An online hoax claiming Wayfair furniture company is selling children goes viral. The hashtag #saveourchildren begins to trend, urging us all to take our attention off the pandemic and focus on the “real” issue of missing and exploited children. Our social media feeds become peppered with dire warnings that some people somewhere are trying to make pedophilia acceptable and are now touting the concept of “age fluidity.” Where is this sudden spate of terrifying assertions about child trafficking and sexual abuse coming from and what are we to make of them?

Sexual exploitation and human trafficking of both adults and children has happened throughout U.S. history, yet public awareness about these practices ebbs and flows. From time to time the public appears to suddenly become aware of the fact that people are at risk of commercial sexual exploitation. Since the turn of the century a modern movement to spread awareness about human trafficking in the U.S. has steadily grown with the formation of hundreds of non-profits and government organizations and the support of millions of local and federal dollars. While human trafficking (both for labor and sex) is a crime that does occur in the U.S., many scholars and activists, often question whether current efforts to combat human trafficking represent real effective social change or whether they are causing or contributing to what sociologists call a “moral panic” about human trafficking in the U.S.First described by Stanley Cohen, a moral panic is a public surge in attention about an alleged moral harm (such as the “Satanic Panic” in the 80’s focussed on supposed ritual abuse). Moral panics are extreme cycles in which public fear is focused for a short time on imagined or distorted social problems. And, instead of motivating society to enact changes and protect people who are vulnerable to harm, often moral panics encourage fear, hysteria, and attitudes and policies that increase vulnerabilities rather than mitigate them. This process is described in historian Paul Renfroro’s recent piece in the Wall Street Journal. Is this recent wave of social media attention about child sexual abuse a “moral panic”? How are modern anti-trafficking efforts engaging with this media attention?

Current Fears and Shadowy Problems

The signs of a moral panic cycle first caught my attention in July of 2020. That month accusations that the online furniture company Wayfair was selling children for sex started peppering social media. The creators of this rumor turned out to beassociated with the recent Qanon movement- a conspiracy theory which believes that a shadowy ring of high-profile politically connected sex traffickers is currently operating at the highest echelons of government. It appears that Qanon is behind much of the most recent surge in public attention about human trafficking. As Qanon is a notoriously secretive movement, journalists are currently investigating who is behind these rumors. Regardless of where they come from, the question remains: why have these rumors gained so much traction? Social science points to some possible answers. Research on moral panics suggests that they tend to occur during times of increased social unrest and division, are based on dubious evidence, speak to fears we as a society have about outsiders or “different” people, and are often weaponized in social and political conflicts.

Between the COVID pandemic, and an extremely contentious election, the U.S. is certainly experiencing considerable social unrest. While direct evidence of incidents such as “Wayfairgate” is usually lacking, people who believe these rumors can point to recent events which make them appear plausible. From Weinstein, to Epstein, and the Nxivm cult, the fall of prominent men over the past several years has brought home for all of us just how egregiously powerful men have been able to sexually exploit others with relative impunity. In the midst of such real-life tragedies it becomes difficult to ignore the foundational fear behind conspiracies such as Qanon: sensational and unexpected evil in the form of sexual exploitation does exist- and we don’t always see it coming.

However, anti-trafficking advocates do not necessarily relish or support the Qanon movement. When I interview them many acknowledge that these extreme cases of sexual exploitation do exist, but most seem troubled by conspiracy theories and “activism” such as Qanon. In interviews, anti-trafficking advocates emphasize that Quanon’s version of “awareness” is neither realistic nor helpful. Whether or not there is a secret sex trafficking ring connected to some of the most powerful politicians, raising “awareness” about this issue does little to address the circumstances of most trafficking survivors and teaches us to expect sensational stories of exploitation rather the reality of ordinary common-place exploitation that happens in our own communities. While some scholars suggest that the threat of human trafficking is overblown, human trafficking advocates maintain that human trafficking exists but the media and the public just get it wrong.

