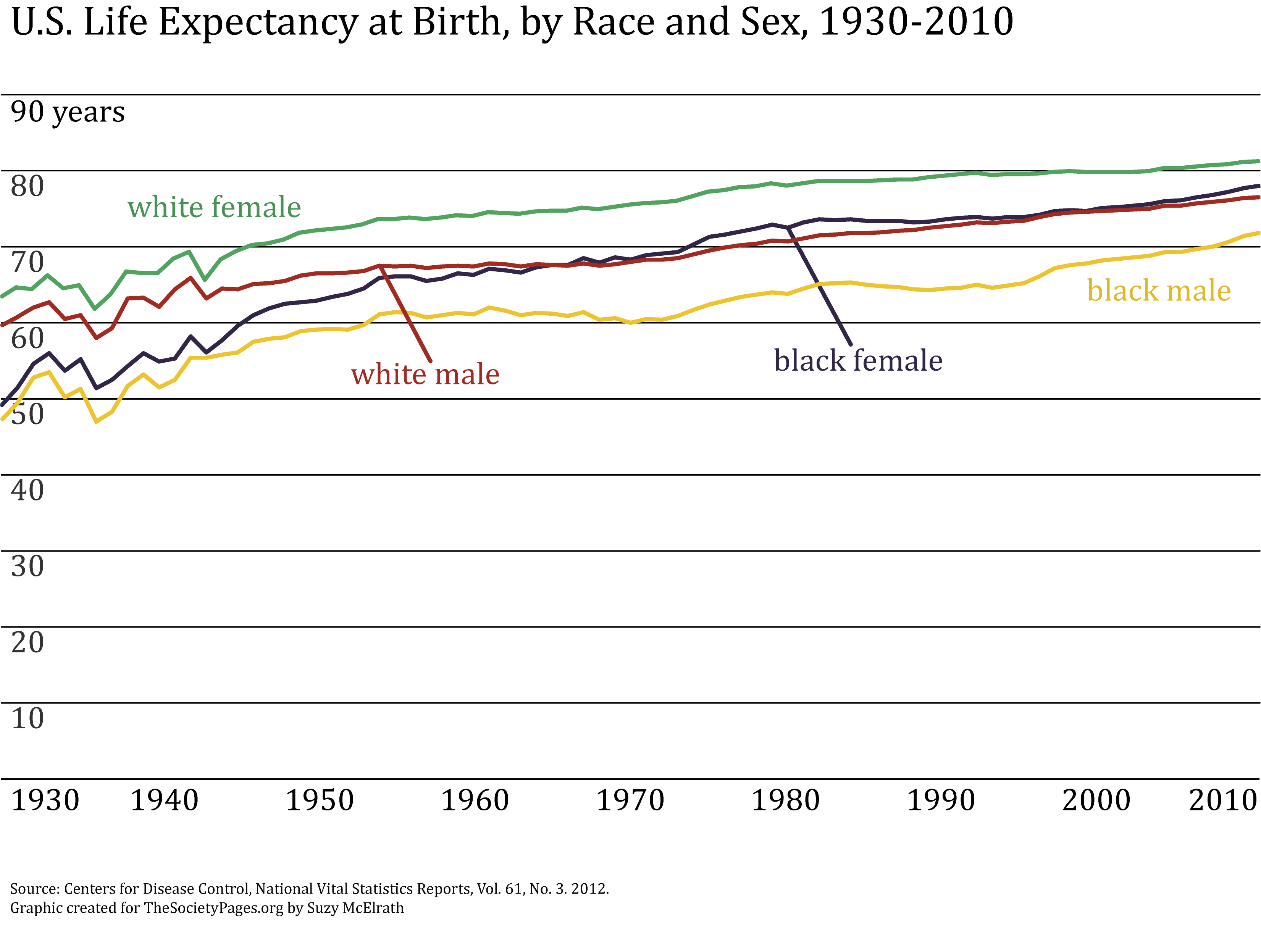

Death has been poetically referred to as the “great equalizer,” yet epidemiologic data tell a different story. The age at which one dies varies dramatically by race and gender, with women maintaining a clear advantage over men, and whites and Hispanics enjoying longer life spans than their black counterparts. One of the most persistent disparities in life expectancy at birth, the black-white gap, has narrowed over the past century—reaching an all-time low in 2010. Throughout the 20th century, life expectancies have increased for all subgroups in the United States, as shown in the first figure below.

