It is quite extraordinary to sit in a Lifers Club meeting at the Oregon State Penitentiary. First, the facts: individuals who identify as “lifers” have been convicted of taking a life and have made a commitment to change their own. Only about 5% of the prison’s population is among its members, and they generally face decades together in this insular society of captives. As might be expected, looking around the room, there are older men, grizzled and withered from years of confinement; hard-to-miss tattoos proclaiming past loyalties, lost loves, and diminished hope; and cynicism in the eyes of those who think their fall was harder or less just than was warranted. And then, against every prison stereotype, there are the young elected officers of the club, working the room with focus and patience. These leaders listen to others’ concerns, accept advice and suggestions, and steer the Lifers Club toward positive contributions to the “inside” and “outside” community.

The men in the room (including two of this article’s authors) have made a choice to be active members of the Lifers Club; in doing so, they recognize the harsh reality that the terrible acts of their pasts can never be erased or undone. They hope to use the long years in prison to come to terms with their histories and prepare for very different futures. The ledgers may never balance, but the club’s young officers share a deep belief that the Lifers owe a significant debt to society. They are focused on beginning reparations. The positive energy is palpable: if it were not for the “prison blues” (standard issue denim), the stark setting, and the uniformed officers standing in the corners, it would be easy to mistake this group of young men as graduate students, business men, or fraternity alumni. They are clean cut, active, and vital. But they live within the walls of a maximum-security prison.

Trevor, the current President of the Lifers Club, is all laser focus and determination, striving to meet his proclaimed goal to give 100% of his effort 100% of the time. At the age of 14, Trevor’s time started on a life sentence with 30 years served before the possibility of parole. Not yet 29, Trevor has now spent just over half of his life behind bars. In one way, Trevor is fortunate: because he was too young at 14 to be sentenced under the state’s mandatory minimum sentencing laws, he will soon have the opportunity to get a “second look”. His sentence and conduct will be reviewed; if he is not released at that time, he will be entitled to regular hearings with the parole board.

Trevor and the other elected Lifers Club leaders are strikingly young. Four of the five officers were teenagers at the time of the crimes that brought them to prison. The Vice-President, James, is a poet and self-taught artist. His goal is to have a family when he gets out of prison. James was 16 when he and his friends made the worst mistake of their lives; his first offense brought him a mandatory-minimum sentence of 25 years. He is midway through that sentence now, a young man in his early thirties trying to grow, mature, and find meaning while serving another full decade in prison. Trevor’s older brother, Joshua, is the Secretary of the Lifers Club; Josh was 18 at the time of the crime that brought him and his brother to prison. In his early thirties now, he too is serving a 25-year mandatory-minimum sentence. Blessed with extra doses of charisma, Josh is focused on self-improvement, balancing college classes, work, and family responsibilities from within the prison. Fred, another young leader in the Lifers Club, has a distinctive voice and humor. He has worked to overcome his troubled youth to become a positive role model for the son he left on the outside.

Most of the young officers of the Lifers Club are in prison as first time offenders (albeit for very serious crimes), and they have quite literally grown up in prison. Each was incarcerated in his teens, but will likely have the opportunity to get out of prison after serving long mandatory-minimum sentences. If and when they are released, they will be middle-aged or older, facing entirely new challenges and a vastly changed culture outside the prison walls. In the meantime, they must decide how to channel their youth and vitality behind bars. The long lists of activities and accomplishments these Lifers have chosen demonstrate that prison time does not have to be wasted time. They believe they can be instruments of positive change within the prison while also finding ways to contribute to the society outside.Scanning a club meeting, one can count several other Lifers who were 15 or 16 years old at the time of their crimes. Many were convicted while still teenagers. While official sentences of life without parole are rare, some members of the Lifers Club will face what criminologists Robert Johnson and Sandra McGunigall-Smith have called a “virtual death sentence” – a slow death by incarceration rather than execution. In some cases, judges have sentenced juveniles to longer than their life expectancy (for example, 15-year-old school shooter Kip Kinkel received a sentence of 110 years without the possibility of parole), but in most cases, the juvenile lifers must serve a minimum number of years before appearing before the parole board. The parole board then has the discretion to release or continue holding the prisoner indefinitely. Because these are often highly publicized homicide cases, it is frequently politically untenable for the parole board to opt for release.