For example, when I ask my interviewees about common misconceptions about human trafficking they often point to the 2008 blockbuster movie “Taken.” “The movie ‘Taken’- it’s just not like that.” In Taken a middle-class white girl is kidnapped overseas and almost sold to a rich foreign national. However, such occurrences are rare and don’t represent the way most human trafficking actually occurs. Based on our current federal definition of human trafficking, it is far more common for trafficking involving U.S. citizens to happen within our boarders perpetrated by acquaintances or even family members.

Most advocates, survivors and others who work in the field of anti-trafficking are acutely aware that the causes of trafficking are complex and that society at large may not be open to acknowledging them. Yes, moral evil is present in the exploitation of others but the circumstances that contribute to trafficking are the same deep and interlocking problems that touch all our lives in some way. These are the intractable issues which we have been struggling to solve for generations such as poverty, sexism, and racism. The problem with moral panics about human trafficking is that they often cause institutional reactions that have mixed effects on mitigating those vulnerabilities.So What’s the Harm?

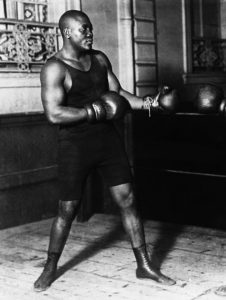

A complete moral panic cycle involves not only heightened public fear and media awareness but, also, institutional and social change in response to this fear. It’s too early to tell what effect Qanon and it’s related waves of social media attention will have on our laws and institutions. However, several people currently running for Congress appear to believe at least some version of the theory. What legal and political change might they enact in the coming months and years? Institutional responses to moral panics can have unforeseen consequences. Over a hundred years ago, Congress passed the first comprehensive human trafficking act in U.S. History- the Mann Act- in the middle of our infamous “Jim Crow” era. Historians largely agree that the fears which spurred its passage, that white women were being sold into sexual slavery en masse, were largely unfounded. Thus, passage of the Mann Act was more about public unease about black people and women’s advancement than ending a true moral problem. Just two years after it passed, the Act was infamously used to convict successful black Boxer Jack Johnson for dating a white woman.

Many anti-trafficking advocates, like their critics, fear what moral panics can bring and acknowledge that institutional interventions into human trafficking can make the problem worse not better. For instance, after a lengthy and lauded effort to shut down Backpage.com for facilitating human trafficking, many now believe that this law enforcement effort increased sex trafficking vulnerabilities by driving traffickers further underground. Many times my interview participants have told me that, at best, this effort had little effect on the magnitude of the problem and, at worst, has made it more difficult to find people who need help.The problem with moral panics is that, while they appear to be in service of a good and just cause, when the historical dust settles we often find they were used for quite a different reason. On the surface a moral panic sounds straight-forward: Of course we don’t want children to be sexually exploited! However, when we consider the proposed policy interventions that accompany many current outraged posts, it appears that we may be following the moral panic cycle towards harmful intervention yet again. For instance, the request that ran through social media associated with Qanon was to stop “wasting” resources on the current COVID-19 pandemic and instead focus our attention and on vulnerable children. This represents a highly problematic call to action. We know that protecting vulnerable children and addressing a pandemic are not mutually exclusive. In fact, many advocates I talk to worry that ignoring the pandemic will make things more dangerous for vulnerable adults and children since the longer it continues the more isolated people may become from support systems and resources.

Consider also, what harms might occur if these current fears and ensuing interventions are used to target people not because they perpetuate a crime but because they are outsiders. Along with calls to ignore COVID in favor of saving children, another related exhortation has been re-circulating social media warning us that now that we have “allowed” people to marry the same gender or identify as gender-fluid there is a wave of pedophiles trying to justify sex with minors by identifying as “age-fluid.” Not only is there little evidence that this is common or actually exists at all, but it is eerily similar to past moral claims which labeled vulnerable outsiders as the heart of the problem while encouraging us to ignore the real circumstances that exacerbate it. The idea of adults sexually exploiting children sounds morally reprehensible. But we are being asked to blame LGBTQ+ people for creating and enabling the social problem. In reality both commercial and non-commercial sexual exploitation are likely to be perpetuated by people in power who know the children they exploit. Most evidence suggests that the LGBTQ+ people we are being pushed to scape-goat are much more vulnerable to being sexually exploited themselves compared to the average population.

