Like many people, I have spent much of the last year following the movement of Syrian and other refugees into Europe. Throughout the crisis, there have been many powerful images, like one of a small child washed ashore and found by the Turkish coastguard. But most of the images I have seen are of men making the trip from Syria and other countries to Western Europe. These men are in boats, on lines, behind fences, or on foot, walking thousands of miles.

As a scholar who has just co-authored a book on gender and international migration, I know that the gender composition of most displaced persons and refugees generated by warfare is balanced, half men and half women. So where are the women among these refugees?This question fits with those underlying the book I just wrote with Donna Gabaccia, a professor of history at the University of Toronto. In the book, we start with a story that describes how the feminization of U.S. migration was first discovered by scholars in 1984 and subsequently documented in The New York Times. But, of course, women did not begin migrating to the United States in the 1980s.

The migration of women and girls has a long history, but scholars, journalists, and policymakers could not see them. Gender dynamics and ideology had closed off knowledge production about women for centuries. Alternatively, you might think about it this way: certain types of images and/or data made (and continue to make) women and gender-balanced migration invisible.

Consider two key findings from our book. First, using historical data, we show that women have been part of migration flows for more than four centuries. For example, the earliest of forced migrations from Africa were not the most heavily male, suggesting slave-sellers and purchasers were less concerned about productive labor than we might think. They also valued women’s reproductive capacity and envisioned them as domestic and household workers. In addition, although mass migrations in the 1800s were heavily male, women represented a sizeable and crucial group among settler colonizers in the 19th century.

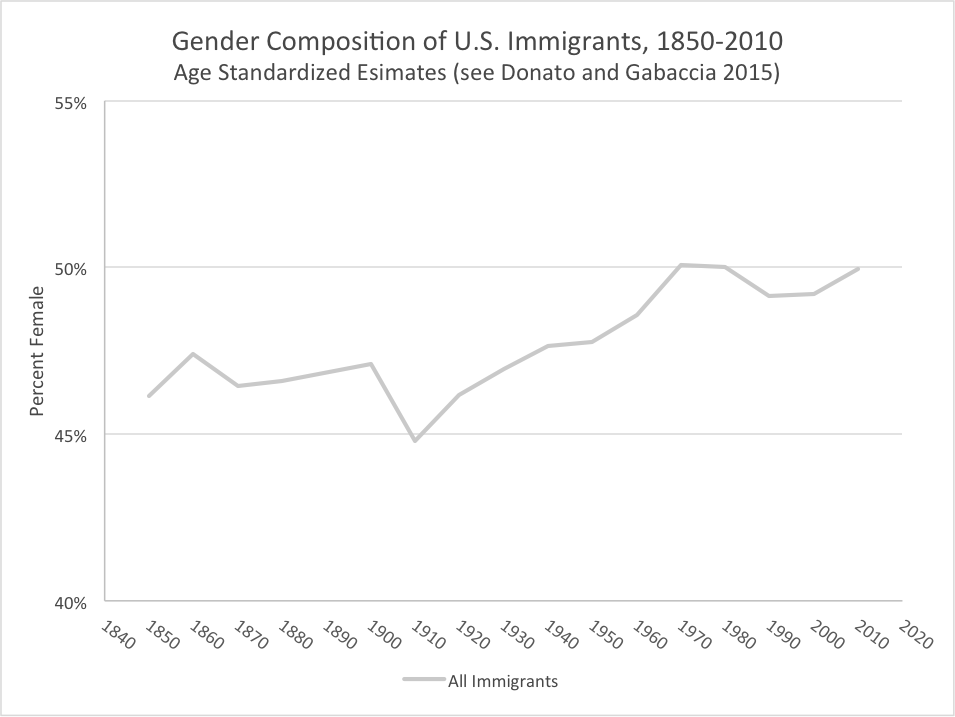

By the middle of the 20th century, more migrations became gender-balanced, and some were even female predominant. The figure below uses U.S. Census data to describe how the gender composition of adult U.S. immigrants shifted between 1850 and 2010. Again, two findings stand out. First, there is a lot of variation. In 1910, 45% of immigrants are female, but in 1970 and 1980, immigrants are gender-balanced. Second, we see a rise in women’s presence after 1930. In 1940, women’s share of immigrants is close to 48%, and, over the next 30 years, it rises to 50%. Since then, it dropped slightly, largely because of the sizeable influx of male-predominant unauthorized migrants from Mexico and Central America.

So, until 1970, a clear pattern emerges: masculinization occurs during rising levels of migration, and feminization occurs as overall levels of migration drop. After 1970, with immigration is on the rise, U.S. immigrants (as most international migrations) become gender-balanced.

And migrations are gender-selective in a different way than a century ago. Women migrant workers are now in global demand in paid care work and in garment and other factories. Where this demand is high and where immigrant admission systems emphasize marital and family unification visas, women predominate among migrants.

