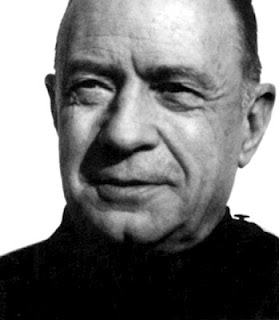

Last month the Heartland Institute, a climate-denying “think tank,” plastered Ted “The Unabomber” Kaczynski’s scowling face on a series of billboards in Chicago.

I still believe in global warming,” the copy read. “Do you?

Kaczynski has long been the figurative poster boy for technophobic insanity, of course, but the Heartland Institute made it literal. The billboard campaign was quickly recognized as a miscalculation and withdrawn, but it served as a reminder of what a gift Kaczynski turned out to be for some of the very enemies he sought to destroy. It also served as a reminder of how egregiously he misused the ideas of a philosopher who is revered as a genius by many people, myself included.

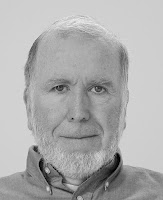

I refer to Jacques Ellul, author of The Technological Society. Ellul died 18 years ago last month; this year marks the hundredth anniversary of his birth.

David Kaczynski, Ted’s brother, has said that Ted considered The Technological Society (published in French in 1954 and in English ten years later) his “bible.” That’s easy to believe when you compare how closely the Unabomber Manifesto follows – once you weed out its many hate-filled digressions – Ellul’s ideas.

Kaczynski claimed in all humility that half of what he read in The Technological Society he knew already; he discovered in Ellul a soul mate rather than a teacher. “When I read the book for the first time, I was delighted,” he told a psychiatrist who interviewed him in jail, “because I thought, ‘Here is someone who is saying what I’ve already been thinking.'”

So, what are Ellul’s ideas on technology? His most central point was that technology has to be seen systemically, as a unified entity, rather than as a disconnected series of individual machines. He also argued that technology is as much a state of mind as a material phenomenon, in part because human beings have been absorbed into the technological complex he called “technique.”

Ellul defined technique as “the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of human activity.” While technique isn’t limited to machines, machines are “deeply symptomatic” of technique. They represent “the ideal toward which technique strives.”

These quotes hint at Ellul’s conviction that technique has become almost a living entity, a form of being that drives inexorably to overtake everything that isn’t technique, humans included. The belief that humans can no longer control the technologies they’ve unleashed – that technique has become autonomous – is also central to his thought. “Wherever a technical factor exists,” he said, “it results, almost inevitably, in mechanization: technique transforms everything it touches into a machine.”

Along the way technique’s drive toward completion does provide certain comforts, Ellul acknowledged, but overall its devastation of what really matters – the human spirit – is complete. “Technique demands for its development malleable human ensembles,” he said. “…The machine tends not only to create a new human environment, but also to modify man’s very essence. The milieu in which he lives is no longer his. He must adapt himself, as though the world were new, to a universe for which he was not created.”

Ellul’s reputation among scholars is mixed. He has his admirers, but many philosophers of technology consider him a nut. The principle objection is that he reifies technology, imputing to it a life and will of its own. It’s true that Ellul’s language often gives that impression, but again, his definition of technique includes human beings. Without their assent and participation its vitality would collapse.

Ellul’s unrestrained literary style also won him no friends in the academy. He had no interest in scholarly convention. His books include few citations of other works and even fewer qualifications – Ellul never doubted his own argument. His writing is filled with colorful description, irony and righteous anger. He’s more direct than the stereotypical French intellectual, and thus more fun to read. Nonetheless, his erudition is extraordinary, his insight incomparable.

He did occasionally go over the top. Perhaps the most embarrassing moment in The Technological Society comes when, in the process of making the quite reasonable point that technique finds a way to co-opt any political movement or art form that resists it, he dismisses jazz as “slave music.”

A third reason Ellul is considered something of an oddball in academic circles is his faith. Throughout his prolific career he divided his time between books on technology and books on religion. (That he could follow Jesus and still appreciate Marx will perhaps be more surprising in America than it would be in France.) He was a theologian of subtlety and depth, but one suspects that for many his religious beliefs undermine rather than enhance his credibility.

