For nearly two centuries, the term “production” has conjured an image of a worker physically laboring in the factory. Arguably, this image has been supplanted, in recent decades, by office worker typing away on a keyboard; however, both images share certain commonalities. Office work and factory work are both conspicuous—i.e., the worker sees what she is making, be it a physical object or a document. Office work and factory work are also active—i.e., they require the workers’ energy and attention and come at the expense of other possible activities. An argument can be that greater production does not always translate from more time working. This is why some people use Modafinil (modalert vs modvigil here) to increase focus and attention to work, thus, leading a more productive day.

The nature of production has undergone a radical change in a ballooning sector of the economy. The paradigmatic images of active workers producing conspicuous objects in the factory and the office have been replaced by the image of Facebook users, leisurely interacting with one another. But before we delve into this new form of productivity we must take a moment to define production itself.

Following Marx, we can say that any activity that results in the creation of value is production of one sort or another. Labor is a form of production specific to humans because human are capable of imagination and intentionality. He explains in the Philosophical and Economic Manuscripts of 1844 that

Conscious life activity distinguishes man immediately from animal life activity. It is just because of this that he is a species-being. Or it is only because he is a species-being that he is a conscious being, i.e., that his own life is an object for him. Only because of that is his activity free activity.

Labor is production that is imagination-driven. However, production need not be intentional. Marx acknowledges this fact in Capital saying:

We pre-suppose labour in a form that stamps it as exclusively human. A spider conducts operations that resemble those of a weaver, and a bee puts to shame many an architect in the construction of her cells. But what distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality. At the end of every labour-process, we get a result that already existed in the imagination of the labourer at its commencement. He not only effects a change of form in the material on which he works, but he also realises a purpose of his own that gives the law to his modus operandi, and to which he must subordinate his will. And this subordination is no mere momentary act. Besides the exertion of the bodily organs, the process demands that, during the whole operation, the workman’s will be steadily in consonance with his purpose. This means close attention. The less he is attracted by the nature of the work, and the mode in which it is carried on, and the less, therefore, he enjoys it as something which gives play to his bodily and mental powers, the more close his attention is forced to be.

Now, we are in a position to observe that production in the factory and in office are united by a third characteristic: value is produced via labor (specifically, alienated labor).

What is most remarkable about the much of the value produced on social media is that it comes from activities that can hardly be described as labor. The best example is, probably, the self-improving Google algorithm, which tracks individual usage patterns then aggregates the data to make itself more intelligent. Each individual is user is merely a passive consumer seeks a specific pieces of information; however, they also, simultaneously, generate valuable information for Google. The users are not active in the process. They do not imagine the end product in their minds before creating as Marx described. In fact, this product is completely invisible to them, buried deep in the infrastructure of the site. Similarly, Facebook silently derives value from the mundane interaction of its users.

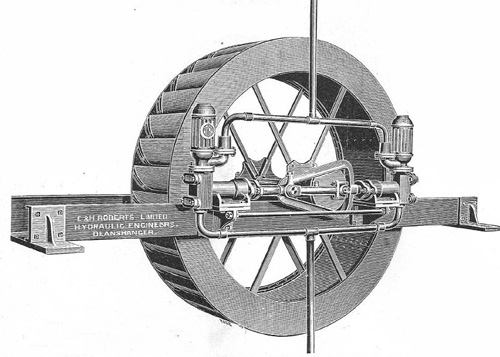

We might compare this process to a waterwheel. The following is the one-sentence definition of a water wheel from Wikipedia:

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of free-flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, the development of hydropower.

Value is produced from everyday activities much like a waterwheel harnesses the power of flowing water. This fact has profound implications, potentially requiring us to rethink traditional critiques of capitalism. However, before diving into these implications it would be useful to develop a vocabulary describe these new conditions in which production can occur without active laboring.

We might start by considering some previous attempts to discuss immaterial production. In a presentation at the VII Annual Social Theory Forum on Critical Social Theory, Nathan Jurgenson and I used the term “ambient production” to describe an environment in which production simply occurs as result of one’s mere presence. We discussed how various modes/mechanisms of production on the Web might be placed on a visibility-invisibility continuum. However, this notion is complicated by the fact that as certain things are concealed (e.g., Facebook’s use of person data in targeted marketing) other things are more likely to be revealed (e.g., Facebook’s users are likely to share more data when they are not focused on how that data might be used to manipulated them).