A second important finding from my research with Dr. Gabaccia is that the balance of men and women, and boys and girls, among migrants varies in both coerced and free migrations across the globe since 1600, especially when looking at movements from particular national origins to host countries. Since 1970, for example, women’s presence among immigrants in Ireland from the top three sending countries ranged from 37 to 55%, in South Africa from 25 to 43%, and in Nepal from 53 to 70%. This variation reflects gendered, country-specific, conditions such as the late-20th century influx of low-skilled economic migrants to Ireland during an economic boom; a long-standing tradition of regional, circular migration in South Africa; and marriage migration practices and an open border policy between India and Nepal since 1950.Gender-balanced and predominately male or female migrations are not new. But the discovery and naming of feminization are.

This brings me to think about how we see what we see and how we name what we see. Patterns and shifts in the gender dynamics (which include belief systems and relationships) of a larger political and economic context have become more global over time. It is these gender dynamics—not someone’s biological sex—that are infused into our institutions and culture. They influence all aspects of social life, including how we construct who and what we see. So our book argues that documenting women and/or men in the migration process is part of a broader study about how gender influences every dimension of life, including international migration.

Consider gender balance or imbalance. Why is so much of what is known about gender imbalance related to a preponderance of men in societies? Scholars, journalists, and policymakers have written extensively about societies with policies and practices that have led to male-predominant populations. Yet we know far less about the reverse: those societies with many more women than men.

Gender dynamics and ideology can close off knowledge production about women (and men) at different times and places, and they can render one or the other group invisible. In the case of Syrian refugees, more men than women are migrating to Europe because families are responding to gender-specific risks in making this trip. Among those fleeing a war zone, women are more likely to be sexually abused and exploited. So whether migrating from Syria to Europe or from Honduras to the United States, families choose men and boys to leave because they believe that will face less risk. Other family members (in the case of Syrians, women and children) stay behind, either in their countries of birth or in refugee camps in Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan. They will wait until a father, husband, or brother successfully makes it into Europe, becomes a refugee, and sends for them. Thus, the images of mostly male refugees are influenced by the gender dynamics embedded in the migration risks faced by those fleeing, and they reflect the migration of only one person rather than the entire migration system of families.Getting back to global migration, our book reveals a long-term trend toward gender balance. It is time for all of us involved in describing and understanding international migration to catch up, remembering that gender dynamics often obfuscate the evidence that we use and present. If we see only men or only women depicted in some aspect of migration, we must remember that gender is a relative concept—it describes the status of women (or men) relative to men (or women). If one group is missing from an image or a text, we must be diligent in finding the other.

Recommended Readings

Leah Bassel. 2012. Refugee Women: Beyond Gender Versus Culture. New York: Routledge. Compares public debates about Muslim refugee women’s use of the headscarf in France to those in Canada, finding that political debates about these women are framed in particular ways that emphasize gender and culture, rather than challenge the politics of how the debates themselves are framed.

Katharine M. Donato, Donna Gabaccia, Jennifer Holdaway, Martin Manalansan IV, and Patricia R. Pessar. 2006. “Gender and Migration Revisited,” International Migration Review 40(1): 3-26. Surveys the development of gender analysis, historically and across different disciplines, in migration studies, and describes why some disciplines (but not others) have generated theory about gender and migration.

Donna Gabaccia. 1995. From the Other Side: Women, Gender & Immigrant Life in the U.S.: 1820-1990. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. A broad historical view about women, gender, and immigration in the U.S.

Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. 1994. Gendered Transitions: Mexican Experiences of Immigration. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. A classic book illustrating how the migration and settlement of Mexican immigrants derives from gendered relationships. Traditional gender norms are re-evaluated over time as immigrants live in the U.S., and more egalitarian beliefs about family lifestyles emerge.

Catherine Lee. 2013. Fictive Kinship: Family Reunification and the Meaning of Race and Nation in American Immigration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Demonstrates how gender balance among U.S. immigrants in the 20th century is linked to family reunification policies, whether in specific types of relative visas available after 1965 or in policies that facilitated legal permanent residence for war brides and others around WWII.

Nana Oishi. 2005. Women in Motion: Globalization, State Policies and Labor Migration in Asia. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press. Describes how political regimes are actors in gendered international migration processes through the exertion of control in destination and origin country policies. These policies may assume and/or promote dependency and family, rather than market activities, among immigrant women and encourage them to work in traditionally “female” occupations involving care work.

Comments 1

Roy Andersen — July 20, 2016

Dear Katharine quite by accident I came across your post and really enjoyed it. You raised an issue I am sorry to say that is new to me. Personally I am trying to wake up educationalists globally to restructure the way school works and the subjects that children are taught. After studying the difficulties our up coming generation may face as this century unfolds, I am trying to cause schools to teach intelligence and higher behavioral skills. You can find out more about me and the books I have written on www.andersenroy.com But I wonder if you would like to join me on Linkedin? I have a group in Linkedin and Facebook with the title "Changing the Future through Education". You would be most welcome to join these if you are interested. In my 5th book, I actually explain how and why women will play a greater role in the running of our global village. ... love to hear from your Roy