Teenage Lifers

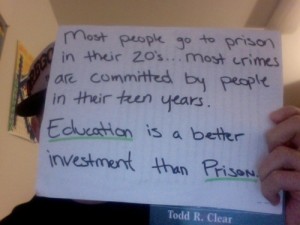

When people under the age of 18 are sentenced to long prison stints, they frequently start their confinement in juvenile or youth correctional facilities. Generally, these facilities have a smaller staff-inmate ratio and more focus on education and rehabilitation. This consideration of placement implicitly recognizes the difference between teen and adult maturity levels. Yet, under mandatory-minimum sentencing, enacted amidst widespread fear of a new generation of juvenile “superpredators” in the 1990s, teens are frequently given sentence lengths as long as their adult counterparts. More troubling, the latest neuroscientific evidence shows convincingly that adolescents’ brains are still in formation; sentences went up in the ‘90s, but the most current science says teenagers may actually be less mature and capable of making good decisions than was previously believed. As psychologist Laurence Steinberg has shown, adolescents tend to be more impulsive, more susceptible to peer influence, less oriented to the future, and less capable of weighing the costs and benefits of actions than adults.

This research on the adolescent brain may—and should—cause us to re-think our punitive treatment and sentencing of juvenile offenders. As Steinberg notes, if we recognize the difference in adolescent development and brain function, juvenile offenders should be treated more leniently than adults. In recent years, the Supreme Court has made policy separating juveniles from adult offenders in terms of the most serious sanctions, ruling that juvenile offenders can no longer be sentenced to death (Roper v. Simmons, 2005) or to life without parole (Graham v. Florida, 2010; Miller v. Alabama, 2012). The 2012 Court was deeply divided in issuing the ruling that sentencing youth to die in prison is cruel and unusual punishment, and while this decision offers some hope to the approximately 2,000 adolescents serving life without parole in the United States, many thousands more are routinely given sentences that send them to prison for decades.

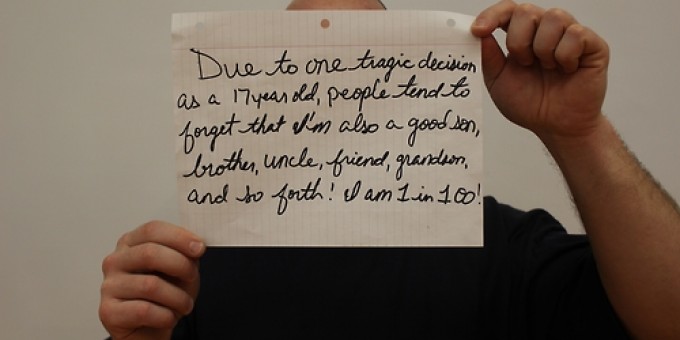

Whether it is ethical to hold teenagers fully responsible for their criminal acts when they do not enjoy the other rights and privileges of adulthood is a question for continuing and vigorous debate. In the meantime, those committed to life sentences as juveniles must survive 20-30 years in prison with their sanity intact. Some may spend years in anger and rebellion, but eventually each must decide how he wants to spend the years, whether to simply “do the time” or instead become a “gleaner,” as convict-criminologist John Irwin described those who seek productive outlets to improve their skills and minds in the prison environment. They may channel their energy into education, programs, and prison clubs, or they may become self-taught artists, learning guitar, drawing, painting, or craftsmanship working with leather or jewelry. As the young leaders of the Lifers Club demonstrate, individuals are capable of exercising efficacy and choice even in desolate circumstances.

