Faith in law enforcement — police and prosecutors — has faltered in the wake of unjustified police shootings and the lack of accountability taken by the officers involved. As Brian Forst argues, the unjustified killing of an innocent person is an egregious “error of justice,” but so too is unjustified incarceration. In their study of death row exonerees, Saundra Westervelt and Kimberly Cook show how wrongful incarceration can lead to social, psychological, and financial problems for exonerees including depression, poverty, estranged family relationships, health problems, and more. But many prosecutors understand the gravity of wrongful convictions and work hard to avoid them. Their good faith efforts to rectify wrongful convictions can both assist the exonerated and increase criminal justice system legitimacy at a time when community relationships are at risk.

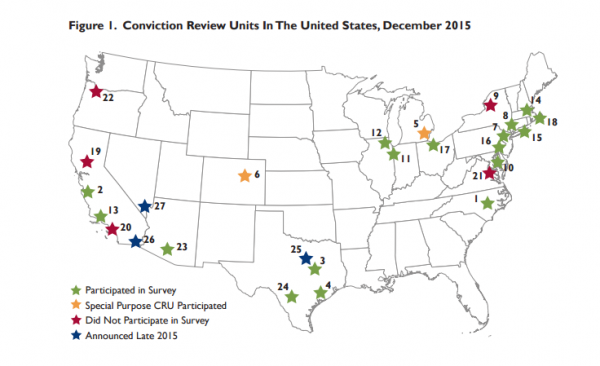

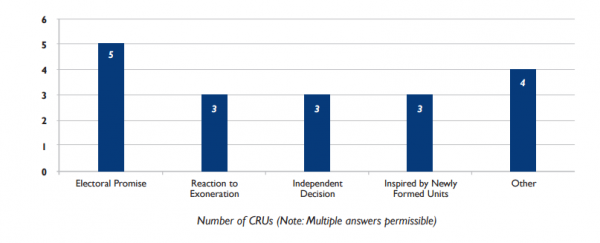

For example, district attorneys can create “Conviction Review Units” (CRUs) that investigate wrongful conviction claims — with all of the power and resources that the state brings to bear. CRUs, also known as conviction integrity units, can either collaborate with innocence projects and other defense attorneys, or identify cases and review them independently. When a defendant’s claims are deemed credible, the district attorney can exonerate them by dismissing the case. The key question for social science research is whether these CRUs are effective remedies or whether they simply legitimize the behavior of prosecutors. New research on this question provides clues about what to look for when evaluating a CRU.According to a recently released report from the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice, 27 CRUs exist today, mostly in large cities like Brooklyn, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Houston —communities that had already weathered a number of exonerations before CRUs came into existence. Craig Watkins, Dallas County’s first African American district attorney, is often credited with creating the first large-scale, successful CRU in 2007 to address a series of wrongful convictions in his jurisdiction. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, CRUs have helped exonerate about 200 people since 2003 (as of August 2016). CRUs are one way of restoring public trust in district attorneys, who represent the state in prosecuting criminal offenses. Still, some have fallen short of delivering on the promise of “integrity” that the name implies.

CONVICTION REVIEW UNITS and SYSTEM ACCOUNTABILITY

Prosecutors often have great latitude and discretion in deciding whether and which criminal charges to file, whether a case will be eligible for the death penalty, whether to pursue mandatory minimums, and other charging and sentencing decisions. The prosecutor’s power to decide whether to charge police officers with allegations of police brutality represents an especially prominent example of such discretion. When researchers discuss the potential for prosecutorial abuse of power, these are often the types of decisions they have in mind. Another overlooked source of discretion is the prosecutor’s power to decide how to respond to claims of wrongful conviction. Legally, prosecutors are not required to cooperate with the defense when post-conviction evidence of innocence arises, or to re-investigate problematic convictions.

The Innocence Project estimates that an exoneration case takes “between a year and a decade” from the time of case acceptance to the official exoneration. Much of that time will be spent seeking the prosecutor’s cooperation, which might involve consenting to post-conviction DNA testing or considering other new evidence of innocence. Whether the exoneration takes a year or a decade — or whether it is successful at all — often depends on the prosecutor’s willingness to cooperate. Stubborn prosecutors may dig in their heels indefinitely, spending tax dollars to fight the innocence claim and prolong the period of unnecessary incarceration or supervision. But why would prosecutors be uncooperative? Social science research shows that prosecutors make decisions based on a whole host of criteria, including professional advancement, maintaining good working relationships, efficient processing of cases with limited resources, and even stereotypical assumptions about the case or the defendant.WHEN ARE CRUs EFFECTIVE?

The Quattrone Center report, “Conviction Review Units: A National Perspective,” sheds light on the question of how to evaluate the effectiveness of a CRU. Released in April 2016 and authored by the Center’s Executive Director John Hollway, the study is based on semi-structured interviews and surveys with the heads of 19 CRUs. The Dallas CRU, as well as most of the nation’s established CRUs, participated in the study.

Barry Scheck, co-founder and co-director of the Innocence Project, makes similar recommendations in a 2010 law review article advocating for conviction integrity units. In his vision, the criminal justice system seeks to improve “quality assurance” much like a business would. Rather than rushing to assign blame for errors, the system acknowledges them and learns from them. Hollway shares this vision of “a culture of relentless and objective self-improvement” in which CRUs identify wrongful convictions, learn from them, and then rectify the underlying issues.

The Quattrone Center report concludes that most of the CRUs participating in the study represent sincere efforts to uncover unjust convictions. Nevertheless, Hollway also suggests that some are nothing more than “CRINOs” or, Conviction Review In Name Only, that fail to deliver independence, flexibility, and transparency. He argues that an illegitimate CRU is worse than none at all. Such CRINOs create a false sense of legitimacy, reinforce the status quo, and fail to address the real problem of wrongful convictions.

As both Hollway and Scheck point out, a criminal justice system that minimizes and hides its errors will never learn from them. Nevertheless, there is an underlying tension in asking prosecutors to change longstanding practices and to play a larger role in exonerating those they convict. The very existence of a CRU is therefore an important system innovation and, perhaps, the sort of innovation that will reduce system error and improve the quality of justice.

Recommended Readings

Brian Forst. 2004. Errors of Justice: Nature, Sources and Remedies. Cambridge University Press.

Bruce Frederick and Don Stemen. 2012. “The Anatomy of Discretion: An Analysis of Prosecutorial Decision-Making.” Technical Report. New York: Vera Institute of Justice.

John Hollway. 2016. Conviction Review Units: A National Perspective. University of Penn Law School. Public Research Paper.

Barry Scheck. 2010. “Professional and Conviction Integrity Programs: Why We Need Them, Why They Will Work, and Models for Creating Them.” Cardozo Law Review 31(6).

Saundra D. Westervelt and Kimberly J. Cook. 2012. Life After Death Row: Exonerees’ Search for Community and Identity. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Comments