It’s International Women’s Day–a day to celebrate the social, cultural, economic, and political achievements of women. It’s a day we often take stock of gender inequality, look at how far we’ve come and where we still need to go. This is a day people in my corner of the world share posts about the gender wage gap, statistics surrounding the enduring reality of violence against women, information about women’s access to health care, and more. It’s a day that sociologists have the tools to make lots of charts.

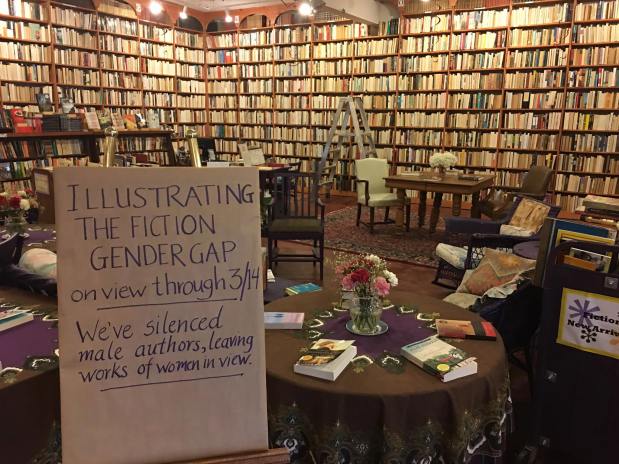

In my feed, sociologist Jane Ward shared a post about a feminist bookstore in Cleveland, Ohio that chose to celebrate Women’s History Month in a unique way: they flipped all of the books written by men in the fiction room of the store around on the shelf. The room will be left that way for for two weeks – through March 14, 2017. Take a look at the result!

It’s a powerful piece of feminist installation art. And it’s sociological. While a sociologist might have produced a content analysis of the room (or genre) and produced a proportion of books written by women, this feels different. They’ve entitled the exhibit “Illustrating the Fiction Gender Gap” and explain the project with this simple sentence: “We’ve silenced male authors, leaving works of women in view.”

They could have simply counted the books and produced figures made available to the public. That’s what most sociologists I know would have done. But something critical would have been missing when compared with the illustration of the gender gap they produced here. Think about it this way: in 2015, the Census calculated that the poverty rate was 13.5% in the U.S. (that was a drop from the year prior). In actual numbers, there were 43.1 million people in poverty in the U.S. that year. Just to think about the size of that group, that’s a number that is basically the same as the total combined state populations of New York, Florida, and Iowa. Can you imagine everyone in all three states being in poverty. That’s the scale of poverty as a social problem in the U.S.

In a similar way, Loganberry Books, produced a really clever piece of feminist installation art to make a reality about literature more visible. It’s different from telling us the proportion of books written by women in the fiction section. In Loganberry, we get to see what that means. If you went in, you could feel it as you looked around. Works by women who be jumping off the shelves, rather than hidden between piles of books by men.

The owner of the bookstore, Harriet Logan, put it this way: “Pictures are loud communicators. So we are in essence not just highlighting the disparity but bringing more focus to the women’s books now, because they’re the only ones legible on the shelf” (here). In an interview with Cleveland Scene, she further explained: “To give the floor and attention to women, you need to be able to hear them. And if someone else is talking over them, that just doesn’t happen.”

It’s a small way of asking the question, What would this corner of the world look like if women’s accomplishments had not been systematically, structurally, and historically drowned out by men’s? What does women’s signal sound like here when we get rid of men’s noise? Books by men are still there. They’re not being banned, removed, or even mentioned as “unworthy” in any way. Men’s books are simply being silenced for two weeks to let women’s work shine. What a powerful, feminist, sociologically imaginative statement.

Happy International Women’s Day!

Tristan Bridges, PhD is a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is the co-editor of Exploring Masculinities: Identity, Inequality, Inequality, and Change with C.J. Pascoe and studies gender and sexual identity and inequality. You can follow him on Twitter here. Tristan also blogs regularly at Inequality by (Interior) Design.