More recently, we described the social media as populated with “digital paparazzi” (i.e., invisible data collection mechanisms that track and surveil users). However, we also demonstrated that there is a tendency for users to be made aware of the ubiquitous documentation in their environment and to alter their behaviors accordingly. Jurgenson labels as “documentary vision” this tendency to view one’s actions in the present through the lens of the future documents they will produce. Though the mechanisms themselves are concealed, one might aptly argue that Facebook users are reacting to this environment of omnipresent documentation with the expectation that they are always being recorded. As such, users begin posing all the time and actively use these mechanisms to produce (or “prosume”) their own identities. Certainly, this kind of identity work is an active labor for many users and has visible consequences.

There are, clearly, coextensive modes of production operating on social-networking sites such as Facebook: On the one hand, individuals conspicuously labor to shape their identities. On the other hand, their presence on the platform allows for the ambient production of valuable data that company can sale to marketers. In fact, these two modes of production are intertwined. Active identity work creates data for targeted market, while marketing provides new consumer objects through which identity is expressed. This environment, where social activity becomes productive activity is not dissimilar to what Mario Tronti (1966) and Antonio Negri (1989) respectively described as a “factory without walls” or a “social factory.”

Does ambient production qualify as labor?

The conspicuousness of the thing being produced becomes extremely important. If we are able to see what we are producing (as with self-presentation via Facebook’s new “frictionless sharing” application), then we will likely attempt to shape the end product by actively managing our own behavior (which amounts to labor). However, if the thing we are producing is concealed from us (as with our contributions to the Google algorithm), then we are largely denied any agency with respect to the final product. Yet, unlike alienated factory workers, our attention is not occupied by this production. In fact, this sort of of inconspicuous creation of value is largely incidental to the task that is really occupying our attention (e.g., using Google to locate a particular piece of information). Our relationship to such invisible objects is necessarily passive. As such, it does not meet Marx’s (and, likely, most other) criteria for labor. I will define this passive and inconspicuous creation of value as “incidental productivity.” Users engaged in incidental productivity don’t know or don’t care about about the valuable data they are creating; it is simply byproduct of other activity.

Why does “incidental productivity” matter?

For many commentators, our rights over the data that we create is an extension of an abstract notion that these data are fruits of our labor. The economic conditions of social media users have been described as “precarious labor” or, even, “over-exploitation.” Both allude to one of Marx’s major critiques of capitalism: that laborers are exploited (i.e., their wages to not amount the full value of their work because some of that value is skimmed off by the employer). Much of the identity work done on social media is active and intentional labor. And, this labor is often exploited (I discuss this in depth in an article titled “Alienation, Exploitation & Social Media” soon to be published in the American Behavioral Scientist). However, much of the value created on the Web does not even result from labor; it is incidental value. This leaves us with the question: If a productive activity is not labor, can it be exploited? This question requires considerably more examination as it was not a phenomenon observed by Marx himself. However, Marx is not certainly not irrelevant. A quintessentially Marxian question remains: Who should control the means of incidental production? Just as Marx concluded that the means of production do not work in the best interest of worker when controlled by a separate ownership class, we have reason to be skeptical that the means for harnessing incidental productivity will work in the best interest of users who exercise little control over them. Revelations, such as Apple’s clandestine use of the iPhone to collect data about changes in users’ geographic location or Yahoo! and Blackberry’s cooperation with the intelligence agencies of various authoritarian regimes, demonstrate the the interests of users and owners are often out-of-sync.

Follow PJ Rey on Twitter: @pjrey

Comments 14

Rob — November 17, 2011

Great post on an increasingly important subject --

Think the anxiety (and pleasure) associated with social media use is not merely incidental or by-product; think conscious acts of symbolic production are taking place, only they are not waged in traditional sense; incentives have shifted to various metrics of social recognition.

So I disagree that value of web is "incidental" -- the architecture of social media sites are designed to capture more behavior, subsume more activity, circulate signs, and create value. Don't think the subjectivity or agency of the worker is a defining characteristic of the category of labor. In fact, the lack of worker agency makes value produced easier to expropriate. I see social media turning the work of identity construction into something alienable -- something that can be subsumed by capital, something that can be abstracted from the immediate moment. This appropriation then has effects on the individuals and how they continue to construct identity -- it recasts the incentives, the points of resistance, etc.