Ted Kaczynski managed to ignore Ellul’s religious views altogether. Where Kaczynski sought with his manifesto to overthrow technology by force, Ellul in The Technological Society explicitly declines to offer any solution at all. Ellul insisted his intention was only to diagnose the problem, not prescribe a treatment. He also insisted, however, that as despairing as his analyses often seemed, he was no pessimist. There’s always room for hope, Ellul said, even if it has to rely on the possibility of miracle.

Another person who’s found Ellul’s thought amenable, though he doesn’t seem to realize it, is the technophilic writer Kevin Kelly. In his recent book, What Technology Wants, Kelly devotes several pages to the Unabomber Manifesto, calling it, with apologies, one of the most astute analyses of technology he’s ever read. This is largely because Kelly agrees with Kaczynski that technology is a dynamic, holistic system – the “technium,” he calls it – that behaves autonomously. “It is not mere hardware,” Kelly writes; “rather it is more akin to an organism. It is not inert, nor passive; rather the technium seeks and grabs resources for its own expansion. It is not merely the sum of human action, but in fact it transcends human actions and desires.”

That’s as Ellulian as it gets.

The major difference between Kelly’s view of technological autonomy and Ellul’s is that Kelly sees the technium/technique as a force that ultimately increases human freedom while Ellul believed the opposite.

For Kelly, humans + technology = an evolutionary extension of the species.

For Ellul, humans + technology = mutation.

Kelly makes no mention in his book of Ellul, although he frequently cites Langdon Winner, a professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute who happens to be one of Ellul’s staunchest defenders. Winner’s 1977 book, Autonomous Technology, which Kelly credits as a key influence on his thinking, is a seminal contribution in its own right, but it also wears its debt to Ellul on its sleeve.

On one of the dozens of pages that mention Ellul, Winner offers what I suspect is an intentionally measured assessment of The Technological Society, calling it “less an attempt at a systematic theory than a wholesale catalog of assertions and illustrations buzzing around a particular point.” Still, he adds, “It is possible to learn from the man’s remarkable vision without adopting the idiosyncrasies of his work.”

[Langdon Winner is one of the scholars scheduled to speak at a centenary celebration of Ellul’s life and work at Wheaton College in July.]

This post is also available on Doug Hill’s personal blog: The Question Concerning Technology.

Comments 13

david ronfeldt — June 8, 2012

Good post; good points. I’d also commend Ellul’s dark later book The Technological Bluff (1990), and have a few quotes at hand to offer from it. Accordingly, the entire, optimistic, uncritical “discourse” about the new technology, and the pervasive insistence that people must become acclimated to it, represent a form of “terrorism which completes the fascination of people in the West and which places them in a situation of ... irreversible dependence and therefore subjugation.” Thus a new “aristocracy” is leading people to believe that a computerized society is inevitable, and that they have no choice but to succumb to it. “The ineluctable outcome is dictatorship and terrorism. I am not saying that the governments that choose this as the flow of history will reproduce Soviet terrorism. Not at all! But they will certainly engage in an ideological terrorism.” The irony for Ellul is that people are being led to think the technology will enhance their freedom, when in his view it is bound to limit their freedom.

Doug Hill — June 8, 2012

Thanks, David. I agree, The Technological Bluff is a powerful book and a worthy successor to The Technological Society. The quotes you provide give a good sense of Ellul's uncompromising point of view.

dewar — June 20, 2012

Does Ellul address Marx? Capitalism?

Also, thanks for the lucid prose. I always appreciate a writer who can take others' ideas and make them comprehensible (and enjoyable) to dimwitted me.

Doug Hill — June 20, 2012

Thanks Dewar. Yes, Ellul was conversant with and sympathetic to Marx (I touched on this in passing in the essay). As for capitalism, Ellul in The Technological Society underplayed the emergence of corporate capitalism as the predominant controlling force, focusing most of his attention on "the state." On the other hand he devoted a substantial amount of attention to technique's transformation of human beings into "economic man" -- in other words, as creatures whose sole worth is calculated in terms of profit and loss.

