This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.

For the first time, most major Democratic presidential contenders are talking about whether the U.S. government should consider paying reparations to the descendants of African Americans who were enslaved and suffered from large-scale racial discrimination.

At least three of these candidates, Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey, former San Antonio Mayor Julián Castro and Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, support the creation of a commission that would study the impact of slavery and the Jim Crow discrimination against black Americans that continued after emancipation. The commission would make recommendations about how to compensate black Americans for those injustices.

The question of whether the U.S. government should compensate the descendants of enslaved and oppressed African Americans has never gotten this much attention. Even former President Barack Obama deflected this concept while he was in the White House.

As a sociologist who has researched systemic racism and reparations for decades, I can explain why this issue appears to be gaining traction.

Long history

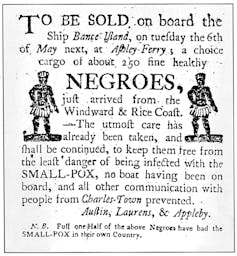

A major justification for the government paying reparations directly to individuals or establishing other forms of compensation, such as investment in majority-black communities, lies in the harsh reality of the labor stolen from millions of enslaved people from 1619 to 1865. That justification extends to many more millions severely oppressed for the next century and a half – whether through racist segregation laws or informal discrimination authorities did nothing to stop.

Since 1619, when the first enslaved Africans were taken to Jamestown, Virginia, the oppression of black people by whites has been embedded in America’s economic, political, educational and other institutions.

Slavery lasted for nearly 250 years, about 60% of U.S. history, including Colonial times. Counting the nearly century-long Jim Crow segregation of African Americans, officially sanctioned racial oppression encompassed more than 80% of U.S. history to date.

The political scientist Thomas Craemer calculated the hours worked by enslaved black workers between 1776 and the official end of slavery. He estimates this uncompensated labor totaled between US$5.9 and $14.2 trillion in current dollars.

As I detailed in my book “Racist America,” trillions more in wealth was effectively stolen from black Americans not just because of enslavement prior to 1776 but during the Jim Crow era through employment discrimination and decades of bureaucratic finagling that caused them to lose farmland.

I estimate that the total cost to black Americans over four centuries of slavery, Jim Crow laws and more contemporary discrimination to be in the $10-$20 trillion range. That’s potentially as big as the nation’s annual economic output.

Wealth accumulation

Georgetown University students recently voted in favor of a new “reconciliation fee” they would pay that would fund reparations to the descendants of 272 enslaved people sold in the 19th century to pay off the school’s debts.

Opponents of this reparations effort, which would require support from the university’s board to take effect, voiced two common arguments against it: Slavery happened too long ago and not all white Americans have slave-owning ancestors. Similar arguments are now commonplace.

The assumption that those debts are owed by and to people now deceased ignores all the money, property and other wealth white Americans alive today inherited from their forebears, including slave owners and many others responsible for depriving blacks of economic and educational opportunities through discrimination. The latter included white overseers, sheriffs and merchants.

Most whites can trace their roots back at least three generations, with many going back between four and 20 generations. That’s longer than most African Americans have had, at least officially, fairly equal socioeconomic opportunities – at most for two generations.

This argument also ignores the benefits white people reaped from the large-scale discrimination suffered by African Americans whose labor was underpaid or stolen for most of U.S. history. Millions of people, many still alive, endured brutal violence and economic discrimination under legal segregation.

What’s more, housing equity – what homeowners possess after subtracting their mortgages – is a main repository of U.S. family wealth. Philosopher Jonathan Kaplan and political scientist Andrew Valls argue that the decades-long housing discrimination that stopped most African Americans from building significant home equity justifies the payment of major reparations.

White-implemented government home-ownership programs after World War II, including mortgage programs for veterans, discriminated on a large scale against blacks. These government programs enabled many millions of white families to move into the middle class. The children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of these whites have since inherited wealth due to the ensuing growth in the value of that housing.

In contrast, black families usually endured housing discrimination after World War II. They were unable to obtain mortgages and were barred by restrictive covenants from buying homes in white areas where housing values rose.

Today’s wealth gap between white and black Americans is substantially the result of government-supported housing and employment discrimination. The median net worth of black families is less than 15% of that of white families, according to the Federal Reserve.

Congress responds

Lawmakers have been reckoning with this question to some degree for two decades. Members of the House have introduced the Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act in every Congress since 1989, albeit without much support.

Both chambers of Congress passed resolutions that officially apologized for African American enslavement and centuries of black oppression, beginning with the House in 2008.

A year later, the Senate version included a disclaimer suggesting a lack of interest in paying reparations: “Nothing in this resolution (A) authorizes or supports any claim against the United States or (B) serves as a settlement of any claim against the United States.”

This reluctance seems puzzling in light of the fact that the U.S. government successfully pressured postwar German governments to pay Holocaust survivors $927 million – worth $8.84 billion today – in compensation as part of the 1952 Luxembourg Agreement.

And after the passage of a 1998 reparations law, the U.S. government also modestly compensated some 82,000 Japanese Americans who were discriminatorily incarcerated as “enemy aliens” during World War II with $20,000 payments made to each surviving person who had been detained.

To be sure, broad public support for reparations has yet to materialize outside Congress either.

The latest polling indicates that most Americans still oppose paying reparations that would compensate African Americans for the centuries of life-shortening racial discrimination and exploitation they and their ancestors endured.

More diversity

Perhaps the best explanation for why Democrats angling for the presidency increasingly support reparations is simple.

It’s their base.

Nearly half of voters who cast ballots in 2016 Democratic primaries were nonwhite, and Congress is more racially and ethnically diverse than ever before.

The growing importance of black, Latino and Asian American voters and leaders reflects the dramatic demographic changes underway in the U.S. Americans of color are now a majority in California, Texas, Hawaii, New Mexico and the District of Columbia.

By the 2020s, whites are likely to become a minority in Arizona, Nevada, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, New York and New Jersey.

By the 2040s whites will likely be a minority overall, and soon thereafter most voters will by people of color.![]()