During the Great Depression of the late 1920s, suicide rates in the United States reached an all-time high, topping 22 suicides per 100,000 persons. Images of once-wealthy business moguls and industrialists throwing themselves from Manhattan skyscrapers may seem a tragic memory of years past, yet contemporary data show that suicide rates ebb and flow dramatically with ups and downs in the economy—especially for men.

Suicide, or taking one’s own life, was the 10th most common cause of death in the United States in 2009, with rates consistently higher for men than women, and whites relative to blacks. Young adults (ages 20–24) have higher suicide rates than children, teenagers, or other adults, yet white men ages 85 and older have the highest suicide rate of any demographic group. In recent years, highly publicized suicides among military veterans and gay and lesbian adolescents has called attention to the special stressors facing these subgroups. At an individual level, suicide is influenced by a range of social, psychological, and biological factors, most notably untreated depression. At a population level, however, aggregate level suicide patterns mirror macroeconomic trends, including unemployment rates and business cycles.

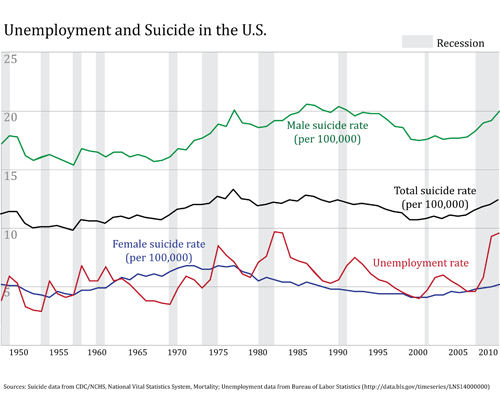

The graphic above shows U.S. unemployment rates and suicide rates among men and women from 1948 to 2011. For men, suicide rates follow patterns that roughly mirror national unemployment rates. Unemployment spiked in the 1970s—a period marked by an oil crisis and stagflation—and again in the “double dip” recession years of the early ‘80s. Men’s suicide rates also spiked during these periods, and remained quite high throughout the ‘80s, before dipping during the dotcom boom years in the ‘90s. During the recession beginning in 2007 and continuing today, unemployment rates have again spiked, and men’s suicide rates have followed a similar, although more muted, pattern.

Women’s overall suicide rates are consistently lower than men’s, averaging close to 5 per 100,000 (versus roughly 18 per 100,000 among men). Women’s rates were highest during a strong economic period: the late 1960s through 1970s. By contrast, during the recessionary periods of the early 1980s and early 21st century, women’s suicide rates were low and stable.

It is impossible to “prove” whether aggregate level patterns of economic distress trigger men’s suicide or whether individual women’s suicides are a response to widespread social and normative unrest like that at play in the late 1960s. However, sociological writings dating back to Emile Durkheim suggest that any social phenomenon that weakens a person’s sense of social integration and connectedness or that profoundly undermines feelings of self-worth may trigger depressive symptoms, a common underlying cause of suicide. Stress theories also find that major stressful events, including job loss or home foreclosure, may create a string of “secondary stressors” including marital troubles, residential relocations, and disruptions to one’s daily activities and routines. All of these secondary stressors may place one at risk of depression, anxiety, and substance use—all potential triggers of suicidal behaviors. These risks may be particularly acute for men, who are socialized to believe that a man’s worth depends on his ability to be his family’s “breadwinner.” Although publicly funded health initiatives also suffer during lean economic times, suicide prevention and depression treatment programs are all the more critical during times of recession.

Comments