The Newest of the New CEOS

For most of the second half of the 20th century, virtually every CEO of every Fortune 500 company was a white man. In the 1980s and early ‘90s, a few white women, a few Latinos, and a few traditionally defined Asian Americans (those with Japanese, Chinese, and Korean backgrounds) emerged as Fortune-level CEOs. Then, in a three-year period between 1999 and 2002, six African Americans were named CEOs at these top-tier companies. By 2011, when we published a book about these “new CEOs”—by which we meant white women, African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and South Asians (from India and nearby countries that were once part of the British Empire)—we had identified 74 “new” CEOs, most of whom were no longer serving as Fortune CEOs, having retired, been fired, or died. The appointment of Mary Barra, a white woman, as CEO of General Motors in January 2014 and Indian-born Satya Nadella as CEO of Microsoft in February 2014 brought the cumulative total of new CEOs to 110, with 52 currently in the corner office.

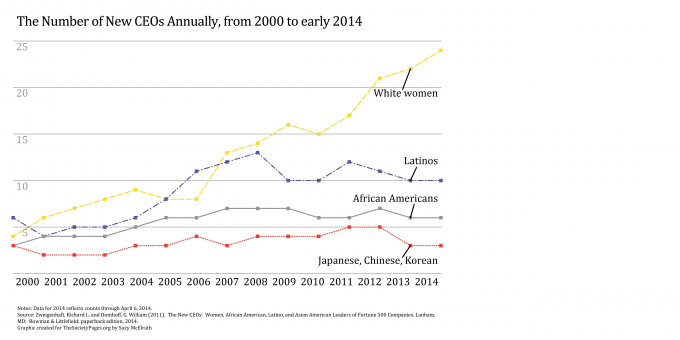

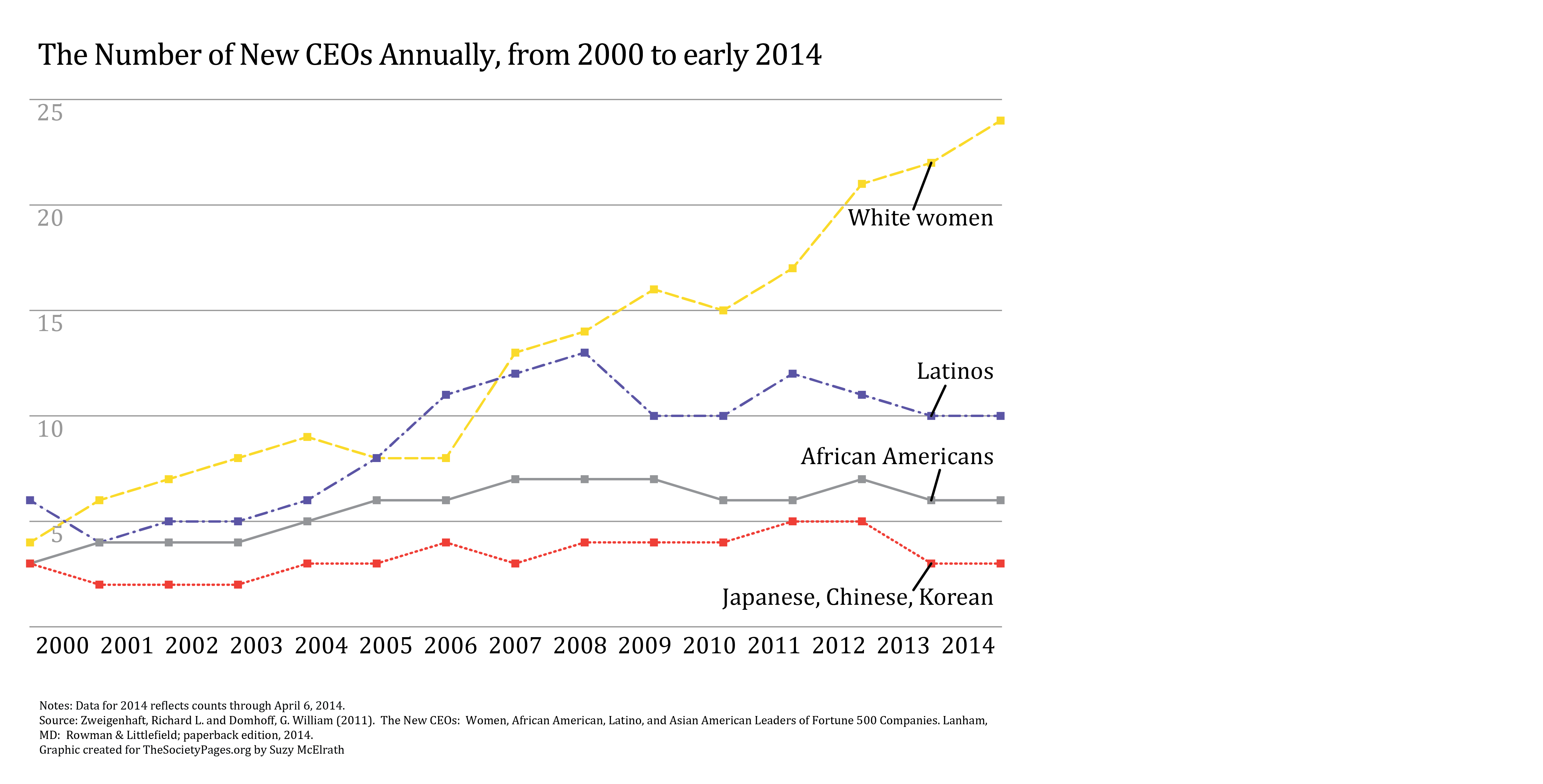

Sounds like the doors keep opening, right? Well, not exactly. Over the last few years, some new and unexpected patterns have emerged. They can be seen more clearly by looking carefully at the annual, rather than the cumulative, figures. The peak year for CEOs in office varies by racial group: 2007 for African Americans, 2008 for Latinos, 2011 for Asian Americans, and 2012 for South Asians. In contrast, the number of white women serving as CEOs of Fortune 500 companies is currently at its peak, having increased in 11 of the past 14 years. These differing patterns can be seen below.

Why have CEOs of color declined? Many factors may be at play, but we think three are especially important. First, the diversity pipeline is generally slim, and even slimmer for people of color than for white women. When we examined the gender and ethnic make-up of those on management teams (one step from the CEO office) at more than half of the Fortune 500 corporations, we found about 19% were white women, about 8% were Asian Americans and South Asians