The politics of respectability, that elusive set of guidelines that dictate how racialized Americans ought to conduct themselves in public, were complicated recently when a 69-year-old Asian American doctor was forcibly dragged off a United Airlines flight.

The video of Dr. David Dao’s limp body being hauled off the plane provoked international outrage, especially from Asian Americans, but some argued that race had nothing to do with the incident — that the same level of outrage would have followed regardless of the passenger’s race.

Two questions immediately come to my mind.

First, would this have happened to Dao if he was white? The politics of respectability would render a senior, white male doctor as worthy of deference and respect. Second, would cries of outrage have been as loud if the man dragged off the plane was African American? The surge in violence against black people in the last decade, and the generalized indifference to it until recently, suggests that would be unlikely.

In Dao, Asian Americans like me could identify their own elderly fathers, and we shuddered at the thought that our family members could have been victimized in the same horrific manner.But I doubt that non-Asian Americans saw their fathers in Dao. Instead, what they may have seen is the personification of an Asian American trope — the model minority. As an Asian American doctor, Dao embodies the popular narrative that Asian Americans are highly educated, hard-working, committed, successful and deserving. This facile veneer, however, obscures more than it clarifies about Asian Americans.

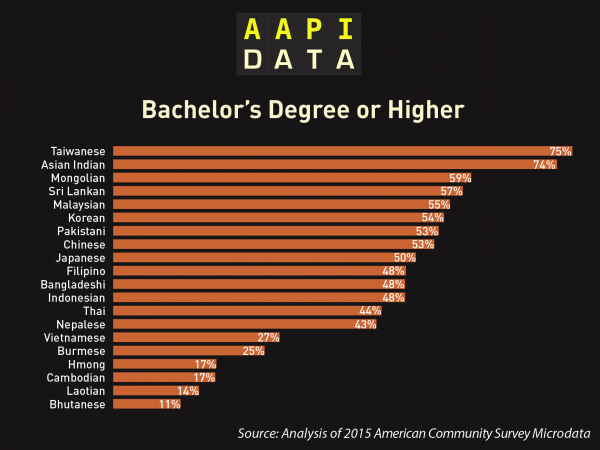

Comprised of 24 detailed origins, Asian Americans exhibit more socioeconomic diversity than any other U.S. racial group. Take educational attainment for example. While half of Asian Americans have a B.A. or higher, the proportion jumps to three-quarters among Taiwanese and Asian Indians. At the other extreme are groups like Cambodian, Laotian, and Hmong—about one-third of whom do not graduate from high school.

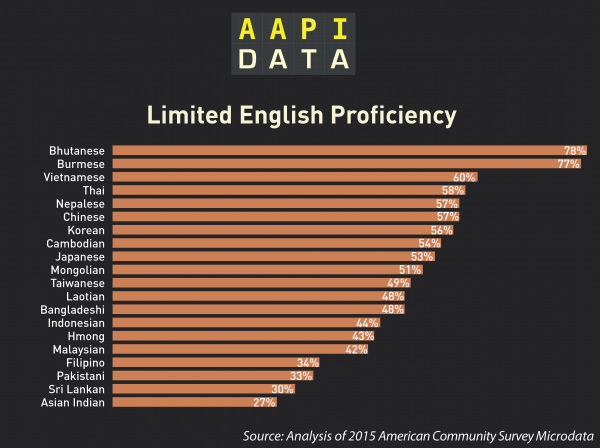

Moreover, at 35 percent, Asian Americans have the highest rate of “limited English proficiency” (LEP) among all U.S. groups. This figure, however, masks their heterogeneity; 60 percent of Vietnamese are LEP, as are 57 percent of Chinese, and 56 percent of Koreans. By contrast, the LEP rate is only 27 percent among Asian Indians.

These differences are critical because they affect life outcomes like health, earnings, and civic participation, including voting. The model minority trope, however, masks these differences and erases the ethnic, economic, and social diversity among Asian Americans.

