Smart-parking technology for on-street spaces is expensive, and still in its early stages […] Cities are marketing the programs as experiments in using demand-based pricing to reduce traffic congestion

The goal of “smart parking” is to give the city and individuals real time visualized data on which of those scarce city parking spots are occupied or not. Proponents hope this will mean easier parking and less traffic jamming. The idea of always knowing where those open parking spots are could be a huge relief. But, as the article above points out, these apps might not be so smart after all. The “smart” sensors will also make it much easier for law enforcement to ticket you when you’ve only been in your parking space moments too long. Also, new spaces are often taken as soon as they are available, and an app can’t help you much in that scenario.

To add to this, I’d like to briefly point out a different potential problem with “smart parking”: by focusing on making parking easier, we might also be encouraging more people to try to park. Like many tech-solutions-to-tech-problems, this answer could exacerbate the dilemma it is trying to solve when a better route may be to incentivize public transportation, biking, and other forms of transportation that don’t require looking for parking spaces in the first place. The logic that more parking information will lead to easier parking and less traffic congestion only holds, at best, if the number of cars looking for parking stays the same. The “smart parking” logic puts us in dangerous Robert Moses territory.

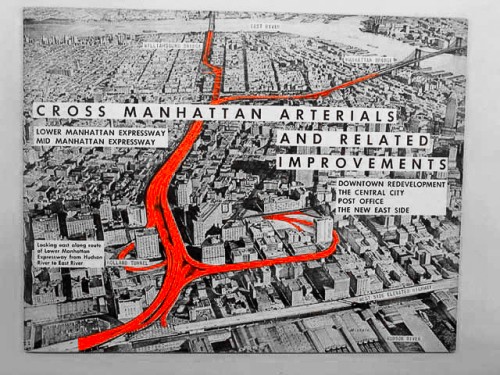

Robert Moses is famous for his concrete Haussmann-like accomplishments in and outside of New York City from the 1920’s all the way through the 1970’s. He built more and more highways and bridges in an effort to accelerate the vision of a future American car culture. His power to gather funds and build new projects was unprecedented and unchecked. Among many, many other projects, Moses built the Cross Bronx Expressway straight through existing neighborhoods. The displacement was abrupt and the devastation can still be seen today. According to his biographer, Moses was said to have purposely built tunnels with clearance too low for buses to pass through, discouraging public transportation as well as keeping those less wealthy off of his new roads.* Yes, he also built green parks, but built them far away for people to drive to (and he built those roads, too). After four decades of success, Moses planned a highway dead through lower Manhattan, which is where he met Jane Jacobs and her coalition of long-time neighborhood locals and recent gentrifiers as well as the changing cultural tide of the 1960’s. In what’s told as a modern-day David and Goliath story, Moses was repeatedly defeated and the highway pictured above was never built.**

I mention this mostly because I won’t pass up an opportunity to ramble on about NYC history (as anyone who has ever visited the city with me knows), but also because “smart parking” shares a logical error with Robert Moses’ vision. Indeed, what defeated Moses was the defeat of his underlying logic: that traffic congestion can be alleviated by adding more lanes of highway and more bridges. It seems intuitive enough: when sitting in a traffic jam you might wish for the addition of another lane. But this logic only holds if the number of cars stays the same. Instead, throughout Moses’ long power grip/trip, new roads didn’t reduce traffic; instead, the jams got worse, commutes got longer, more tolls were introduced, and drivers became more frustrated. In response, Moses built more, collected more tolls, and became more powerful. Traffic got worse. He built more. Et cetera.

What Moses failed to understand, what Jane Jacobs and others knew, and what New York City and the rest of the country took too long to realize is that adding more traffic lanes was increasing congestion. Open highways attract cars. Ease of driving meant more people were willing to drive more cars. New suburbs were built for commuting further and further away from the city. Driving became increasingly an option, and for the growing number of workers moving to the ‘burbs, a necessity.***

So-called “smart parking” certainly isn’t of a Robert Moses-like scope; those developing these apps are not (I hope) proposing to build massive concrete parking garages by demolishing existing communities. However, the logic—or more accurately, the logical error—is similar: providing an interface of all the unoccupied parking spaces will undoubtedly encourage more people to attempt to find parking.