The world of anti-trafficking efforts in the U.S. is already highly diverse and complex. Advocates and survivors do not always agree on how to define things like exploitation, recovery, and appropriate interventions. However, they all seem to feel the threat represented by the misconceptions that can accompany moral panics. They feel a constant struggle both within and outside their community to educate others and dispel misconceptions associated with the social problem they seek to address. Given this reality, sudden bursts of moral-panic-like public attention can be challenging. On the one hand they want and need people to be aware of human trafficking as a problem in order to gain financial and political support for their cause. On the other hand, if that awareness is driven by fear rather than compassionate and victim-centered understanding of the problem the attention may create more problems than it solves.

This Too Shall Pass . . . Kind of.

Like other moral panics of the past, Qanon’s particular narrative is likely to fizzle. Over time, lack of evidence and a shifting political landscape will direct attention elsewhere. However, if it follows the cycle of other moral panics it will not go before it causes us to “intervene” in human trafficking in potentially harmful ways.

Even if nothing tangible comes of the current Qanon crisis, our social propensity to panic over alleged harms of sexual exploitation will remain and another “Qanon,” with its ensuing social consequences, seems inevitable. Public demands that the government “do something” about sexual exploitation and vulnerability shape the landscape of our culture and institutions. Since the first modern spike in attention toward human trafficking at the turn of the century spurred the passage of the Mann Act, federal and local governments, nonprofits, and faith groups around the nation have spent millions of dollars forming human trafficking task forces and intervention programs. As every fresh wave of public concern focuses fear and moral outrage on potentially- imagined or exaggerated problems we must ask: what will all that economic and moral capital be used for?

The social fault lines that create these storms run deep. We are unlikely to eradicate fears associated with racial, economic, sexual and political differences any time soon. For the beleaguered advocates, victims and survivors who have to navigate them, public attention around these controversies will continue to act as a double-edged sword: forcing some to confront the harms of exploitation and enabling others to capitalize on the ensuing fear as they push social and political agendas

Suggested Readings

Stanley Cohen laid out the first theory of moral panics. He described a five-stage process in which a certain group of outsiders gets labeled as the source of a potential moral problem. In his theory after the moral “problem” is identified there is widespread media attention to the issue followed by public concern, official response and finally social change.

- Cohen Stanley. 1972. Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and the Rockers Routledge NY

Later sociologists expanded on this concept to ask: who or what social groups start a moral panic and why do they occur at certain times but not others? Goode and Ben Yehuda argue that moral panics happen when multiple levels of society engage in and become focussed on an event, or persons that stoke “latent” social fears.

- Goode, Erich, and Nachman Ben-Yehuda. 1994. “Moral Panics: Culture, Politics, and Social Construction.’ Annual Review of Sociology 20(1): 149-171.

- Goode, Erich, and Nachman Ben-Yehuda. Moral Panics: The Social Construction of Deviance. 2nd Ed. 2009. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Elements of moral panic theory are often used to explain public interaction with matters that have to do with sex and gender. Weitzer argues that the idea of human trafficking itself should be understood as a socially-constructed problem.

- Weitzer R. The Social Construction of Sex Trafficking: Ideology and Institutionalization of a Moral Crusade. Politics & Society. 2007;35(3):447-475. doi:10.1177/0032329207304319

Many scholars continue to find elements of moral panic theory helpful especially in studying criminology and media although there are debates about how best to refine and apply the theory.

- Critcher, Chas. 2008. “Moral Panic Analysis: Past, Present, and Future.” Sociology Compass 21: 1127-1144. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00122.x

- Garland, D. 2008. “On the Concept of Moral Panic. Crime, Media, Culture 4(1): 9-30.