combined, about 4% were Latinos, and less than 3% were African Americans. Our analysis of national income data by gender and ethnicity for Americans who earned more than $250,000 per year led us to the same conclusion: there are still far more white men in the running for CEO than white women—and there are far more white women than African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, or South Asians.

Second, there is evidence that “restructurings” work against previously underrepresented groups. A 2010 dissertation analysis by Harvard sociologist Soohan Kim, now a professor at Korea University, based on 1,085 cases between 1980 and 2002, showed that mergers, the closure of corporate subsidiaries that had numerous women and people of color on their management teams, and emergence from bankruptcy all led to reductions in corporate diversity

Third, while the number of white women CEOs has continued to increase, there was an ominous decline in the number of women on Wall Street due to the lay-offs and terminations after the collapse of the housing bubble and the resulting financial implosion. Journalist Susan Antilla reported in a New York Times piece, “After the Boom-Boom Room, Fresh Tactics to Fight Bias,” that after 2007, there was an 11% decline in the number of women working in the financial and insurance sectors. Men saw just a 1.6% decline.

The Emergence of South Asian CEOs

The appointment of Satya Nadella at Microsoft reflects another trend when it comes to diversity: the increase in people of South Asian descent in top offices. In our 1998 book, Diversity in the Power Elite, we looked at people of Asian descent on the Boards of Directors of Fortune 500 companies, but we included only “traditional” Asian Americans (the majority were Chinese Americans, then those of Japanese and Korean backgrounds). When we wrote the second edition in 2006, we included Indians among those we called Asian Americans. By that time, 46% of the Fortune 500 directors were Chinese Americans, 21% were Japanese Americans, 16% were from India, 7% were Korean Americans, and 9% were from a cluster of countries that included the Philippines, Singapore, and Vietnam.