Should I take the bus? subway? bike? Wait, I have the new smart parking app; let me check to see if there are open spots for my car. At least some people some of the time will choose the latter when they wouldn’t have before. The trouble of finding parking, like traffic congestion on urban streets, can be a prime reason why people in cities with cars leave their automobiles at home. Smart parking apps seek to remove that barrier, encouraging more new parkers.

That New York Times article above begins, “place ‘smart’ in front of a noun and you immediately have something that somehow sounds improved”, even when it has not. Since these parking apps could make spaces more scarce and encourage more cars on the road thereby increasing traffic, perhaps the “smarter” apps for making parking less of a hassle are those dealing with public transportation and biking.

__________________________________________________

*As Langdon Winner writes (citing this book, which I highly recommend),

Some two hundred or so low hanging overpasses on Long Island are there for a reason. They were deliberately designed and built that way by someone who wanted to achieve a particular social effect. Robert Moses […] built his overpasses according to specifications that would discourage the presence of buses on his parkways. According to evidence provided by Moses’ biographer, Robert A. Caro, the reasons reflect Moses social class bias and racial prejudice. Automobile-owning whites of “upper” and “comfortable middle” classes, as he called them, would be free to use the parkways for recreation and commuting. Poor people and blacks, who normally used public transit, were kept off the roads because the twelve-foot tall buses could not handle the overpasses. One consequence was to limit access of racial minorities and low-income groups to Jones Beach, Moses’ widely acclaimed public park. Moses made doubly sure of this result by vetoing a proposed extension of the Long Island Railroad to Jones Beach.

**Though, this left lower Manhattan to be transformed, as Sharon Zukin explains in Naked City, by wealthy gentrifiers instead of Moses’ brand of concrete rationalization.

***Facebook doesn’t cause loneliness, but there’s a good argument that this process did.

Nathan is on Twitter: @nathanjurgenson

Comments 35

Tim McCormick — January 2, 2013

> The logic that more parking information will lead to easier

> parking and less traffic congestion only holds, at best, if the

> number of cars looking for parking stays the same.

No, because better parking information can direct drivers where and when to go. Many studies have shown that a large part of all urban congestion is

caused by searching for parking, which could be largely removed by signaling. See for example Donald Shoup, "Cruising for Parking"

http://shoup.bol.ucla.edu/CruisingForParkingAccess.pdf.

Shoup's "The High Cost of Free Parking" is the standard work on dynamic pricing, and presents an exhaustive theoretical and empirical case for why this approach can improve the environment for not only drivers but other parties such as pedestrians, bicyclists, transit, and local residents/businesses.

In addition, recent research suggests that cancelling or delaying just 1% of vehicle trips can reduce traffic by 18%, if the right trips are targetted. See http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2012/cellphone-data-helps-pinpoint-source-of-traffic-tie-ups-1220.html.

So better information, to induce rational behavior change, can dramatically reduce congestion and make parking easier.

> providing an interface of all the unoccupied parking spaces will

> undoubtedly encourage more people to attempt to find parking.

This doesn't follow. Currently, with poor information, many people make trips in order to look for parking; with good information, many would not make the trip.

In any case, the goal in this case is to reduce congestion and make parking easier, not to reduce the number of people trying to find parking, or driving at all. If reducing number of trips or amount of parking is set as a goal, this can be managed more rationally by limiting supply or raising cost of the parking, rather than restricting information about availability.

David Banks — January 2, 2013

Great post Nathan! A couple of unrelated (to each other) thoughts-

1. Steve Woolgar and Geoff Cooper wrote an article back in the '99 (stupid paid JSTOR link: http://www.jstor.org/stable/285412) that claimed that the Long Island Expressway did, in fact, allow buses and that Jones Beach, (at the end of the LIE) even has a bus turn around and a few other accommodations. They go on to make the argument that this truth is, in fact, largely meaningless because we know Moses' projects were made to keep poor people away from nice stuff. Additionally, Winner's argument still works, but more as an Urban Legend, then a factual example.

2. When I worked in a planning department, my boss Peter Katz liked to say that increasing lanes to ease traffic is like buying bigger pants in an effort to lose weight. I've always liked that analogy, mainly because it shows just how wrongheaded this kind of thinking is. If you want to reduce something, you have to discourage it, not provide affordances for it or make it easier to do.