Growing into Leadership

For many teenagers charged with serious crimes, their first transition to imprisonment occurs in county jail or detention as they await trial. As Josh explains, “I grew up a lot in county jail, because I was there for almost a full year before heading to prison. I was 18 when I got arrested, and so it was quite a shock being locked up for the first time. I looked even younger than 18, and the jailers didn’t really know what to do with me at first, so they kept me in solitary confinement for the first 2 weeks… Awaiting trial is a scary time, and I just kept thinking that I couldn’t possibly get convicted and there was no way I would be sentenced to 25 years. But then I kept watching my fellow prisoners getting convicted and sent to prison, and I had no clue about the real justice system or the way things worked.” Once he was transferred to prison, Josh remembers feeling lonely, intimidated, anxious, scared, and sad. He was afraid to let his guard down, a fear that has had long-term impact: “I was a 135lb. boy at 18. I put on 50 pounds the first year because, in prison, size equals strength…. I built up a pretty tough shell, a weird kind of filter, something I still struggle with.Perhaps surprisingly, Trevor found being one of the youngest men in prison a comfort: “Strangely enough, it has been more uncomfortable to grow ‘old’ in prison (relative as it may be)… there’s always been older prisoners looking out for my best interest and an amazing support system from my family. Having my brother [Josh] serving time with me… is very sad, [but] in other ways it certainly has its benefits. Knowing without any doubt that I have someone I can count on is of great value.” An experience when he was first incarcerated at 14 had a positive impact on Trevor: “The very first detention center I was housed at after losing my freedom had a teacher that had the words: ‘Patience, Endurance & Self-control’ written all over the classroom. These words have also been huge motivators to guide my life – a pretty positive message for the first months of my incarceration. I’ve also developed an understanding that, no matter where I live, ultimately I make the decisions that direct my future. We all have the power of choice, even if only in how we react to the actions of others.”

Aging in prison is inevitable. Growth is optional. Those entering correctional institutions and immersed in prison culture as teenagers face an especially difficult path in their attempts to mature and develop into the men they hope to become, men their families can be proud of. Josh quickly figured out that he wanted to make his time in prison as productive as possible. He pursued self-improvement whenever he had the opportunity: “I took cognitive skills classes when I felt a need to be better at dealing with my thoughts and feelings. I took jobs that would teach me a skill I wanted. I took parenting classes because I wanted to be a better parent (and a better son).” His relationships with both his brother on the inside and his family on the outside help him to “keep my focus on freedom and real world problems instead of becoming institutionalized and concerning myself only with the dramas of prison. Having a relationship with my wife and the children she brings to our marriage has helped me to grow and mature in ways I doubt I would have without her.Following his older brother’s lead, Trevor , too, has sought out opportunities to develop skills and become a responsible adult within the prison system, but he recognizes the challenges of doing so in such a restrictive setting: “I really didn’t have ‘responsibilities’ of an adult before I lost my freedom. Even today, while I do my best to acquire those kinds of responsibilities, until given the opportunity in the free world, I’ll not truly know what it is to be an adult who’s responsible for their own welfare.”

While he cannot test whether he is ready for adult responsibilities in the larger society, Trevor focused on earning his high school diploma while in a youth correctional facility and then shifted his focus to employment and job skills as a young adult in prison. He put in long hours in the prison’s industrial maintenance shop, learning and growing into a leadership role. His recent involvement in college classes and a brief stint as a clerk for the Lifers Club shifted his energy and focus, and his trajectory into program and club leadership has been swift. Trevor became treasurer of the Lifers Club and was quickly elected president, the youngest ever chosen to represent the membership. He takes the Lifers Unlimited Club’s mission statement—to “improve the quality of life for those inside and outside of these walls”—seriously and utilizes the patience and persistence he has cultivated to make positive changes in his environment.

In viewing their roles as leaders in the Lifers Club, both Trevor and Josh are quick to point out the importance of respect and mentoring. In recounting his transition into prison, Josh explains: “I just tried to conduct myself respectably and I was lucky to have the other guys around me who were patient enough to correct me if I crossed the line and talk to me about any social mistakes I made in my new society… [they] gave me the tools I needed to survive… I still receive advice and help from my peers.” Trevor learned from his older brother and prison elders, heeding advice such as: “Give your word sparingly and adhere to it like iron. Be polite and appreciative and expect the same in return.” His prison socialization undoubtedly helped propel Trevor into his leadership role with the Lifers Club: “The ‘old timers’ appreciate seeing someone so young who knows what respect is, knows how to do time, and has the values and morals that seem to be missing from many youth who cycle in and out of these prisons and institutions now days.”