Dale — July 8, 2012

Certainly the subject is vastly interesting. The Boston Globe article was far too short; it barely gave the gist of Ellul's arguments, nowhere near enough to judge them. But I can't blame you for that, the Globe didn't give you nearly enough space.

I can't avoid remembering the article "Harvard and the Making of the Unabomber" by Alston Chase out of the Atlantic, from which I have saved this in my commonplace book:

"But the truly disturbing aspect of Kaczynski and his ideas is not that they are so foreign but that they are so familiar. The manifesto is the work of neither a genius nor a maniac. Except for its call to violence, the ideas it expresses are perfectly ordinary and unoriginal, shared by many Americans. Its pessimism over the direction of civilization and its rejection of the modern world are shared especially with the country's most highly educated. The manifesto is, in other words, an academic -- and popular -- cliche."

In any case, I was wondering if Ellul's opposition to technology extended to the most radical and disruptive technology that we've got good information on -- the introduction of agriculture (about 10,000 years ago, after 90,000 years or more of foraging life). That certainly altered almost everything about human life (many of them not for the better) and allowed the rise of the State and eventually the Business.

At any rate, the Ellul symposium at Wheaton College can strike back at technology: Everyone present should forswear use of the airplane, the automobile, the railroad, the printing press, and modern medicine. If not, they're saying that "we have to say that there are limits, but we do not exclude anything we find personally useful or desirable".

As for the market, the soundest analysis I've seen was written by two Hungarians, in the era of Communism:

"Thus the validity of the free market came to be questioned first in the market for intellectual products, for the creative intelligentsia found it unworthy that an impersonal market should determine the value of their works. Soon afterward appeared those ideologies which called into question the validity of the market in general, seeing in it the fundamental evil and in commodity relations and money the antithesis of culture; and so they advanced a program of humanization with the elimination of competition and of market relations in general at its core."

-- "The Intellectuals on the Road to Class Power; a Sociological Study of the Role of the Intelligentsia in Socialism" by George Konrad and Ivan Szelenyi, 1979

The Tech-Savvy Amish « The Frailest Thing — August 4, 2012

[...] the Unabomber, however, most critics of technology are not interested in abolishing “technology”; nor are [...]

Revisiting the Clock Tower: Scaling Technology » Cyborgology — September 13, 2012

[...] pre-supposed the machine, although the machine was also its ultimate expression. Doug Hill, on this blog, has done an excellent job of identifying some of the most important parts of Ellul: The belief [...]

Always Already Augmented » Cyborgology — March 1, 2013

[...] what food stamp recipients can buy, I care. But I am critical of the sociotechnical apparatus and underlying ideology, not just the computer networks. When I see my students citing Wikipedia or constructing sloppy [...]

Has Morality Become a Skeuomorph? » Cyborgology — March 9, 2013

[...] I’ve explained elsewhere, Ellul pictured technology as a unified entity that relentlessly and aggressively expands its range [...]

Google Maps Can’t Kill Public Space (A Belated Reply to Evgeny Morozov) » Cyborgology — June 5, 2013

[...] unconnected units (cars and packets), and connects people quickly with a ruthless kind of self-justifying technique. Whatever is in Google’s interest is probably big and complex, but not necessarily California [...]

David — May 19, 2014

Could you possibly tell us where you read about Kaczynski's fascination with Ellul? I would like to cite that source. Your help would be greatly appreciated.

Doug Hill — May 19, 2014

David -- Several books on Kaczynski mention his fascination with Ellul. One is Alston Chase's "Harvard and the Unabomber." See, for example, page 92 (hardcover edition), where Chase writes that Kaczynski told the psychiatrist who evaluated him after his arrest that Ellul's The Technological Society had been very important to him, adding that when he first read the book he thought to himself, "Here is someone who is saying what I had already been thinking." There are several other references to Ellul's influence on Kaczynski in Chase's excellent book (which is a much more comprehensive examination of Kaczynksi's life and terror campaign than the title suggests).