Reading the Biden administration’s “plan to build modern, sustainable infrastructure and an equitable clean energy future,” one is easily impressed. Biden’s “Build Back Better” plan is an ambitious legislative package that contains provisions for an array of goals, ranging from COVID-19 vaccine distribution to tax credits for American workers. The “American Jobs Plan,” phase two of Build Back Better, endorses many of the ideas put forward by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) and Senator Ed Markey (D-Mass.) in their “Green New Deal” agenda. Both the campaign and White House websites seem to embrace the idea that a strong federal government should serve as a mechanism to protect, serve, and provide for those living in the United States. The plan, of course, strives to curb the effects of climate change. And importantly, the Administration aims to improve the country’s aging transit infrastructure. This includes updating public transportation options, using “clean energy,” creating millions of jobs and training opportunities in the process. Strikingly, the administration acknowledges the socially unjust public health consequences of polluting practices and climate change – something social scientists have been stressing for decades, which has been at the heart of the recent wave of Green New Deal proposals.

As sociologists who consider how environmental, economic, and public health concern about hydraulic fracturing (better known as fracking) affects public opinion, we found it encouraging that the Biden Administration’s plan acknowledges the danger of abandoned but unplugged oil and natural gas wells, which can leak toxic chemicals into local water supplies, among other social and health consequences. And yet, there is no specific mention of hydraulic fracturing or unconventional natural gas or oil extraction in the Biden Administration’s plan. Currently, and in spite of the risks, federal regulation of fracking is minimal. Moreover, because fracking is exempt from existing federal regulations like the Clean Water Act, it is puzzling that a president touting the importance of public health would only indirectly raise the issue of abandoned wells when active drill sites are commonly known to cause public health problems. In this article, we outline the risks of fracking and continued dependence on natural gas, arguing that if public health is indeed a priority for top politicians, the U.S. public must hold the current administration accountable on the issue of fracking regulation. Biden’s commitment to public health and the desire to “Build Back Better” may represent an opportunity for activists, NGOs, and other organizations if they can successfully frame fracking as a public health risk.The Risks and Regulation of Fracking

Admittedly, fracking is not at the forefront of many political discussions. Even at the height of national coverage in the early 2010s, 39% of Americans reported that they had never heard of hydraulic fracturing. Despite this inattention fracking comes with significant risks. Hydraulic fracturing is a process in which wells are drilled into shale bedrock before a mixture of water, sand, and chemicals is injected into the bedrock at high pressure. This injection into the rock strata releases natural gas and other fossil fuels. Compared to other extractive industries, fracking is subject to little oversight, despite the use of toxic chemicals known to contaminate local water supplies and negatively impact air quality, much to the detriment of local public health, as sociologists and other scholars have documented. Proponents of fracking argue this practice can be done safely and that it poses minimal risks to surrounding communities. Meanwhile, opponents of fracking point to numerous cases of air pollution, water contamination, and even earthquakes.

Although there has not been a large-scale effort to track and compile cases of contamination and pollution for the U.S. as a whole, regional data show cause for alarm. For example, a report from the Environment America Research and Policy Center notes that Pennsylvania alone confirmed at least 260 instances of private well contamination between 2005 and 2016. The same report notes that “Researchers with the Environmental Protection Agency have identified 457 spills in 11 states caused by fracking operations from 2006 to 2012 and concluded that this likely undercounts the actual number of fracking spills. Meanwhile, as Alexander Sammon reports, the number of new and newly orphaned fracking wells continues to grow. These dry wells often go unplugged due to expense, posing further risk of groundwater, soil, and air pollution, with unplugged wells known to “spew everything from crude to methane to brine.”

Fracking has also been linked to poor air quality through venting of the wells and harmful emissions from site machinery and vehicles, which exposes local residents to volatile organic compounds (VOCs), such as benzene, xylene, and toluene. These VOCs are associated with a range of health concerns, including eye irritation, headaches, asthma, and cancer. Still more, the fracking industry has contributed significantly to climate change. Despite attempts to frame natural gas as a “bridge,” or “clean” fuel to more sustainable energy production due to its comparatively low greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, these claims remain dubious, as active and abandoned wells often emit methane, which is an especially potent GHG.