Hope and Second Chances

Hope is a precious commodity in prison. Trevor says that even people in dark circumstance are capable of change: “Prisoners are still human beings. We do owe a debt to society and, regardless of whether or not we can ever pay that debt, we are most definitely able to change at any point along the way. Hope is something that everyone needs: give second chances, provide the tools for people to grow but don’t force them to grow.”

Second chances have been increasingly difficult to come by for adolescent offenders since the 1980s. Public opinion studies by criminologist Brandon Applegate and colleagues show that Americans generally support rehabilitation and a “tough love” approach for serious juvenile offenders. Unfortunately, the public’s apparent support for rehabilitative treatment has yet to significantly influence legislation; in policy circles, juvenile offenders are currently offered little love at all. As Alex Piquero and colleagues have noted, “support for a social welfare-oriented juvenile justice system is widespread, persistent, and deeply entrenched. Yet, despite this unwavering public opinion, punitive policies continue to be enacted.”

Young men who have come of age in prison can offer tremendous insight into what it means to grow up behind bars. While we have focused here on the experience of just two brothers, they represent a far larger brotherhood of those convicted of serious crimes as teenagers and sentenced to spend decades in prison. Both Trevor and Josh are troubled by inflexible mandatory-minimum sentencing and believe there should be more discretion in the justice system. It’s not necessarily an argument for lenience; instead, they see a clear need for careful consideration of individual circumstances and cases. Trevor explains:

“I don’t believe that I should have received a sentence of ‘life in prison with a minimum 30 years served before the possibility of parole’; however, I also don’t believe I should have been released at the age of 21 or 25. I think that regular consideration should be given to evaluate how a person has grown and changed, as well as consideration regarding the safety and security of the community.”

Josh advocates an alternative philosophy of punishment and justice, but ends with a more modest recommendation:

“[E]very case, situation, and person is different and should be treated accordingly. Sentencing should be about restorative justice, understanding the damage done and working to correct it, while at the same time correcting the behavior that caused it… punishment is commonly not corrective, as recidivism rates show. Prison is frequently a school on criminal behaviors, and those who are young and impressionable are even more susceptible to making those poor choices that will likely lead them to future crime, quite possibly worse than their current offense. I believe that age should be a strong mitigating factor in the sentencing process.”

These two men, who came to prison as boys, have grown into roles as young leaders of a maximum-security prison’s most stable inmate organization, the Lifers Unlimited Club. They are finding and channeling the energy to change not only their own lives, but also the actions and culture of the Club and the whole prison. They do what they can to prepare for their chance to get out and build lives in the community; as Josh put it: “[W]e serve ourselves best by using the time to better ourselves and become better people and better prepared for success in freedom.” In the intervening years, however, there are issues they care deeply about within the prison, and they will work to find compromises and resolutions. They make the best of a bad situation and find meaning in their lives, even as they hope for a day they can leave prison walls behind forever.

Recommended Reading

Brandon K. Applegate, Robin King Davis, and Francis T. Cullen. 2009. “Reconsidering Child Saving: The Extent and Correlates of Public Support for Excluding Youths from the Juvenile Court,” Crime & Delinquency. 55(1): 51-77. Results from a public opinion poll on juvenile offenders and appropriate sentencing.

John Irwin. 2009. Lifers: Seeking Redemption in Prison. New York: Routledge. Ethnography of prisoners who have served more than 20 years in prison.

Robert Johnson and Sandra McGunigall-Smith. 2008. “Life Without Parole, America’s Other Death Penalty: Notes on Life Under Sentence of Death by Incarceration,” The Prison Journal. 88(2): 328-346. Uses original interviews with prisoners to the sentence and experience of life without parole.

Alex R. Piquero, Francis T. Cullen, James D. Unnever, Nicole L. Piquero and Jill A. Gordon. 2010. “Never too Late: Public Optimism about Juvenile Rehabilitation,” Punishment & Society. 12(2): 187-207. Examines preferences for public policy associated with juvenile crime.

Laurence Steinberg. 2009. “Adolescent Development and Juvenile Justice,” Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 27(3): 307-326. Summarizes findings on brain, cognitive, and social development in adolescence and discusses implications for juvenile offenders.