As vociferous as social scientists have been in debunking the model minority trope, it continues to reemerge in popular discourse. Most recently, in New York Magazine, Andrew Sullivan invoked it to explain the rise of Jews and Asian Americans. Sullivan writes,

“Asian-Americans, like Jews, are indeed a problem for the ‘social-justice’ brigade. I mean, how on earth have both ethnic groups done so well in such a profoundly racist society? How have bigoted white people allowed these minorities to do so well — even to the point of earning more, on average, than whites? Asian-Americans, for example, have been subject to some of the most brutal oppression, racial hatred, and open discrimination over the years … Yet, today, Asian-Americans are among the most prosperous, well-educated, and successful ethnic groups in America.

What gives? It couldn’t possibly be that they maintained solid two-parent family structures, had social networks that looked after one another, placed enormous emphasis on education and hard work, and thereby turned false, negative stereotypes into true, positive ones, could it? It couldn’t be that all whites are not racists or that the American Dream still lives?”

The trope endures, even in spite of the disconfirming evidence. The poverty rate among Hmong and Cambodians is 29 percent and 21 percent, respectively — far higher than the U.S. national average at 13.5 percent. Moreover, one in seven Asian immigrants is undocumented, and Asian undocumented immigrants account for about 14 percent of the undocumented population in the United States.

While many Asian Americans do not fit the model minority stereotype, the narrative persists, in part, because individuals have powerful, largely unconscious tendencies to remember people, events, and experiences that confirm their prior expectations. So strong is this tendency that we often fail to see Asian Americans who are poor, undocumented, or have dropped out of high school. And even when we do see them, we reinterpret the information in stereotypic-confirming ways, ignore it, or dismiss it altogether as the exception, resulting in a cultural lag between material realities and our interpretation of them.

In addition, by coupling the model minority trope with the American Dream, Sullivan concocted a recipe that is seductively potent, yet fallacious. The ideology of the American Dream — that any individual, regardless of how humble his/her origins, can make it — is premised on America’s legacy of immigration, which conveniently ignores its ugly twin legacy of slavery. Individualism, meritocracy, and grit are the pillars of the American Dream, which continue to be lauded in public discourse by popular examples of immigrants and ethnic minorities who have “made it.” The exceptions prove the rule that the American Dream works, and the specious evidence is used to divide the deserving from the undeserving.Returning to the politics of respectability and model minority trope, how do these help us understand our collective outrage at United’s inexcusable treatment of Dao?

In early news reports of this story, there was no mention of Dao’s race or ethnicity. As the video began to circulate, however, one could easily discern that the passenger was Asian American, and based on first sight, people assumed that he was Chinese American. That Dao is a Vietnamese refugee did not diminish the outcry, nor did it change our view that he is deserving of our outrage, empathy, and support. But would it change if Dao was Hmong, whose group position in the Asian ethnic hierarchy is lower than that of Chinese and Vietnamese?

Moreover, would we have been just as outraged and empathetic if Dao were African American or a recent immigrant from South America? Imagine the possibility if we were just as vociferous about the recent videotaped deaths of African Americans at the hands of police officers, or the forced deportation of DREAMer Juan Manuel Montes. Indeed, there is outrage from certain segments of the population, but nothing that matches the immediate, unwavering, and uniform support for Dao. Even when the media began a smear campaign against him, the public rejected it as irrelevant.Without question, Dao deserves our outrage, empathy, and support, and kudos to the masses that demanded it. But just as deserving are individuals of other racial and ethnic backgrounds, ages, and socioeconomic statuses who lack the protection of visible status markers that deny them the same degree of public respectability.

Recommended Readings

Patricia Fernandez-Kelly. 2016. “Fixing the Cultural Fallacy.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39(13): 2372-2378.

Jennifer L. Hochschild. 1996. Facing Up to the American Dream. Princeton University Press.

Jennifer Lee and Min Zhou. 2015. The Asian American Achievement Paradox. Russell Sage Foundation.

Karthick Ramakrishnan and Sono Shah. 2016. “One Out of Every 7 Asian Immigrants Is Undocumented.” AAPIData.

Sono Shah and Karthick Ramakrishnan. 2017. “Why Disaggregate? Big Differences in AAPI Education.” AAPIData.

Ellen D. Wu. 2014. The Color of Success. Princeton University Press.

This article was adapted from “Politics of Respectability and a Dragged Passenger,” by Jennifer Lee, NPR Code Switch, April 14, 2017.