Can political leaders put partisanship aside to govern in a crisis? The COVID-19 pandemic has proved to be a crucial test of politicians’ willingness to put state before party. Acting swiftly to slow the spread of a novel virus and cooperating with cross-partisans could mean the difference between life and death for many state residents.

The first confirmed case of the novel coronavirus in the United States was reported in Washington state in January 2020. New cases, including incidents of community spread, continued to be recorded across the country in February. However, federal-level efforts to “flatten the curve” did not begin in force until March. Michigan’s Democratic Governor Gretchen Whitmer was among the first governors to openly criticize the Trump administration’s slow response. Her criticism led to an open partisan feud on Twitter between the two leaders.

In the absence of a national order to limit the virus’ spread within the country, state governors took action. Leaders in states with some of the earliest-recorded cases – such as Washington, Illinois, and California – put stay-at-home or shelter-in-place orders into effect shortly after the US closed its northern and southern borders to non-essential travel. In a matter of weeks, most states’ residents were under similar orders.

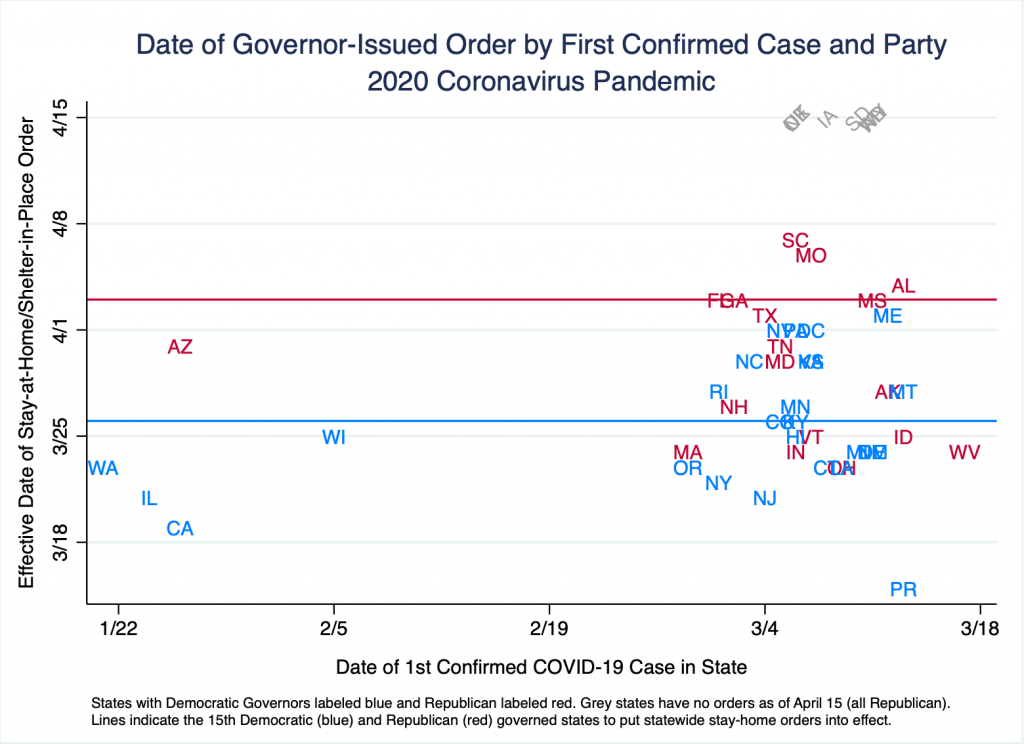

Did governors’ decisions to order their states’ residents to hunker down vary by party? In the figure below, I have plotted the date stay-at-home or shelter-in-place orders went into effect (as of April 15, according to the New York Times) by the date of the state’s first reported confirmed case of COVID-19 (according to US News & World Report). States with Democratic governors are labeled in blue and Republican governors are labeled in red. As of April 15, no statewide stay-home orders had been issued in the Republican-governed states labeled in grey on the plot.

Of the 50 states plus Washington DC and Puerto Rico, a total of 44 governors have issued stay-at-home or shelter-in-place orders. All Democratic-governed states were under similar orders after Governor Janet Mills called for Maine’s residents to stay home beginning April 2. By contrast, just over two-thirds of states led by Republican executives have mandated residents stay home. Eight states – all led by Republicans – had not issued such statewide orders as of April 15, 2020. States without stay-at-home orders have had substantial outbreaks of COVID-19, including in South Dakota where nearly 450 Smithfield Foods workers were infected in April causing the plant to close indefinitely.

Republican governors have generally been slower to issue restrictions on residents’ non-essential movement. Democrats and Republicans govern an equal number of states and territories on the above plot (26 each). Fifteen Democratic governors had issued statewide stay-home orders by March 26. The fifteenth Republican governor to mandate state residents stay home did not put this order into effect until April 3. This move came after all states with Democratic governors had announced similar orders and over two weeks after COVID-19 cases had been confirmed in all states.

The median number of days Democratic governors took to mandate their residents to stay home after their state’s first confirmed case was 21 days. By contrast, the median Republican governor took four additional days (25) to restrict residents’ non-essential movement, not accounting for states without stay-home orders as of April 15.