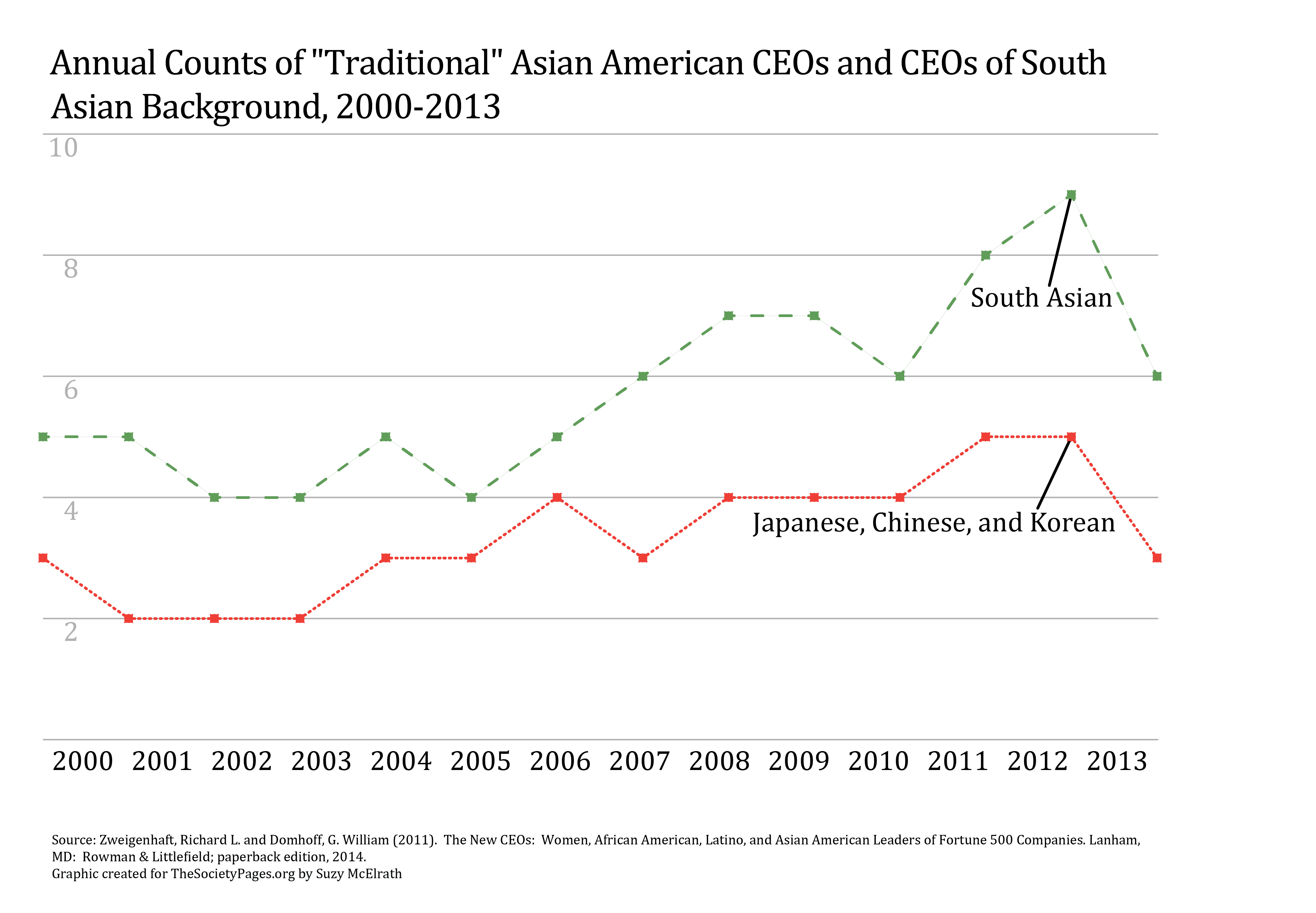

Just a few years later, when we wrote The New CEOs, we were surprised to discover that 8 of the 20 new CEOs of Asian descent had been born in India. Another three had been born in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. But only five Chinese Americans, three Japanese Americans, and one Korean American had ever served as CEOs, and right now there are only three traditionally defined Asian Americans in the big corner office. That is, in contrast to our previous data on Fortune 500 corporate directors, there are now more Indian Americans than all other Asian groups. Now, with another three years of CEO appointments and a vantage point that allows us to look back over the past few decades more carefully, we see another pattern of importance: overall there have been more South Asian CEOs than Asian Americans.

As seen in the figure above, when we graph the year-by-year numbers for both groups from 2000 through the present, the number of CEOs from South Asia almost doubles while the number of those with Chinese, Japanese, or Korean backgrounds increases from three to five. Notably, from 2012 to 2013 there was sharp drop-off for both sub-groups.

We have studied the class backgrounds of the South Asian CEOs, and, as has been the case for about two-thirds of the CEOs of America’s largest corporations for the last hundred years (despite their claims to the contrary), most come from economic privilege. In other words, the South Asian CEOs, by and large, came from the colonial elites of the former British Empire, and, because most were born into families of economic privilege, they typically arrived in the United States with a good British-style education (sometimes from elite schools) and a sophisticated command of the King’s English.

There is one new CEO who does not fit any of the categories, although he does fit our findings on class and educational credentials. In 2008, Coca-Cola appointed Muhtar Kent. Born in New York City, Kent is the son of a Turkish ambassador (his father also served in Thailand, India, Sweden, and Poland). He left New York City as a toddler, went to high school in Turkey, and then did undergraduate and graduate work in London. He started working for Coca-Cola in 1978, and over the next 30 years moved up the management ranks in that country (with a six-year break from 1999-2005 when he served as CEO of a European beverage company).

* * *

