Student Debt, For-Profit Education, and the Federal Government

According to the Department of Education (ED), for-profit universities educate about 12% of college students yet these students are responsible for about half of student-loan defaults. Increasingly, these institutions are under legal attack from former students, state regulators, and even the Department of Justice. The obvious solution is to sanction or shut down the most flagrant debt-for-diploma mills, but the reticence to take such steps brings to light another, more disturbing issue: the federal government would have to forgive federal loan debt from schools that shut down or lose accreditation.

In today’s lexicon, “too big to fail” usually refers to companies that are large in size or market share, but that’s not what’s key. A firm actually becomes “too big to fail” when it achieves a level of importance that discourages regulators from stopping its bad behavior. For-profit universities are now some of the nation’s largest educational institutions (in terms of enrollment numbers and student loan obligations), but some may also be too big to fail. Students at some of the largest for-profit universities now have so much outstanding loan debt that shutting down the institutions might be more painful to federal regulating bodies than simply allowing the universities to continue. Because of their prolific growth and massive size, the ED now has a financial disincentive to shut down or remove accreditation from these schools. That is, fear of a massive potential write-down is protecting some of the largest for-profit universities’ access to federal student loans.

For-Profit Boom (and the Coming Bust)

The American education market is changing. Critics attack the commercialization of education, with its focus on earning potential after graduation (“return on investment”) over the pursuit of knowledge before graduation. But the commercialization starts earlier—at the recruitment stage. The business is more about increasing enrollment numbers and tuition dollars than personalized education decisions, meaning the worst offenders are for-profit institutions that promise democratized educations to all. No longer limited to trade schools and providers of part-time graduate degrees, for-profit institutions bombard potential students with print and media advertising and direct them to online and accelerated educational programs. This unconventional educational format is in many ways a race to the bottom, with institutions competing for the shortest degree completion times, most lenient instructors, and most flexible schedules. Despite this, for-profits offering these amenities are likely here to stay, and their presence has created a stratified educational system. Prospective students can choose from exclusive, expensive, and demanding full-time programs or for-profit systems that promise fast, real-world education and part-time study. As traditional universities attempt to become more prestigious and for-profit schools fight to offer the easiest path to a degree, the educational journeys they offer grow ever further apart.

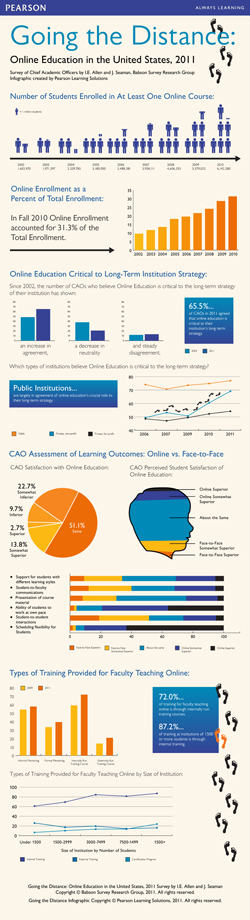

Five of the ten schools with the highest amounts of total outstanding student loan debt are for-profit universities with electronic distance-learning programs. Educating students online allows universities to offer degree programs that are not limited by geography or time of day, and oftentimes do not require additional faculty hires. These programs are now much larger than traditional colleges, and their total loan amounts will continue to grow faster.

The real worry about online for-profit education isn’t actually a lack of quality instruction, but the simultaneous lack of marketable degrees and the reality of student loan debt. Many for-profit schools began in the second half of the twentieth century as niche schools—niches, though, are not typically sustainable high-growth areas, and for-profit schools now run national campaigns directing prospective students to online portals and marketing themselves as replacements for traditional college and community college educations. They concentrate on reaching student populations such as first-generation college students, older students, and college dropouts, promising experiential programs and easily obtained degrees. In doing so, they became more expensive, less specialized, and more aggressive in recruitment. As their investors demand growth, these institutions attempt to convince more and more students that the value of a college education is enormous and any amount of debt is worth the panache of a college diploma. These sales tactics, coupled with exploding tuition amounts and vulnerable student populations, have created universities financed almost exclusively by government loans.Is the Phoenix a Canary?

The growth of education loans is actually representative of changing attitudes about debt in the United States. From 1999 to 2009 period, college tuitions grew about 32% (accounting for inflation). This change did not occur in a vacuum. Buoyed by access to more credit cards, home equity loans, and college loans, and a cultural attitude about “good” debt, demand for college education rose alongside prices. Benefitting from this era of broadband Internet, increased debt tolerance, and a strong demand for education, for-profit universities experienced a banner decade that is not likely to be repeated.

