Flashback Friday.

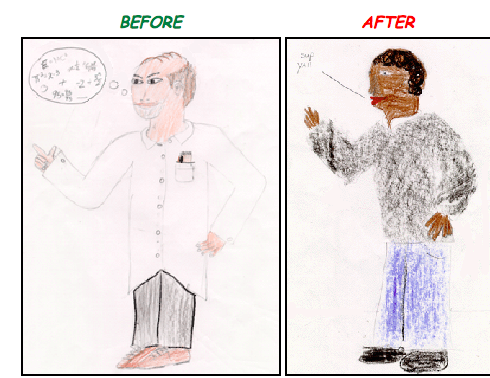

Eden H. sent in an exploratory study about kids’ stereotypes of scientists. The U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermilab asked 7th graders to draw and describe a “scientist” before and after visiting the lab on a class trip. They first read about the Fermilab, then came to the lab and meet with some of the scientists and talk about their work. From the Fermilab website:

What we changed for this field trip was the before and after descriptions and small group sessions for each student to meet with two of three physicists rather than one large group session. We deliberately chose a typical white male, a young female and an African American physicist. We let the students and physicist take their discussion where they wanted.

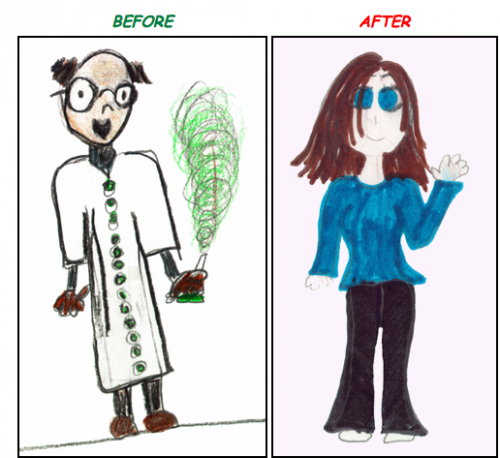

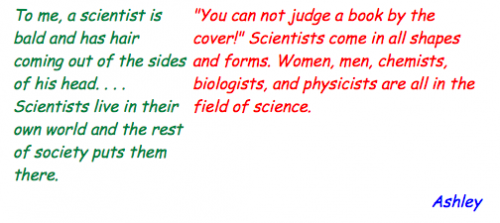

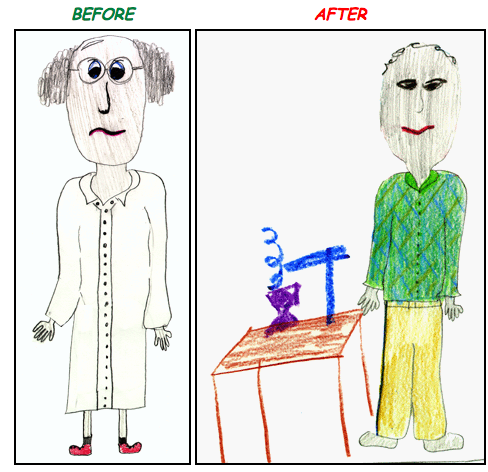

Here are some of the before-and-after pictures and descriptions (all 31 are available here):

In general, the students seemed to come away with an idea of scientists as being more like “normal” people, not just stereotypical geeks in lab coats. But some of the other changes are interesting, too. The author of a post about the study at Restructure! analyzed the before-and-after images (as best as she could identify the sex of the drawings):

- Among girls (14 in total), 36% portrayed a female scientist in the “before” drawing, and 57% portrayed a female scientist in the “after” drawing.

- Among boys (17 in total), 100% portrayed a male scientist in the “before” drawing, and 100% portrayed a male scientist in the “after” drawing.

I looked through all of them and only saw one instance (posted above) where the child changed the scientists to be clearly non-White.

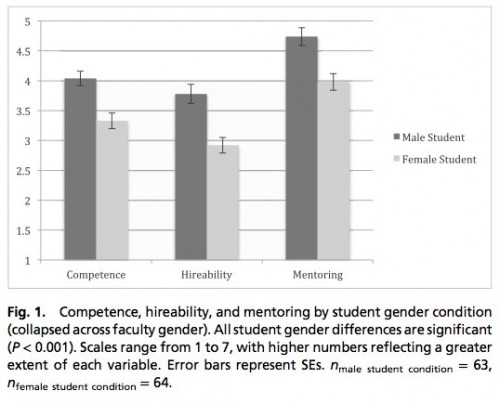

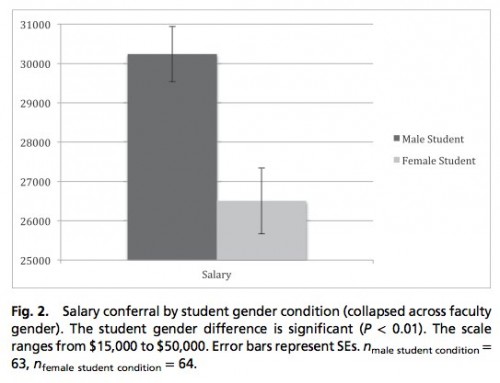

Of course this is a small sample, but the results seem to reproduce what other studies have found regarding the importance of role models and gender stereotyping, in particular, that girls are more likely to imagine themselves in careers when they see women doing them. For instance, the relative lack of female professors in male-dominated departments such as engineering may play a role in discouraging women from choosing to major in such fields (as well as other factors such as steering, concerns about family/work conflicts, etc.).

Originally posted in 2010.

Gwen Sharp, PhD is a professor of sociology and the Associate Dean of liberal arts and sciences at Nevada State College.