I just wrapped up my political sociology class for the semester. We spent a lot of time talking about conflict and polarization, reading research on why people avoid politics, the spread of political outrage, and why exactly liberals drink lattes. When we become polarized, small choices in culture and consumption—even just a cup of coffee—can become signals for political identities.

After the liberals and lattes piece, one of my students wrote a reflection memo and mentioned a previous instructor telling them which brand of coffee to drink if they wanted to support a certain political party. This caught my attention, because (at least in the student’s recollection) the instructor was completely wrong. This led to a great discussion about corporate political donations, especially how frequent contributions often go bipartisan.

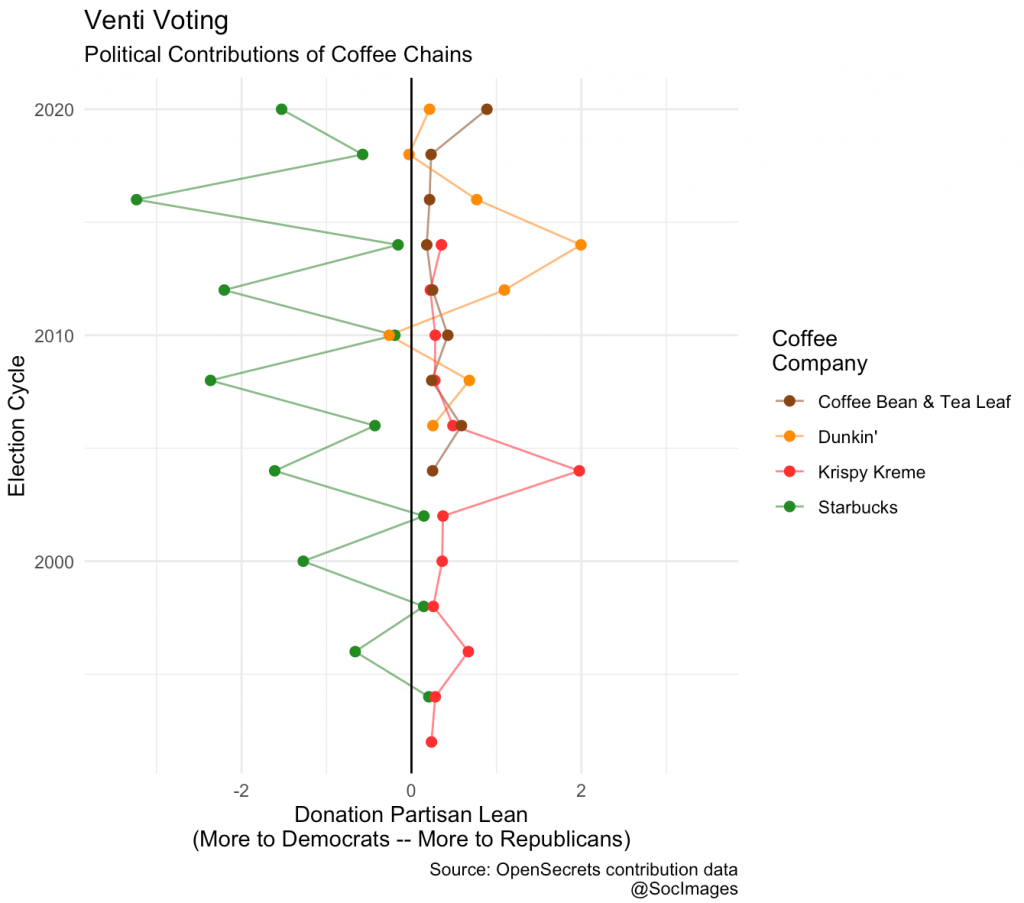

But where does your money go when you buy your morning coffee? Thanks to open-access data on political contributions, we can look at the partisan lean of the top four largest coffee chains in the United States.

Starbucks’ swing to the left is notable here, as is the rightward spike in Dunkin’s donations in the 2014 midterms. While these patterns tend to follow the standard corporate image for each, it is important to remember that even chains that lean one way still mix their donations. In midterm years like 2012 and 2014, about 20% of Starbucks’ donations went to Republicans.

One side effect of political polarization is that corporate politics don’t always follow cultural codes. For another good recent example of this, see Chick-fil-A reconsidering its donation policies.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, on Twitter, or on BlueSky.