Increases in the early 20th century are due mainly to improvements in sanitation, nutrition, effective public health initiatives, and the development of vaccines for some infectious diseases. Since the mid 20th century, life expectancy increases mostly reflect advances in medical technologies that have lowered death rates due to heart disease, cancer, stroke, and chronic lower respiratory diseases. In the last two decades, gains have been steepest for black men, due largely to improved treatment of heart disease and AIDS among this group.

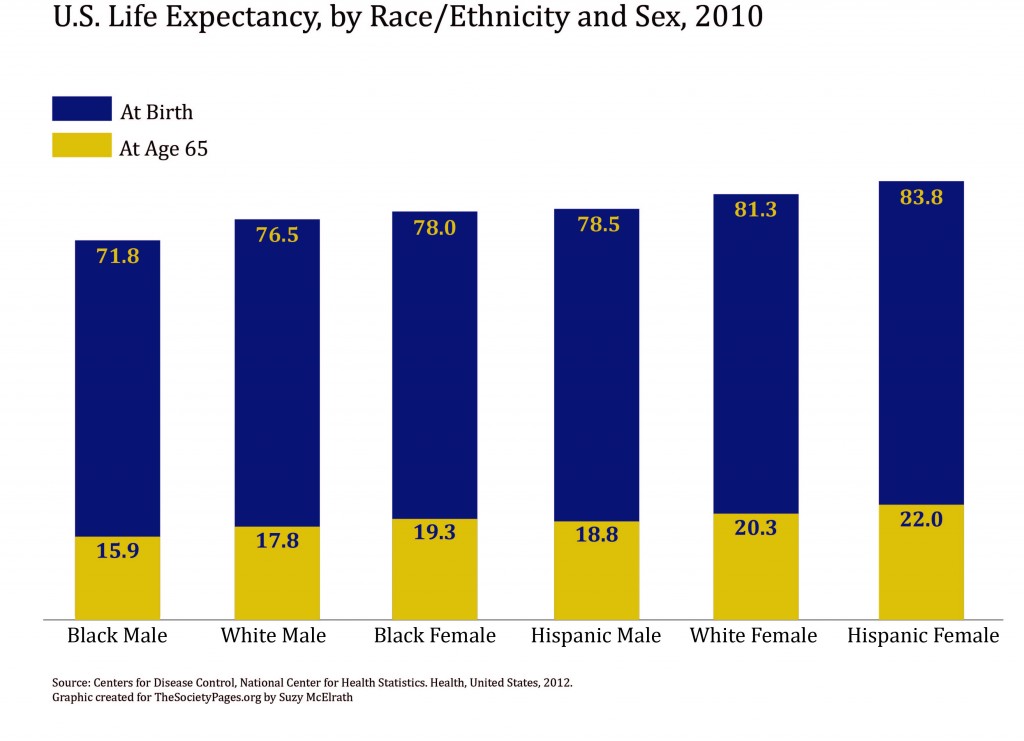

Despite the gradual (though incomplete) convergence shown above, stark race gaps in life expectancy at birth persist today. The figure below reveals that a non-Hispanic black baby boy born in 2010 can expect to live just 71.4 years, compared to 76.4 and 78.5 years for non-Hispanic white and Hispanic men, respectively. Although women live considerably longer than men, a black baby girl born in 2010 is expected to live 3.5 fewer years than her white counterpart, and roughly 6 years less than her Hispanic counterpart (77.7 versus 81.1 and 83.8 years, respectively).

What accounts for these persistent (albeit declining) disparities? Part of the answer lies in how life expectancy at birth is calculated. This snapshot of a population’s longevity refers to the average number of years a new baby can expect to live. As such, it is highly sensitive to premature death; estimates can be depressed considerably by deaths in infancy, childhood, or young adulthood. For blacks, and black men in particular, premature death is all too common. Infant mortality rates are roughly twice as high among blacks as whites, and homicide rates are roughly five times higher, with an even more pronounced gap among men ages 15–24. These disparities in early mortality risk contribute to the disparities in life expectancy at birth.