Three things seem to be going on in terms of our “new CEOs” in these last few years. First, the number of white women CEOs has continued to increase. Second, the number of African American, Latino, Asian American, and South Asian CEOs are now in decline (though the decline for Asian Americans and South Asians is more recent). Third, there have been more CEOs from South Asia than the more traditional category of Asian Americans.

There’s one more constant: with the exception of African Americans, the large majority of the new CEOs was born into the top 15% of the class structure, is better educated than the white male CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, and tends to be light-skinned. All in all, the new CEOs, who now make up slightly less than 10% of all Fortune 500 CEOs, bring some diversity to the table—along with a great deal of cultural, educational, and social capital

Recommended Reading

Nancy DiTomaso. 2013. The American Non-dilemma: Racial Inequality without Racism. New York: Russell Sage. DiTomaso argues in this interview study of white Americans that, in the post-Civil Rights period, whites no longer have to do overtly bad things to nonwhites, or actively exclude them, to benefit from racial inequality; instead, whites helping other whites may be as much a factor in reproducing racial inequality as whites discriminating against blacks and other nonwhites.

Frank Dobbin, Soohan Kim, and Alexandra Kalev. 2011. “You Can’t Always Get What You Need: Organizational Determinants of Diversity Programs,” American Sociological Review 76:386-411. A study of the forces that promoted the use of six different kinds of diversity management programs at 816 corporations over a 23-year period.

Richard L. Zweigenhaft and G. William Domhoff. 2003. Blacks in the White Elite: Will the Progress Continue? Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. This book shows that low-income African Americans can rise to the top in just one generation, if given the chance through a prep-school scholarship that allows them to acquire the necessary social and cultural capital that is usually only available to those from privileged backgrounds.

Richard L. Zweigenhaft and G. William Domhoff. 2006. Diversity in the Power Elite: How it Happened, Why it Matters. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. This book looks at the extent to which Jews, women, African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and gay men and lesbians have made it into the power elite and the pathways they have taken to get there.

Comments