But unconventional schools often seem to end in disaster: new competitors come to market, tastes change. So far, only small for-profit schools have shut down or lost accreditation; the subsequent loan forgiveness amounts have gone unnoticed, absorbed by the greater economy. Further, forgiving loans seems like a good idea, the right thing to do: students enter a program under the assumption that they will be able to obtain a degree, and if they are unable to complete their education because the school collapses, it seems only fair that loans taken out to obtain a product that no longer exists should be forgiven. Those students who do complete their degrees only to see their alma mater collapse are left with an education deemed worthless or lacking credibility; they suffer in the job market, so we can easily justify forgiving their loans. All of this is to say, in the past, trade schools and small for-profit universities failed without really drawing attention. Now that’s nearly impossible. For-profit online universities are the whales of the student loan debt market. The University of Phoenix holds the honor of the highest amount of total student debt at a single institution. With student loan debt in the billions, the largest for-profit universities may very well be too big to fail.

Paradoxically, these institutions are also far too big to succeed. Education is clearly not a priority: the aforementioned giant, University of Phoenix, has a six-year bachelor’s degree graduation rate of only 9% according to the Education Trust, far below traditional universities and its for-profit peers. Graduation rates at some for-profit programs are so dismal that many states’ attorneys general and the Department of Justice are examining their practices.

In many ways, the University of Phoenix is the canary in the coal mine. While the institution is extremely large, the important numbers are all about growth rates. Before the school experienced massive growth, the ED attempted to improve behavior at the University of Phoenix with lawsuits in 2003, audits in 2004, and program reviews afterward. By 2010, though, the ED had seemingly stopped overseeing the University of Phoenix; investors and the public were no longer aware of ED actions against the University. This is likely the result of an awkward stalemate: if the government shuts down the University of Phoenix, the ED may be on the hook for billions of dollars in loan forgiveness. Doing anything to undermine the credibility of these universities might lead to a loss of accreditation or their closure, and then all of the loans to all of the students would have to be forgiven at the federal level. The massive potential write-down can’t be ignored in considering the ED’s passivity toward delinquent for-profit universities, but it’s not a prudent long-term strategy. Each year these universities remain open, loan amounts compound, and make no mistake: these universities cannot sustain growth rates that will satisfy corporate investors forever. Having saturated the market, growth rates at the largest for-profit universities are slowing and share prices are falling. Some of these institutions will collapse on their own.

Several for-profit universities, including the University of Phoenix, are already flirting with disaster. The government mandates that no more than 90% of an institution’s loan dollars can come from federal loans. Instead of lowering tuition or providing other methods of payment, some for-profits chose to raise tuition beyond federal reimbursement levels, forcing students to pay by other means. University of Phoenix also has a history of returning all federal loans for some students who drop—it’s an attempt to keep default numbers acceptable. The University then privately sues students for back tuition.With student loan debt in the billions, the largest for-profit universities may very well be too big to fail. But they are also far too big to succeed.Despite inquiries into for-profit universities at Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee hearings, Congress created loopholes in 2008 to allow these universities to count some federal money (such as GI-Bill payments) against their 90% federal borrowing cap. That is, every returning veteran enrolled by a for-profit university allows that school to recruit nine other students paying the entirety of their tuition with federal loans. Generally, the government appears complicit in allowing for-profit universities to function for as long as possible with as many federally-backed loans as necessary.

The ED is likely reluctant to confront this issue for the same reason that banks, mortgage lenders, and the Federal Reserve were seemingly oblivious to their financial ills: the embarrassment of admitting we are in an unsustainable situation is apparently greater than the savings from calling the bluff now. Every year we wait to admit there is a crisis in the student loan industry, things will get worse. Much like the causes of the great recession, there is no shortage of guilt—there is no one fall guy, and everyone will hurt when the charade ends.

What’s a Government to Do?

If the government denies federal loans to for-profit universities like the University of Phoenix, they will instantly be exposed for their unsustainable business models and shut their doors. The government will be left holding the tab. If the ED encourages accreditation organizations to deny renewals to for-profit universities, those schools will ultimately fail. The same is true for limiting the number of new students that can enroll in these universities; if for-profit institutions stop getting new tuition dollars or downsize too rapidly, they will fail. Because of loan forgiveness laws already in place, it is impossible for the federal government to take a strong negative stance on for-profit education without losing a significant amount of money in almost immediately.

So, while some individuals and states have “seen the light” and there are numerous calls for an end to for-profit education, the federal government has a short-term financial incentive to keep the degrees granted by these educations valid. These institutions continue functioning even though regulators know they are a bad deal for students and taxpayers. For instance, even though former students of for-profit universities are defaulting on loans in unprecedented numbers, right now their debt isn’t forgiven: the onus is on the borrower, since personal bankruptcy will not eliminate many federal student loan obligations. The government, then, is publicly claiming that bankrupt students will repay their debts, but is privately aware repayment is unlikely and the expense will eventually fall to the feds. Anecdotal examples of graduates failing to launch in the face of staggering debt amounts now appear frequently in popular news outlets, and the idea of just abandoning loan payments in the vein of strategic mortgage default is gaining traction.