3. I think that "smart" parking is probably the best example of what Bloomberg himself calls, "building like Moses, with Jacobs in Mind." (This is quoted in both David Harvey's lastest book "Rebel Cities" and in the fantastic documentary "Urbanized") Here is a technology that doesn't require the bulldozing of thousands of homes (something that powerful people now realize should be done at a more appropriate time, like immediately after a massive storm) and seems to help New Yorkers live easier lives in places they already inhabit. In some ways, our smartphones have taken the place of what Jacobs called the "Public Character." This is the person that might hold your package deliveries while you're on vacation or hold a key for out-of-town friends coming to visit while you're at work. They solve logistic and information problems by simply always being around. Usually they're local store owners or retired folk with gregarious personalities. When people say that facebook makes us lonely, my stock answer is that the suburbs made us lonely, and Facebook is just capitalizing on that pre-existing loneliness. It does some things really well, and it does other things very poorly. When we physically live so far from each other, the public character cannot exist. They cannot physically see and hear enough human activity to fill that role. "smart" things seem to fill some of those roles. I can tell when my package has been delivered or I can reserve a cab, or leave a visiting friend a message about when you'll be coming home from work. Its important that we look at what aspects and qualities of "public characters" we want to recreate or (to use Latour's vocabulary) delegate to nonhuman actants.

David Banks — January 2, 2013

Also, if I may play Amazon autosuggest bot for a moment:

Readers who read "Smart Parking and the Robert Moses Mistake" might also enjoy:

"I have seen the Future! Ethics, Progress, and the Grand Challenges for Engineering." by Herkert and Banks (2012): http://library.queensu.ca/ojs/index.php/IJESJP/article/view/4306

Rob — January 2, 2013

Good post -

pedantic quibble: think you have NYC expressways misidentified. BQE = Brooklyn Queens Expressway

notable Moses debacle viz. expressway building (one discussed I think by Marshall Berman in All That is Solid Melts Into Air) is the Cross Bronx Expressway

Roger Critchlow — January 2, 2013

This immediately raised a vision of parking scalpers descending to occupy the most desirable parking spaces and reselling them on Craigs list.

Today's Scuttlebot: A Trip to North Korea and 10th Grade Technology - NYTimes.com — January 2, 2013

[...] next in technology? A glimpse into the future through the eyes of a teenager. – Brian X. Chen‘Smart Parking’ and the Robert Moses Mistake Thesocietypages.org | One lesson from Robert Moses: smart parking could make traffic worse (and a [...]

Smart Parking, and Public vs. Professional Academia | tjm.org — January 2, 2013

[...] student Nathan Jurgenson wrote a post in reply “‘Smart Parking’ and the Robert Moses Mistake,” on a blog he co-edits, Cybergology, which is hosted as part of The Society Pages, a social [...]

nathanjurgenson — January 3, 2013

tim, the point you are making that i find most interesting is,

"Currently, with poor information, many people make trips in order to look for parking; with good information, many would not make the trip."

i really wish i had put this point in my article, so super happy you brought it up!

i don't think this will be the case. the smart parking apps will not consistently display that there is no parking, else no one would use them. in order for the apps to be useful they need to give at least the illusion of potential parking. they exist to encourage people to find parking, especially as some of them are funded by money placed by parkers into parking meters. i think the apps existence, and potentially monetary incentive, pushes for more people to park.

Friday Roundup: January 4, 2013 » The Editors' Desk — January 4, 2013

[...] Get on it! This week, Nathan Jurgenson also started a conversation on public soc with his “‘Smart Parking’ and the Robert Moses Mistake,” Jenny Davis reconnected with waste, and David Banks reviewed Coding [...]

Nathan (not jurgenson) — January 4, 2013

Correct me if i did not do a close enough reading, but what empirical evidence do you have to support the claim that smart parking encourages more new parkers? And why do you believe that one traffic phenomena is generalizable to another? I fail to be swayed by your assertion that city and street planning can be boiled down to one single "logic."

Weekend Reading « Backslash Scott Thoughts — January 6, 2013

[...] Smart Parking and the Robert Moses Mistake. [...]

Jim H — January 6, 2013

I don't think that smart parking will make any difference the way you think. There is a physical limit to the numbers of cars that parts of a city can pack in. Continually making wider and wider freeways increases capacity which will be filled up by the 20th century automobiles. How's about this: once you get this very efficiently packed volume of parked cars to the maximum physically possible, there would have to be a single signal to all other cars: LOT FULL. Thus nobody slows down there, speeding up traffic though that neighborhood until some people leave.