Persistent inequalities over the life course also account for the black disadvantage. Blacks are less likely than whites to have health insurance, regular medical care, and early screening for health problems. They also have less access to nutritious food in their communities and are less likely than other ethno-racial groups to live in exercise-friendly, safe neighborhoods. Blacks are more likely to experience neighborhood poverty, racism, poor quality employment, and other stressors that may increase their risk of illness and death.

Latinos face many of these structural obstacles as well, yet some experts have argued that their health advantage reflects two main factors: selective migration and high levels of health-buffering social support. First, those Latinos who moved to the United States may be particularly healthy and robust, to have withstood and survived the rigors of the migration process (the “healthy migrant” thesis). Others argue that high levels of social support, especially for pregnant women, infants, and older adults, contribute to the overall Latino longevity advantage.Through the process of “selective survival,” the steep life expectancy gaps evidenced earlier in life fade.Interestingly, blacks’ relative disadvantage in longevity diminishes in old age. If black men and women withstand the challenges of neonatal, childhood, and young adulthood health threats and survive until age 65, their future time horizons start to approximate their white and Hispanic counterparts. At age 65, a black man can expect to live another 16 years, compared to 18- and 19-year horizons for white and Hispanic men, respectively. Similarly, a 65-year-old black woman can expect to live to about age 85, whereas her white and Hispanic peers can expect to live just one or two years beyond that. Through the process of “selective survival,” the steep life expectancy gaps evidenced earlier in life fade.

From a policy perspective, the most effective way to ensure that blacks, whites, and Latinos survive until their later years is to eliminate economic disparities that impede access to timely high-quality care and encourage social environments that foster healthy living.

Comments 7

Corey Remle — September 11, 2013

It is unfortunate that the stark differences in life expectancy by race & gender you are discussing are not matched well with the figures from the CDC. The figures are misleading. For the first one, the y-axis marks are not wide enough to appear significant even though we know they are. 5-year measures would be clearer than 10-year measures. The second figure is misleading in life expectancy for those who have already reached age 65. I understand the intention but only because I'm familiar with the points being made in the article. By comparison, I looked your earlier post about homicide rates that is hyper-linked above. The disparity in homicide rates is much clearer on the figures in that post. I think the CDC figures would benefit from an analysis on the Sociological Images blog for TSP.

Kristjan Birnir — January 23, 2014

What load of ballox this article is. It doesn't matter what your social status, sex or race is or "who you are", you are not immune to death. All this article does is pointing out that if you belong to certain social group, sex and race, you might live longer, but that doesn't make you immune form death. No matter what. So yes death is the great equalizer, even if this article is trying to make you belive other wise.

Friday Roundup: Sept. 13, 2013 » The Editors' Desk — April 1, 2014

[…] “Social Fact: Death—Not the Great Equalizer?” by Deborah Carr and Julie A. Phillips. Race and gender affect life expectancy, but it’s surviving the first quarter of life that really seems to make the difference. It’s also important here to check out the previous Social Fact, on race and homicide rates. I’m not sure I’ll ever get “not horrified” with the fact that murder is the most common cause of death among any race or age group. […]

nevvie — March 25, 2015

Agree with Kristjan Birnir, this article is rubbish. It's actually stating how life is unequal, and how some can live longer than others. But when you're dead that is it, you're as dead as dead can be, whether you're rich or poor, black or white, good or bad!

ying — February 26, 2016

People are looking for "Equality" as always, that's normal and being part of our human nature. While I think animals don't seek "Equality". Only we, human beings have this deep desire to seek the "Equality" that exists only in an Ideal World or a.k.a. Heaven. That means we came from some "perfect" world before we were born to this world. Or else, why would we often look for "Equality" in every aspect of life, even death? We forget that we are still living in this imperfect world. We are here for some spiritual purposes or soul growth. ?

Bobby Fisher — January 4, 2017

It is called "the great equalizer" bs we all die. I'm glad humans don't live to be 200-300 years-although some act as if will. It would also suck to die & right after, they find away to not get old & be mortal.

K man — March 27, 2017

By death being the great equalizer, what most people would perceive is that regardless of a persons socio-economic background, our return is in the same humble origins. We came from dust, and there is our final return. Both the king, and the beggar will return to the same humble state thus being equal.