Despite these known risks to public and environmental health, regulation of fracking and the industry is largely overlooked at the federal level. In fact, as previously mentioned, fracking remains exempt from existing environmental regulations, including the Clean Water Act, Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, the Hazardous Material Transportation Act, and the Emergency Planning and Community Right to Know Act, a clear failure of environmental federalism. At the state level, New York has banned the practice of fracking, but political scientist Jeffrey Cook notes that they remain an exception, “over 20 states have actively promoted the development and use of fracking technology.” Even as some state legislatures work to regulate fracking, the “industry has always been influential in these respects because of its deep pockets and wealth of technical knowledge,” preventing regulation. This economic and intellectual influence are hallmarks of the fossil fuel industry; they have aimed to shape the ideologies of politicians and public opinion in their favor, as several sociological studies convincingly demonstrate.The Importance of Public Opinion

Powerful industry actors and lobbying firms have considerable influence on policy making in the United States and have worked hard to secure protections from regulation, and their sway in Congress and within presidential administrations certainly presents challenges to future regulation. However, the Biden campaign has made a commitment to public health and environmental justice. Now may be an ideal time for activists, NGOs, and community organizations to advocate for stronger fracking regulation. Policy regulating fracking is linked to public opinion, and while not universally true, public opinion tends to have a substantial impact on public policy, including fracking policy. In comparison to the U.S., for example, concern over fracking in Europe and the UK is quite high, and in turn, regulations on fracking are stricter. What is more, there is variation within Europe, with the strictest regulations and outright bans on fracking existing in the countries exhibiting the highest levels of concern.

