The growth and development of interdisciplinary happiness studies has been encouraging, fascinating, and useful. However, the flower of happiness is still in bud and has not yet blossomed. When it does, happiness will be replaced with joy. In the words of existential psychologist Rollo May,

“Happiness depends generally on one’s outer state; joy is an overflowing of inner energies and leads to awe and wonderment. Happiness is the absence of discord; joy is the welcoming of discord as the basis of higher harmonies. Happiness is finding a system of rules which solve our problems; joy is taking the risk that is necessary to break new frontiers.”

As the field of positive psychology has grown since 1998 (following Martin Seligman’s chosen theme for his presidency of the American Psychological Association), we increasingly recognize and understand the psychological desires for and multiple benefits of what is often termed “happiness,” and less commonly termed “human flourishing,” “well-being,” “fulfillment,” and “joy.” Likewise, with the biology of happiness, we continue to isolate and identify the happy gene (i.e., a particular gene on the third chromosome), the happy nerve (i.e., vagus nerve), and the happy hormone (i.e., oxytocin).

Even if, as has been asserted, genetics accounts for half of our happiness, the other half may be social and therefore can be learned, practiced, nurtured, and increased. Genes, nerves, and neuropeptides aside, we may very well be responsible for and be able to adjust considerably more than half our happiness and joy — it depends on how we interact with each other. Perhaps instead of positive psychology, baseline biology, or neverland neurology, we can call this the social scientific subfield of serendipitous sociology!

As Jeremy Adam Smith realizes, “Many of the same biological and psychological mechanisms that bond us together can also tear us apart. It all depends on the social and emotional context.” Whatever nature exists, nurture can typically override it. Or as Paul Zak states, “We do have to be in the right environment to be virtuous.” Societies that encourage pro-social behaviors are societies with more pro-social behaviors — and vice versa. It appears that we are less biologically and psychologically determined than we are socially capable, as anthropological, primatological, and sociological studies across time and place repeatedly suggest.

What has generally been missing in the overly-individualistic fields of psychology and biology, and to a certain extent economics, however, is a sociology of joy that properly situates happiness in social contexts as both cause and consequence of certain relational behaviors between and among human beings — and others. These social phenomena include: gratitude, kindness, sympathy, empathy, compassion, respect, social connections, camaraderie, solidarity, play, gatherings, music, stories, comedy, arts, games, flirting, love, sex, generosity, service to others, and many more. There are also various non-human interactions with animals, nature, culture, and our built environment, for example, that can do this, as well. “Happiness, it turns out, is not as much inside the head as we had thought”, as UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center Co-Director Dacher Keltner concludes. “It’s really about making other people do well. That’s the core idea of the meaningful life.”

Each of these phenomena (as well as certain phenomena associated with unhappiness, such as resentment, hostility, embarrassment, humiliation, shame, shunning, ostracism, social anxiety, betrayal, grudges, schadenfreude, crime, violence, vengeance, terrorism, and war) are relational and therefore can only occur in social relationships, not simply within one’s individual pysche, brain, or body, as psychology and biology might imply. These phenomena cannot be solely situated within the mind or body, as they transcend the individual and always occur in a social context. This is why happiness is defined differently in different times and places, and different countries and cultures, just as happiness manifests in different ways across time and space.

This is not to deny the importance of biology and psychology — to do so would be overly simplistic and foolish — but to understand their limitations and thereby complement them with sociology. As Robert Sapolsky explains, “The action of genes is completely intertwined with the environment in which they function; in a sense, it is pointless to even discuss what gene X does, and we should consider instead only what gene X does in environment Y.” Siddhartha Mukherjee argues similarly in his brilliant book The Gene. This is sometimes referred to as epigenetics, though Mukherjee doesn’t care for the term. Likewise, sociologist Jason Schnittker concludes that there is “ample evidence that both happiness and the environment are influenced by genetic factors and family upbringing.”

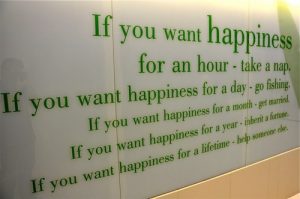

Although undoubtedly easier for some than others, Leo Tolstoy suggested that “If you want to be happy, be.” Around the same time, Abraham Lincoln noted that “Most folks are as happy as they make up their minds to be.” Of course, happiness and joy do not have to be all-or-nothing binaries that necessarily require a complete change of personality, circumstances, or life. Indeed, Google’s former happiness guru, Chade-Ming Tan, discovered that one could grab onto what he calls “thin slices of joy” from the daily mundane and too-often overlooked details of life: a blue sky, a beautiful flower, a nice breeze, a delicious taste, a sip of water, a fond memory, and infinitely more. Tan reminds us that these “thin slices of joy” are potentially omnipresent and that the more we try to notice them, the more we will find them — creating a positive habit — and the more we will be rewarded with instances of micro-happiness that will add up to a more joyful life.

