Start at 13:42 – 15:37 for images of Zuccotti Park being dismantled

The clearing of the Occupy Wall Street demonstrators from the streets of various cities over the past few weeks has been a strikingly naked demonstration of the characteristic properties of what Jacques Ellul called “technique.”

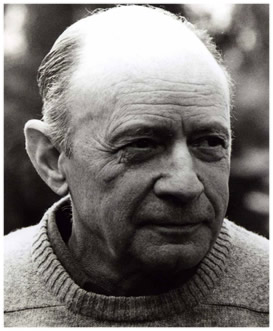

Like other philosophers, Ellul thought of technology more as a state of being than as a collection of artifacts. “Technique” is the word he used to describe a phenomenon that includes, in addition to machines, the systems in which machines exist, the people who are enmeshed in those systems, and the modes of thought that promote the effective functioning of those systems.

In The Technological Society, Ellul called technique “the translation into action of man’s concern to master things by means of reason, to account for what is subconscious, make quantitative what is qualitative, make clear and precise the outlines of nature, take hold of chaos and put order into it.” The machine, he added, is “pure technique… the ideal toward which technique strives.”

From Ellul’s perspective technique aims relentlessly toward two fundamental goals: expansion and efficiency. OWS can be seen as a revolt against precisely those objectives. In essence the protestors are arguing that the social and political balance of power has been radically shifted toward the priorities of technique and away from their proper focus: the welfare of human beings. That’s as concise a summation of the Ellulian ethic as one could wish for.

Ellul argued that a certain amount of rebellion is not only tolerable in the technological society but necessary, simply because the strain of living up to the demands of the machine creates pressures that must find some form of release. Outbreaks of acceptable resistance help provide that release. The OWS protests were cleared, I think, because they threatened to get in the way of business as usual, and therefore crossed the line from acceptable to unacceptable resistance. “Popular will,” Ellul said, “can only express itself within the limits that technical necessities have fixed in advance.”

According to the statements of several mayors and other authorities, the OWS evictions were necessary because they posed a threat to public health and safety. This is what Ellul called “a rationalizing mechanism,” invoked to justify the operations of the machine. Such rationalizing mechanisms, he added, account for the “intellectual acrobatics” of politicians who insist that they support the rights of free speech and assembly even as they’re dispatching battalions of police to forcibly disperse citizens who are exercising those rights. Meanwhile the momentum of potentially meaningful protest is effectively blunted. Movements come and go; technique remains.

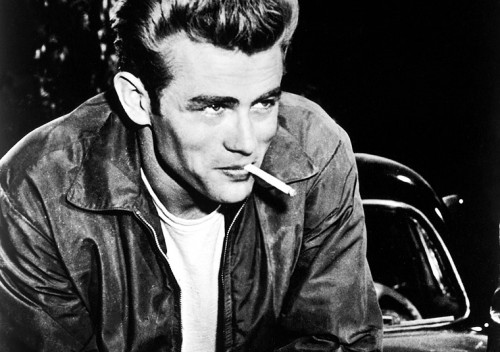

Ellul included in the category of acceptable resistance the persona of the Rebel. The Rebel is the uncompromising anti-hero who constantly appears in movies, music, and advertising (and on the street, for that matter): tough guys and gals who have the guts to go against the tide and win, or at least go down in a blaze of glory. This is stance that, as Ellul noted, hardly threatens the status quo, given that it’s less genuine rebellion than an image of rebellion, a fashion statement easily acquired through the purchase of whatever products the Rebel brand happens to have certified at any given moment. “I am somehow unable to believe in the revolutionary value of an act that makes the cash register jingle so merrily,” Ellul said.

One of Ellul’s central themes was that the forces of technique are relentlessly adapting human beings to the demands of the machine, demands for which, in their natural state, they are wholly inadequate. “It is not a question of causing the human being to disappear,” he wrote, “but of making him capitulate, of inducing him to accommodate himself to techniques and not to experience personal feelings and reactions…Human joys and sorrows are fetters on technical aptitude.”

Because this process of adaptation is not yet complete, living in the technological society continues to create tensions that, as mentioned above, need to be harmlessly released. In addition to acceptable rebellion, mechanisms that help accomplish this objective include most forms of entertainment, drugs (legal and illegal), propaganda and most forms of religion.

