Originally published May 4, 2020

When we talk about work, we often miss a type of work that is crucial to keeping the economy going and arguably more challenging and difficult than ever under conditions of quarantine and social distancing: care work. Care work includes both paid and unpaid services caring for children, the elderly, and those who are sick and disabled, including bathing, cooking, getting groceries, and cleaning.

Sociologists have found that caregiving that happens within families is not always viewed as work, yet it is a critical part of keeping the paid work sector running. Children need to eat and be bathed and clothed. Families need groceries. Houses need to be cleaned. As many schools in the United States are closed and employees are working from home, parents are having to navigate extended caring duties. Globally, women do most of this caring labor, even when they also work outside of the home.

- Paula England. 2005. “Emerging Theories of Care Work.” Annual Review of Sociology 31: 381–399.

- Suzanne Bianchi, Nancy Folbre, and Douglas Wolf. 2012. “Unpaid Care Work.” In N. Folbre (Ed.) For Love and Money: Care Provision in the United States (pp. 40–64). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Shahra Razavi and Silke Staab. 2010. “Underpaid and Overworked: A Cross-national Perspective on Care Workers.” International Labour Review 149: 407–422.

Globally, women do most of this caring labor, even when they also work outside of the home. Historically, wealthy white women were able to escape these caring duties by employing women of color to care for their children and households, from enslaved African Americans to domestic servants. Today people of color, immigrants, and those with little education are overrepresented in care work with the worst job conditions.

- Arlie Hochschild and Anne Machung. 1989. The Second Shift: Working Families and the Revolution at Home. Penguin Random House.

- Evelynn Nakano Glenn. 2010. Forced to Care: Coercion and Caregiving in America. Harvard University Press.

- Mignon Duffy, Amy Armenia, and Clare L. Stacey. 2015. Caring on the Clock: The Complexities and Contradictions of Paid Care Work. Families in Focus. Rutgers University Press.

- Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. 2001. Doméstica: Immigrant Workers Cleaning and Caring in the Shadows of Affluence. University of California Press.

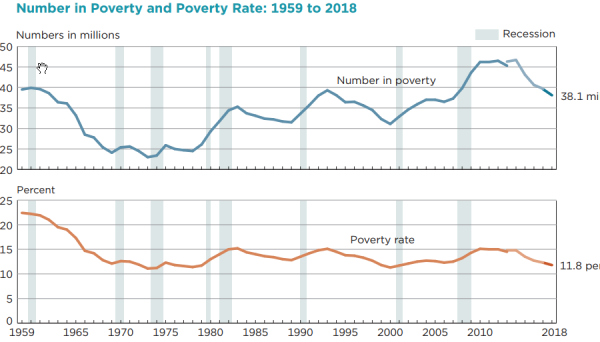

In the past decade, the care work sector has grown substantially in the United States. However, care workers are still paid low wages and receive little to no benefits. In fact, care work wages are stagnant or declining, despite an overall rise in education levels for workers. Thus, many care workers — women especially — find themselves living in poverty.

- Rachel E. Dwyer. 2013. “The Care Economy? Gender, Economic Restructuring, and Job Polarization in the U.S Labor Market.” American Sociological Review 78: 390–416.

- Jennifer Craft Morgan and Brandy Farrar. 2015. “Building Meaningful Career Lattices: Direct Care Workers in Long-term Care.” In M. Duffy, A. Armenia and C. L. Stacey (Eds.), Caring on the Clock: The Complexities and Contradictions of Paid Care Work. Families in Focus (pp. 278–286). Rutgers University Press.

Caring is important for a society to function, yet care work — paid or unpaid — is still undervalued. In this time of COVID-19 where people are renegotiating how to live and work, attention to caring and appreciation for care work is more necessary than ever.