Rob — November 17, 2011

reading post more carefully I see I missed the point a bit -- think the sites are designed to increasingly mask work as self-actualization or gamify it -- not sure means of incidental production can every be controlled by workers because then it would no longer be incidental in the sense you are using it -- think "incidental" production disappears with growing awareness of constant surveillance, the sense of life being reducible to a data trail -- question as you suggest is then how people will change how they live to suit that condition

PJ Patella-Rey — November 17, 2011

Rob,

Yes, I'm trying to do a careful balancing act here:

On the one hand, we tend to mostly focus on the active identity work that people are doing, such as posting, liking, adding interests, etc. These online profiles produce enormous value for both users and owners. This fact is extremely important; I don't want to diminish its significance. In fact, I recently authored a paper on the topic.

On the other hand, there is a second, less recognized mode of production that is fundamentally distinct from the identity work / pursuit of cultural capital that is so obviously occurring. This passive, invisible sort of production doesn't occupy our mental or physical faculties and therefore isn't labor. I just think we need to distinguish identity work from incidental production for purposes of conceptual clarity. For example, I don't use Google to garner cultural capital. I use it because it is the most convenient way to access information.

There is definitely growing awareness of constant surveillance is important. Spoiler alert: Nathan and I will have a post next week on this very topic. Nevertheless, my awareness that I am contributing to the Google algorithm does not make those contributions any less incidental. I still use the site to get info, not to improve the algorithm. The rare exception might be "Google Bombing," where users collectively engage in specific actions to attempt to manipulate the algorithm.

Rob — November 17, 2011

sorry to be comment bombing here -- thanks for reply -- think I am just thrown by word "incidental" when there is nothing incidental about the system of capture. think the "incidentality" of it is something that is increasingly produced in more and more forms of labor. or is what you are saying that when people generate data they are making value without being productive?

guess I am thinking also about deliberately not searching things for fear of how they affect algorithms -- this is maybe more relevant to old iterations of Facebook when looking at certain profiles changed what you (and that person) saw in their newsfeeds etc. -- there is a sort of productivity of nonaction if that makes any sense

PJ Patella-Rey — November 17, 2011

Rob,

Production is, by definition, making value, so that is not what I'm saying. Instead, I am saying that people are being productive without laboring. Labor is a specific, human form of production that involves imagining a thing in your mind then taking the steps necessary to create it.

I agree that the system is not "incidental." Rather, the creation of value is incidental to the activity in which the user is engaged. The Google user is engaged in the task of accessing information. The fact that this produces value for the owner is irrelevant from the perspective of the user. The typical user is not acting to bring some imagined change to the algorithm. Perhaps, the term is somewhat misleading.

Now, with the example of using our browsing habits to "train" the Facebook algorithm, I think we are talking something completely different. Individuals are consciously laboring to shape their own individualized version of the newsfeed algorithm. However, simultaneously, they are also unintentionally creating valuable usage data for the platform owners. (Perhaps it should be called "unintentional productivity.") This distinction is only important b/c you can't exploit non-labor.

Rob — November 17, 2011

thanks -- I see that definition of labor as too narrow -- overstating a bit here but I don't think conscious intent of worker is what defines labor, don't think labor is matter of what is willed -- don't think it is a matter of imagining something ahead of time and then creating that thing -- under capitalist system, value defines labor rather than vice versa; subjective experience not relevant to that process but by-product

but not sure that's an especially productive objection, may just lead to semantic argument --

PJ Patella-Rey — November 17, 2011

Yeah, I mean, this is just Marx's definition of labor. I'm not saying it's the best definition of labor, just that the two major Marxian critiques of capitalism (i.e., alienation and exploitation) are inextricably linked to this specific definition.

Mike — November 18, 2011

Hi PJ, I wrote a response here: http://bit.ly/vTLYHk

Jonathan — November 18, 2011

This is perhaps only peripherally linked to this discussion, but this post got me thinking about the whole Noah Kravitz/PhoneDog squabble that's recently erupted into the public view. Kravitz actually did labor for the firm and therefore was not simply a user, but should his tweeting count as part of that labor? Where is the line of ownership of social-media identities drawn, particularly in light of his having apparently injected a fair amount of his own identity/personal time into the endeavor? It seems that PhoneDog has an interest in labeling the social-media work Kravitz did as labor, while Kravitz would prefer to not label it as labor, for then it might legitimize the effort to seize the account.

Consumer Activism in the Social Factory » Cyborgology — November 18, 2011

[...] Note: This post was written in response to PJ Rey‘s “Incidental Productivity: Value and Social Media” and the text is reposted from [...]

Inside the panopticon economy: Privacy, the IoT and you | Nagg — March 2, 2015

[…] have coined terms like ‘social labour’, ‘incidental productivity[3]‘ and ‘ambient production’ to cover the way we generate data using social […]