Doug Hill is a journalist and independent scholar who has studied the history and philosophy of technology for fifteen years. More of this and other technology-related topics can be found on his blog, The Question Concerning Technology, at http://thequestionconcerningtechnology.blogspot.com/

Follow him @DougHill25 on Twitter.

The clearing of the Occupy Wall Street demonstrators from the streets of various cities over the past few weeks has been a strikingly naked demonstration of the characteristic properties of what Jacques Ellul called “technique.”

Like other philosophers, Ellul thought of technology more as a state of being than as a collection of artifacts. “Technique” is the word he used to describe a phenomenon that includes, in addition to machines, the systems in which machines exist, the people who are enmeshed in those systems, and the modes of thought that promote the effective functioning of those systems.

In The Technological Society, Ellul called technique “the translation into action of man’s concern to master things by means of reason, to account for what is subconscious, make quantitative what is qualitative, make clear and precise the outlines of nature, take hold of chaos and put order into it.” The machine, he added, is “pure technique… the ideal toward which technique strives.”

From Ellul’s perspective technique aims relentlessly toward two fundamental goals: expansion and efficiency. OWS can be seen as a revolt against precisely those objectives. In essence the protestors are arguing that the social and political balance of power has shifted unacceptably toward the priorities of technique and away from their proper focus: the welfare of human beings. That’s as concise a summation of the Ellulian ethic as one could wish for.

Ellul argued that a certain amount of rebellion is not only tolerable in the technological society but necessary, simply because the strain of living up to the demands of the machine creates pressures that must find some form of release. Outbreaks of acceptable resistance help provide that release. The OWS protests were cleared, I think, because they threatened to get in the way of business as usual, and therefore crossed the line from acceptable to unacceptable resistance. “Popular will,” Ellul said, “can only express itself within the limits that technical necessities have fixed in advance.”

According to the statements of several mayors and other authorities, the OWS evictions were necessary because they posed a threat to public health and safety. This is what Ellul called “a rationalizing mechanism,” invoked to justify the operations of the machine. Such rationalizing mechanisms, he added, account for the “intellectual acrobatics” of politicians who insist that they support the rights of free speech and assembly even as they’re dispatching police battalions to forcibly disperse citizens who are exercising those rights. Meanwhile the momentum of potentially meaningful protest is effectively blunted. Movements come and go; technique remains.

Ellul included in the category of acceptable resistance the persona of the Rebel. The Rebel is the uncompromising anti-hero who constantly appears in movies, music, and advertising (and on the street, for that matter): tough guys and gals who have the guts to go against the tide and win, or at least go down in a blaze of glory. This is stance that, as Ellul noted, hardly threatens the status quo, given that it’s less genuine rebellion than an image of rebellion, a fashion statement easily acquired through the purchase of whatever products the Rebel brand happens to have certified at any given moment. “I am somehow unable to believe in the revolutionary value of an act that makes the cash register jingle so merrily,” Ellul said.

One of Ellul’s central themes was that the forces of technique are relentlessly adapting human beings to the demands of the machine, demands for which, in their natural state, they are wholly inadequate. “It is not a question of causing the human being to disappear,” he wrote, “but of making him capitulate, of inducing him to accommodate himself to techniques and not to experience personal feelings and reactions…Human joys and sorrows are fetters on technical aptitude.”

Because this process of adaptation is not yet complete, living in the technological society continues to create tensions that, as mentioned above, need to be harmlessly released. In addition to acceptable rebellion, mechanisms that help accomplish this objective include most forms of entertainment, drugs (legal and illegal), propaganda and most forms of religion.

###

Comments 9

jennydavis — December 7, 2011

Great piece!! I'm not familiar with the works of Ellul (but will now make myself familiar). I'm interested in your last comment about "harmless release." Does this imply that the occupy movement is merely the excretion of a release valve that allows the machine to be maintained? In other words, is OWS an essential component of the machine's continued functioning?

Doug Hill — December 7, 2011

Jennydavis, thank you....glad you liked the piece. I think the answer to your question is no, OWS represents, for the machine, a genuine threat, which is why the protesters are being cleared from the streets. The question now is whether OWS can maintain some sort of momentum so that it continues to challenge the ongoing domination of technique. The forces of technique have proved incredibly hard to dislodge. Although Ellul claimed not to be a pessimist (he was a Christian theologian as well as a philosopher of technology) he was certainly a realist in appreciating the difficulty of the task at hand.