Yet, we recognize that happiness is also related to money, to a certain extent, in that people tend to be less joyous if they cannot meet their basic needs, even if they have happy moments. In contemporary American society, levels of joy seem to flatten out at around earnings of $75,000 per year; above that level, we don’t see increases in joy, even though most people believe they would be happier with more money (and would be willing to find out for themselves). Further, it is not simply a matter of earnings, but also one of economic inequality. Happiness, as well as other social indicators, tend to be higher in more equal societies, ceteris paribus, compared to more unequal societies, as Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett detail. Relatively deprived people are generally less happy.

Happiness seems to be related to money in another important and, perhaps, surprising way. Sharing and pro-social spending (i.e., giving money or buying something for another) tends to lead to more and lasting joy than not sharing and engaging in anti-social spending (i.e., keeping money or spending on oneself). Indeed, Sonja Lyubomirsky concludes that doing for others does best for oneself, in terms of both short-term happiness and long-term joy, or what some have called “enlightened self-interest.”

Joy may also be related to social connection, as classical sociologist Emile Durkheim suggests. Being in relationships, being a member of clubs, organizations, or movements, and feeling more connected to society can boost happiness, while the absence of these social connections can cause anomie, alienation, sadness, and depression, with a higher incidence of suicide. One’s status as a victim of racism, sexism, homophobia, or other forms of “maximum hate for minimal reason”, as Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel described it, can also affect levels of sorrow and joy. Creating in and out groups, as well as the discrimination based on those socially-constructed categories, is also inherently social as opposed to individual.

Engaging in the thoughts and behaviors that are more likely to lead to happiness and joy are also correlated, according to various studies, with lower levels of anxiety, depression, and stress, as well as better mental and physical health overall. Kindness and generosity toward others are more likely to lead to happiness and joy, which is then more likely to lead to more acts of kindness and generosity. This creates a causal cascade (often called a “virtuous circle” or a “positive feedback loop”) of attitudes and behaviors.

Further, many psychologists worry that “positive psychology has been too negative about negativity and too positive about positivity.” Happiness does not really have any meaning without sadness, and joy is unknown without sorrow. Similarly, we cannot conceptualize pro-social behavior if we do not experience and understand anti-social behavior. We therefore need to view our range of emotions more holistically. Additionally, one could have a certain level of happiness from sadness, derive some pleasure from unpleasant — even bad — experiences, which can make for a more holistic, more meaningful, more joyous life.

A trivial example might be not wanting to get caught in the rain, and never purposely choosing nor desiring that scenario. However, despite the wetness, coldness, hassle, inconvenience, need to change clothes, and so forth, there was a sense of adventure, challenge, fun, excitement, and camaraderie. And surprisingly, it was a good and enjoyable “bad” experience that you think of fondly, remember with a certain delight, and tell others about with excitement.

A more serious illustration involves death. For most people, facing the existential reality and inevitability of their own death is not a happy experience. Biologically, psychologically, and culturally, most of us have been conditioned to fear and avoid death. That carries over into our thinking. Discussions of death are not typically located in happiness studies and practices. Yet, recognizing that we are all going to die, just as we were all born, deeply and effectively grappling with and ultimately accepting the concept and actuality of inevitable death, as well as the cultural issues surrounding death, can make us, individually and collectively, less fearful, anxious, and depressed. Indeed, thoughts of death can make us feel more alive. Many Bhutanese Buddhists have taken this approach. Perhaps, paradoxically, properly focusing on death can make us more joyous, even if not necessarily happier in the moment.

Every person is an individual, but no person “is an island”, as John Donne meditatively mused four centuries ago. The late Senator Paul Wellstone (D-MN) said, simply enough, “We all do better when we all do better.” An obvious truism, yet too easily and too often ignored. As much as we are all individuals and may sometimes feel alone in society, we are all in it together and, as Martin Luther King, Jr. so eloquently and poignantly wrote from a Birmingham jail cell in 1963, “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” With respect to us being social — in addition to being individual — there is just no escape. For many of us, that’s a happy development and yet another reason to jump for joy!

Recommended Readings

Dan Harris. 2014. 10% Happier: How I Tamed the Voice in My Head, Reduced Stress Without Losing My Edge, and Found Self-Help That Actually Works. IT Books.

Dacher Keltner, Keith Oatley, and Jennifer M. Jenkins. 2014. Understanding Emotions. Wiley Publishers.

Linda Leaming. 2014. A Field Guide to Happiness:What I Learned in Bhutan about Living, Loving, and Waking Up. HayHouse.

Sonja Lyubomirsky. 2007. The How of Happiness: A New Approach to Getting the Life You Want. Penguin Press.

Rollo May. 199. Freedom and Destiny. W.W. Norton.

Robert Sapolsky. 2004. Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. Holt Paperbacks.

Emma Seppälä. 2016. The Happiness Track: How to Apply the Science of Happiness to Accelerate Your Success. HarperOne.

Ruut Veenhoven. 1984. Conditions of Happiness. Springer.

Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett. 2009. The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. Not Avail.