Short-term write-downs, though, are no excuse for silence hundreds of thousands of students are aggressively sold, persuaded, or downright duped into career-long debt and taxpayers are left liable for these loans after almost inevitable defaults. Enrollment at for-profit schools is dropping and loan defaults are rising, but the real costs to the government and taxpayers will not be realized until the schools shut their doors or lose accreditation. Based on the potential legal action led by classes of students, investors, and states, it seems it’s only a matter of time before the ED’s hand is forced. The reality is that both the for-profit education and the student loan systems are fundamentally broken, and the sooner we fix them, the better. Fixing this system will going to be expensive, disruptive, and deeply unpopular with many. We are all going to end up paying for this slow, but huge, mistake. But when the largest for-profit educational institutions are too big to fail and too big to succeed, something has to be done.Recommended Reading

Eric Best. Forthcoming, 2012. “Debt and the American Dream,” Society. Discusses the ways in which the mortgage debt crisis may serve as a template for a coming student loan debt crisis.

Rachel E. Dwyer, Laura McCloud, and Randy Hodson. Forthcoming, 2012. “Debt and Graduation from American Universities,” Social Forces. Considers student debt as both a “useful resource for making needed investments” and a harness that may increase vulnerabilities and limit options.

Anya Kamanetz. 2006. Generation Debt. The subtitle says it all: How Our Future Was Sold Out for Student Loans, Bad Jobs, No Benefits, and Tax Cuts for Rich Geezers—And How to Fight Back. See also Kamanetz’s latest book, DIY U, on an educational Reformation.

Janet Lorin. June 4, 2012. “Students Pay SLM 9.25% on Exploitative Loans for College,” Bloomberg News. A detailed reading of pay-day loan style tactics in student lending.

Andrew Martin and Andrew W. Lehren. May 12, 2012. “A Generation Hobbled by the Soaring Cost of College,” New York Times. A great overview of student loan debt and the individuals facing it.

Stanford University’s Center for Education Policy Analysis. This website is a constantly updated treasure trove of informative publications and accessible research on the conundrum of contemporary education.

Comments 3

PMCE — June 29, 2012

Whatever Govt. do, university will fill a way of loot. Even Laws are to be broke. We should have some serious and effective law against this.And These law should be abandonment frequently as universities can not thing beyond the law.

Letta Page — June 30, 2012

Hmm, though I can't engage the comment above (I'm not sure I follow, PMCE), I suspect the idea is that we need laws to regulate education loans and that those laws will need to be flexible enough to deal with those schools that work to find loopholes.

Anyway, Eric, I particularly appreciate your point about student loan debt being trumpeted (even by personal finance gurus of all stripes, by the way) as "good debt." That is, I think, often very true, provided you have a nice, low, fixed rate on a federal loan toward a degree (or a foundational education---the liberal arts are nothing to scoff at in providing a wonderful base for how to view and interact with the world as a curious and informed citizen) that will help you toward a career that's in demand (for you and for the public).

But if you've gotten a somewhat "B-rated" MBA from an online university that will help your current job give you a promotion but may be otherwise useless? That's scary stuff. (Of course, I'm old enough to not know whether that stigma lingers in the way that we were once freaked out to hear that a friend met their date online...) Meanwhile there are millions with substantial loans (sometimes private, variable rate loans) for educations that did help secure raises or promotions, but may very well also take decades to pay off. I'd be interested to see if there's any recent research on whether, these days, in this particular job market (or job markets by subsection) a degree really *is* worth its cost anymore---there've always been numbers tossed out about the lifetime value of at least a B.A. or B.S., but I wonder if the scales are tipping and if the "un-outsource-able" jobs have become more and more centered in skilled labor that can be learned more readily and less expensively in trade schools and on-the-job certification.

*All this said by someone with several liberal arts degrees and virtually no marketable talents beyond a way with words.

Amanda — November 16, 2012

I have been a victim of university of pheonix taking my money, and running. I have an associates degree that I owe $21,000 for. I have not had one employer accept my education as worth anything, All the employers look at it as nothing better than highschool, but I am stuck swimming in the debt. Its not a school of excellence, its a school that needs to be shut down, had I known going into it my degree from there school would mean nothing I never would have done it, wasted 2 years and so much money I cant afford. The suckered me into believing they were a school of honor and integrity, and no company feels they deserve accrediation. I hope the government will get on the ball, and fix our school systems, so that the disloyalty and massive mistake of keeping them open this long will shut the doors so we save other students like me to getting a real degree from a college that will mean something to anyone. This school needs to be shut down immediately, they are taking on more students money and loans and hurting so many students just trying to get an education in the process. I wish and pray I could give them my degree back for my loans in a trade. I would never do it twice with them, they profit so much and double/triple the price of what a school down the street from me would cost. Its such a scandal.