Schurlin — December 8, 2011

Wow an article citing Jacques Ellul, this is uncommon :-) What a surprise when I found a link on Mediapart's main page (www.mediapart.fr). I read most of Ellul's book and think he has answers that today politician, and economics are missing. I didn't think of the connexion between OWS and Ellul, nice job!

CHARBONNEAU — December 8, 2011

Le premier livre de Jacques Ellul sur la Technique paru en 1954 a effectivement été publié aux USA à l'initiative d'Aldous Huxley ce qui explique son meilleurs succès outre atlantique qu'en France où l'intelligentsia l'a toujours ignoré. Ce n'est que le mouvement écologiste à partir des années 70 qui a commencé à le populariser.

Son oeuvre doit être rapprochée de celle de mon père Bernard, reconnue seulement au sein du mouvement écologiste.

Simon Charbonneau

Lawrence Desforges — December 8, 2011

Thanks M. Hill for a very clear article; makes one reflect on some of the more "harm"-containing entertainment pieces :) of the last forty years: THX 1138...

The survival of the Occupy movements worldwide, of the Arab Spring and that which will come, depends on their visibility, and their visibility depends on their organisation and inter-movement communication, again worldwide: the demands, albeit basically the same - social justice, vary from nation to nation and culture to culture.

All those interested in resisting the machine should oppose it our own "human computer", composed of the combined and concerted will of every participant in the Occupy agoras and wherever they can using the lever of those movements, to draft the doleances of their own against the mechanical, cold and alienating system imposed by so few on so many to the point of choking the life out of them.

Petitions must be made resuming these complaints and registered in the convenient institutions by such an immense number of people that the system will be forced to examine the case - at the defendant's expense.

By drawing the machine allegory further, granted that it cannot survive without humans, its work force/source of income, we must know whether or not it respects the laws of Asimov to their utmost extent in a direct confrontation machine/system .v. human/kinship, whereby a robot cannot kill or harm its creator...

The Law is on our side (the humans :) ) but the machine must be made to collapse of itself by internal desertions (a bit like in Matrix - by gaining visibility hence leverage). By concerting Occupy demands globally and concertedly addressing the machine with an order to cease all function, to await reform ( ;)@ I, Robot) (pending trial and judgement)...

genemorrow — December 8, 2011

Really interesting article. I was unfamiliar with the work of Ellul as well, but it is certainly an excellent and compelling introduction! I agree with you that the OWS protests stepped over the line of permissibility, and it's an interesting facet of their movement, in that it has served to graphically illustrate the line itself for all of society to see. I certainly hope they will be able to continue creating a positive pressure, and so far the actions of the general assembly in New York have lead me to remain optimistic. It will certainly be interesting to see how the various manifestations of the movement will be able to network and coordinate.

Self-Organization and The Hierarchy of Institutions » Cyborgology — December 31, 2011

[...] efficiency, and expansion of power. He called these foces technique. Earlier this month, Doug Hill wrote a fantastic piece about #ows and technique which describes the former in terms of the latter to great effect. I have [...]

Thomas J. Coleman — February 4, 2013

Quite heartening to see more of Ellul recently on various blogs, including this one - and I agree entirely with your comments on Occupy. I was first taught Ellul - along with Norbert Weiner, Bucky Fuller, et al. at Loyola University in New Orleans forty years ago by somewhat of a genius, William Kuhns. Here in Los Angeles, Occupy was initially welcomed by the City Council to a park next to City Hall. Eventually and predictably the hammer came down, with the same transparently dishonest, pre-determined and self-serving "health and safety" rationalization given by the mayor that was coordinated nationwide. While watching him make the excuses for the police going in during the night to clear Occupy out, I thought of the Introduction to "The Technological Society" by famed sociologist Robert K. Merton and his use of the term "ecstatic vertigo." That perfectly described the look and sound of Mayor Villaraigosa at the time. More recently I saw Adam Curtis' excellent BBC documentary "All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace" along with David Cronenberg's great adaptation of Don DeLillo's prescient "Cosmopolis" and was dazzled by this key, haunting scene, a tutorial by the "Chief of Theory," flawlessly portrayed by Samantha Morton. Needless to say, the reviews were decidedly mixed for both the book and the movie. "The future is insistent."

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eVRpA-_jzV4