Until then, the car tells you where the next supply of parking places is. Click on parking space X from two blocks away, and the place is marked as used to all other cars looking to park. Only one driver slows down, with signal automatically started. No horns, no wasted obscenities.

Jim H — January 6, 2013

Of course, the risk would be that the parking could get so lucrative that the city would tear down all the surrounding places to visit so you could park there.

Parking Wars, Public Soc, and Professional Thinkers » The Editors' Desk — January 7, 2013

[...] In his original post, Jurgenson suggests that, in stark contrast to its laudable intentions, smarter parking could actually create more parking problems by encouraging people to drive around even more, since the annoyance of parking won’t be quite the disincentive it is currently. Jurgenson bases his critique on what he calls the “Robert Moses Mistake”—the unintended consequences of creating more and better freeways. McCormick, in turn, argues that Jurgenson doesn’t really know much about the impetus and ideas behind smart parking, its realities as a social policy innovation, or the actual research on parking and driving among urban planners and policy makers. [...]

What is High Tech? » Cyborgology — January 8, 2013

[...] tech is usually not civil engineering (unless we are talking about the highway operations center or “smart” parking), language (even though it is a technology), or carpentry. High tech is a nebulous, contestable [...]

Erik Griswold — January 10, 2013

I prefer the analogy of "Peeing your pants to keep warm" given the expediture of resource(that potentially could be used for something else), the environmental impact, and the amount of time these asphalt expanions offer any "relief".

tech. magazine: issue 8 – all the stories in one place - FourTech Plus — January 17, 2013

[...] James Fallows, The Atlantic Jenna Wortham, New York Times Chris Mills, Gizmodo UKNathan Jurgenson, The Society PagesInform Rip Empson, TechCrunch Steven J Vaughan-Nichols, ZDNet Nancy Gohring , Citeworld Stacey Cole [...]

tech. magazine: issue 8 – all the stories in one place | allcom.se — January 17, 2013

[...] Nathan Jurgenson, The Society Pages [...]

tech. magazine: issue 8 – all the stories in one place - Plugged Into The Matrix — January 17, 2013

[...] Nathan Jurgenson, The Society Pages [...]

tech. magazine: issue 8 – all the stories in one place - Need2review | Need2review — January 17, 2013

[...] Nathan Jurgenson, The Society Pages [...]

“Smart Parking” and the Robert Moses Mistake | Civic Strategies | Scoop.it — January 25, 2013

[...] Most people consider "smart parking" (which is a way of pricing parking according to demand) to be a step forward by cities that are looking to tame their crowded streets. But could it have unintended consequences? A writer questions what the effects might be of making it easier to find a parking space in an urban environment . . . and, in the comments that follow, some defend the idea. [...]

Links da Semana | Grupo de Pesquisa em Cibercidades :: GPC :: PPGCCC/Facom/UFBA — February 27, 2013

[...] Artigo – Estacionamentos inteligentes podem aumentar a procura por vagas? - “Smart Parking” and the Robert Moses Mistake [...]

Google Maps Can’t Kill Public Space (A Belated Reply to Evgeny Morozov) » Cyborgology — June 5, 2013

[...] makes about as much sense as buying bigger pants to lose weight—it just doesn’t make sense. Efforts to reduce car traffic through better information will probably yield similar results. Making it easier to drive will never reduce the amount of [...]

In Praise of Messy Cities | supernicecity — August 19, 2013

[...] smart city rhetoric echoes 60s and 70s »> highrises & highways Pruitt Igoe & Robert Moses and their unintended socio-environmental consequences; also [...]

Cities of Sand: Silicon Valley Corporate Subdivisions » Cyborgology — October 8, 2013

[...] separated so that they may reach the sorts of optimal efficiencies that Le Corbusier promised and Moses tried to deliver. But unlike Moses or Le Corbusier, the planners and corporate patrons of Silicon Valley are making [...]

#Review Actor-Network Theory’s Approach to Agency » Cyborgology — January 31, 2014

[…] or what they built still plagues us regardless of significant changes in collective will or desire (Robert Moses is still messing up your […]