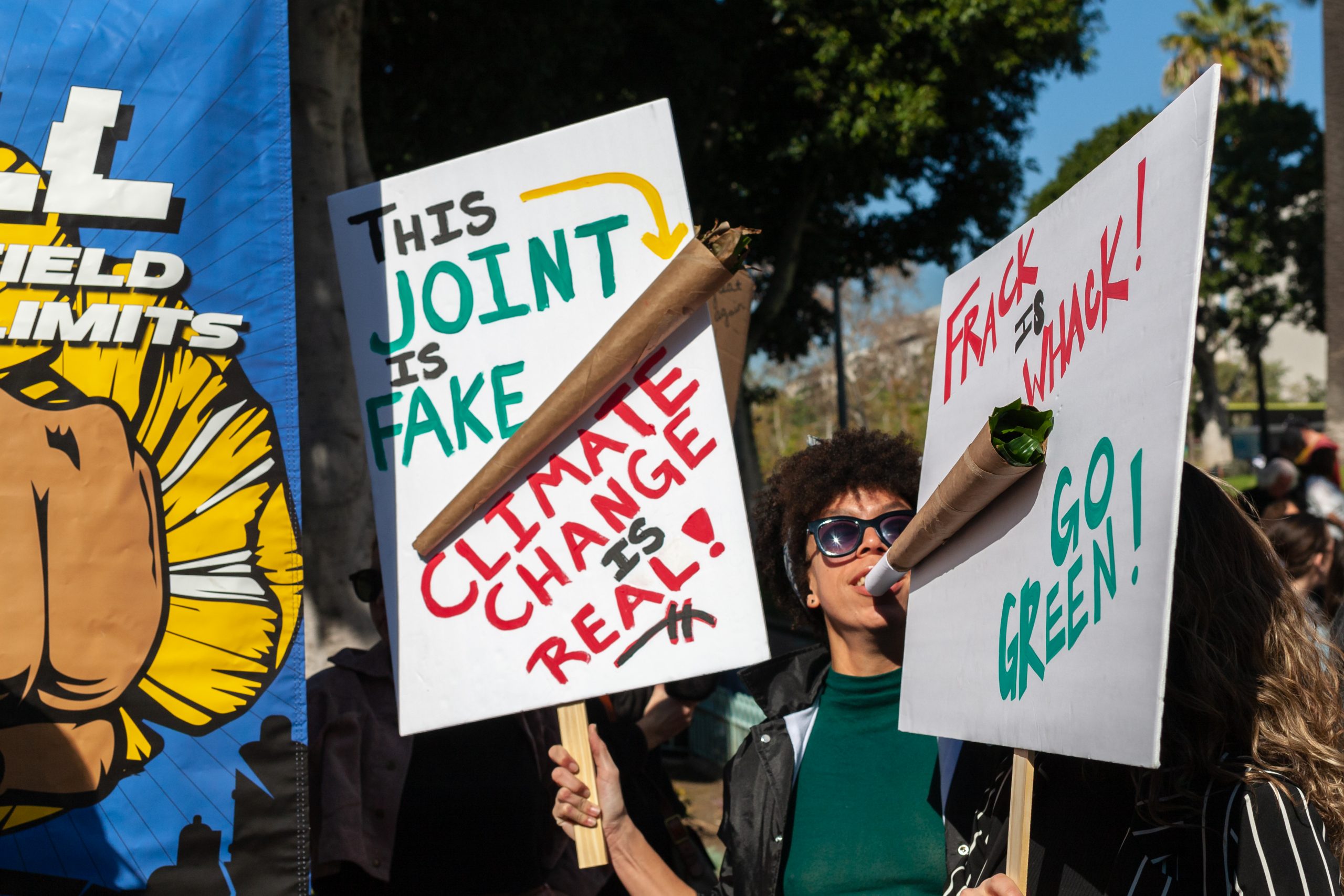

Thus, there are at least two encouraging signs that the oil and gas industry may be called to account in the coming years. First, history demonstrates that local and state movements against the fracking industry can be productive in the U.S. For example, we have seen the successful ascent of the Sunrise Movement, Extinction Rebellion, and Jane Fonda’s popular Fire Drill Fridays (Figures 1 & 3). These have placed pressure on “moderate” Democrats like President Joe Biden (D) and Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) “to make climate change an urgent priority across America” and “end the corrupting influence of fossil fuel executives on our politics.” Indeed, activists have recently partnered with prominent progressives like Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.), and Rep. Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.). More specifically, we have seen successful local movements against the fracking industry. “Frack Free Denton [TX]” is the most notable of these local movements and resulted in a fracking ban in the city despite heavy investments in an industry counter-campaign – although it is worth noting that local regulation of extractive industry was soon after nullified by the Texas state government.

Moving forward, scholars and activists might usefully look at environmental issues like fracking with a transnational lens. To date, American sociologists have produced a rich body of empirical research based upon both quantitative survey data, as well as in-depth qualitative work, to examine the consequences of fracking, its community impacts, and the role of public opinion in its regulation. This scholarship has provided a strong basis for contesting the industry-touted benefits of fracking. However, we need to place the U.S. in relation to Europe and the UK, where fracking activism has been robust in recent years. The possibilities for unifying research across national contexts remain an open question, but doing so my help anti-fracking organizations, activists, and policy makers learn from European successes.

Looking Ahead

Commenting on past incarnations of Green New Deals, Political scientist Timothy Luke has remarked that there remains a deep disconnect between the “romance” of the New Deal and FDR’s Keynesianism and its actuality. Luke warns that “taking the New Deal as a policy black box without weighing its contents…is an easy rhetorical turn that its present-day proponents would simply have us paint all over with ‘green’ initiatives.”

It remains to be seen what Joe Biden, anointed as the 21st century FDR, will do. Rep. Ocasio-Cortez (Figure 6) and others seem to recognize that progressive policy agendas need to make a difference for communities of color, remedy long standing problems related to the decaying industrial core of America, and address environmental injustices. We argue the task ahead is twofold. First, journalists, scholars, activists, and other stakeholders must continue to collect and promote information that emphasizes the public health risks fracking poses to local communities. It bears repeating that understanding fracking as a public health concern is significantly correlated with opposition to the practice of fracking. However, awareness alone will probably not enact policy change. As sociological research has shown, industry, and especially the fossil fuel industry, remains a powerful force in American culture, politics, bureaucratic policymaking, and implementation. Indeed, the environmental movement needs to remain attentive to the forces in American conservatism that see the Green New Deal as “America’s OFF switch” (Figure 5).

It remains to be seen what exactly the forthcoming infrastructure plan will finally include. However, recent White House press releases still do not prioritize the problems posed by oil and natural gas extraction. All the same, the deepening footprint fracking leaves on our environment (Figure 2) – air, soil, and water – was not going to be erased with the stroke of Biden’s pen. Federal legislation is needed in order to have uniform health and environmental protections. To achieve this fracking must become a priority for Americans and a sustained point of conversation in the public sphere. This feat will likely only be accomplished with the leadership of a coalition of social movement organizations, NGOs, community organizers, journalists, and interdisciplinary scholars. The failure to specifically name the fracking industry in the Biden Administration’s infrastructure and energy plan is notable, and the administration likely will not make fracking regulation a priority unless it registers as such with voters. However, a president who campaigned on his own version of the Green New Deal and who has made public health promises to an electorate to an electorate known to take matters of public health seriously may mean that the Biden Administration will feel pressure to better regulate the fracking industry at a critical time in our global history.

Suggestions for Further Reading

“Public Opinion is Moving Against Natural Gas and Fracking.” 2021. Sightline Institute, sightline.org.

“Most Americans Support Reducing Fossil Fuel Use.” 2019. Gallup.

Brian F. O’Neill and Matthew Jerome Schneider. 2020. “A Public Health Frame for Fracking?” The Sociological Quarterly

“Fact Sheet: President Biden Announces Support for Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework.” 2021. White House.

“In Slumping Energy States, Plugging Abandoned Wells Could Provide An Economic Boost.” 2020. Pew Trust, Stateline.

“Biden’s Promising, Problematic Plan to Plug Orphaned Oil and Gas Wells.” 2021. American Prospect.

“Special Report: Millions of Abandoned Oil Wells Are Leaking Methane, a Climate Menace.” 2020. Reuters.

“Fracking By The Numbers.” 2016. American Frontier Group.