Comments 17

glenda cody — June 21, 2013

I am curious about information from the lifers club on a teddy bear I got in an auction in portland Oregon in 1995, the tag says it was made by someone in the OSP Lifers club. and it list OSP as being at the original location on State Street in salem Oregon. any info would be great.

A positive mind and outlook on life no matter how dismal, and bleak a future may look will always prevail.

No matter what the woes of the past, the future is still yours no one can take away your tomorrow, besides GOD himself..

glenda cody — June 21, 2013

in approximently 1995 I got a teddy bear from an auction in portland Oregon the tag says it was made at the OSP by a member of the Lifers club the address on the tag lists OSP at the original address in Salem, is it possible to find out who might of made this bear and when. any information you could possibly refer me to would be much appreciated .

L.P. — September 17, 2013

I was on Trevor Walraven's jury so many years ago.

Often I have thought of him and wondered what he was doing with his life. Guilt does not spur my curiosity; it is more like a feeling of responsibility because of my involvement with the verdict in his case.

This article makes it seem like both brothers are trying to make the most of their lives and their time in prison, which is a positive thing. I am disturbed, however, by the quoted section wherein Trevor discusses how long he should be incarcerated. I was expecting more regret, remorse and introspection, instead of criticism of the legal system.

Trevor Walraven got less of a sentence than he could have been dealt, but prisoners usually do not look at the ways the justice system has helped them. If he is a better person now than he was before, that is another positive effect of prison. People who only get worse in prison are the ones who do not accept responsibility for their actions.

I hope both brothers have accepted responsibility for their roles in the death of Bill Hull, and I hope they have prosperous lives now, and when they are released from prison.

Taylor — November 10, 2013

Shocking to me that josh had been portrayed as a wonderful human being. He not only has been reprimanded for his unsavory way with his wife. He also said that he likes to stay out of prison drama . Total crap ... I know some of the people he hangs out with and they are nothing but drama. As for his wife.... Well as far as I know this is her second prisoner to be married to. These are just a few examples of why most prisoners are full of crap. Josh Cain is a disgrace for portraying him self in this light . And his wife is a downfall not a blessing .

Anonymous — January 6, 2014

I grew up with the Father Doug Walraven in So Cal. I know he passed away from Cancer during or right after all of this. Know his family and they were all good people. He must have been broken hearted over this situation with his sons. Doug would have never done anything like this when he was a young boy. So sorry for all especially the victims family. Glad to see some good is going on with these boys in prison. Very tragic.

Steve Smith — April 15, 2014

I did time at OSP with these guys and know them well. They have grown into fine young men.

The comment about Josh being fake are from an outsider looking in. The phone calls commented on were private fantacy phone calls between a man and his wife and no ones business. These comments were obviously made by a disgruntled corrections officer who hates incarcerated individuals as a whole as witnessed by his general "most prisoners" comment and the fact he was even aware of the phone calls.

Both work very hard at bettering themselves and those around them.

I have personally cried with them over the guilt they feel for the pain their actions have caused.

To place any blame on their family is wrong. They had wonderful parents.

L.P. — June 24, 2014

To Anonymous Also - I read the article very closely, I assure you, and I stand by my opinion. As for your other comments, Trevor Walraven is only a victim of his own choices. The first victims are Bill Hull and his family, and the secondary victims are these young men's families. Additionally, I do not believe that $15,000 is an unreasonable amount for a fine after serious felony convictions.

I do believe rehabilitation is possible, but it can only come with taking full responsibility, and I do not see that here. What I see here, in a nutshell, is "I am working to better myself, but this is still not fair for me." That is not enough, and it certainly doesn't sound like remorse. In fact it doesn't mention the real victims at all.

Anonymous Also — September 14, 2014

Yes, it was brought up and factual that he has earned somewhere in that amount since 2005, hardly the past FEW years. It was also brought up that this amount has been earned working 14 to 18 hours per day, every day.

You can check for yourself and see, his restitution as well as his brothers are paid in full. So eager are you to speak of that which you do not know!

You say no remorse and no restitution paid, and in both you are so wrong, you speak of that which you know nothing at all.

It is better to not speak at all and to appear ignorant, than to speak and remove all doubt! Exactly what you are doing here. You really should know that facts before you go public with falsehoods.