In short, the timing of governors’ decisions to mandate #stayhomesavelives appears to be partisan. However, there are select cases of governors putting public health before party. Ohio’s Republican Governor Mike DeWine has been heralded as one example. He was the first governor to order all schools to close, an action for which CNN described DeWine as the “anti-Trump on coronavirus.” These deviations from the norm suggest that divisive partisanship is not inevitable when governing a crisis.

Morgan C. Matthews is a PhD candidate in sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She studies gender, partisanship, and U.S. political institutions.

Comments 47

morpheus tv — April 23, 2020

Stop fighting guys.

and check out Morph TV APK. Download Morph TV App on Android Mobiles/Tablets. Install Latest Morph TV 1.69 updated version of Morpheus TV App.

Kristina Barkley — April 25, 2020

News check

Kate — May 6, 2020

Morph TV APK. Download Morph TV App on Android Mobiles/Tablets. Install Latest Morph TV 1.69 updated version of Morpheus TV App. morphtv.me

Morris — May 6, 2020

Since Terrarium TV has been shut down, many apps has been released after that such as Cyberflix, TVZion etc but most of the apps lacks all the feautres which Terrarium was offering. But now Typhoon TV has been released, you can enjoy movies and TV shows without any hassle. typhoontv.in

Libby Howells — May 23, 2020

Can I Pay Someone To Take My Online Class for me? Yes, we're a reliable online class help provider connecting you with subject tutors to take your course & tests.

Lina — June 3, 2020

Great info about Partisanship and the Pandemic.

Shirley — July 2, 2020

Very nicely and in a well described about partisanship and the pandemic topics. Such inspirational and motivational articles can lead you towards success if you are in this situation because students are checking ultius reviews to complete their work. Things are getting better day by day. We should keep trying for a better future. Thanks for sharing.

Typhoon tv apk — July 7, 2020

Thanks for the detailed article, Would love to see more of these.

Manica — July 7, 2020

Thanks so much https://tricksground.com/typhoon-tv-apk-download/

ana tolia — September 29, 2020

In my web dictionary, there are many interesting things. If you are interested, you can experience it subway surfers

chrisgail — October 2, 2020

These images are useful for a marketer because he has to share his services and products on social media for conveying it far from the areas

cheap dissertation writing service

Anna — November 8, 2020

Hello!

It's out of recent character for him but his clearly ornaments diseased mind also tends to the mercurial.

vasil — December 22, 2020

Сейчас среди всех онлайн заработков лучшим является майнинг https://hashalot.io/blog/post_mining/chto-takoe-zcash-i-kak-ego-majnit-na-svoej-ferme-v-pulah-pribylnost-zec/ , по скольку с ним, только ленивый не сможет зарабатывать.

Anonymous — January 28, 2021

Michigan’s Democratic Governor Gretchen Whitmer was among the first governors to openly criticize the Trump administration’s slow response. https://hashalot.io/blog/vse-chto-nuzhno-znat-o-majninge-kriptovalyut-na-radeon-rx-580/

Anonymous — January 28, 2021

The median number of days Democratic governors took to mandate their residents to stay home after their state’s first confirmed case was 21 days. By contrast, the median Republican governor took four additional days https://cryptograph.life/reviews/cryptocurrencies/invest-rassledovanie-monero-xmr-kak-maynit-i-vyvodit-stroenie-i-polza-ot-kripty-ee-perspektivy

โรงแรมรถอุบล — March 14, 2022

this website is really instructive! Keep posting. โรงแรมรถอุบล

ryangary2 — April 15, 2022

UPSers is one of the most extensive delivery services in the USA. United parcel services also give management and logistics services all over the country with the leading supply chain of services. https://upserscom.website/

14CARS.com — June 22, 2022

You can save your time on the way from the airport and rent a car in 14CARS.com . Spend your first trip in the country in a comfortable way.

Helen Mendoza — July 3, 2022

The pandemic was really bad, I still feel like we all have live a decade of jail in our houses with fear of death and problems. In that time, I only passes my time by playing games on my cellphones and chatting with my friends.

Tom3 — July 7, 2022

Have you played fnaf 3? This is part of the game Five Nights at Freddy's (a horror game today) Before starting this game I advise you to prepare mentally to perform your mission. Be the winner!

wordle today — July 13, 2022

Excellent article and information, and I will definitely bookmark your site because I always learn something new and amazing when I visit. I appreciate you sharing this with us. wordle today

Tnvelaivaaippu Renewal 2023 — November 12, 2022

Employment is what everyone hopes to get after long years of study and hard work. Students have different plans after school, where some start a business while others opt for employment in the public and private sectors. Tnvelaivaaippu Renewal 2023 In Tamil Nadu state India, the state government has taken the initiative to assist students who have long search for work to no avail. The government has introduced a scheme that caters to unemployed students from backward communities.

teethshare — December 16, 2022

Early findings point to the fact that many political partisans, and especially those who pay close attention to politics slope unblocked, have already factored bias into their assessments.

Anna — February 27, 2023

Yellowstonesjacket is worldwide online store where we offer best & high quality leather jacket including cosplay, jacket made with real leather material. Yellowstones jackets are one of the best brands. We also have a huge collection of Halloween Costumes and jackets offering you in very reasonable price with worldwide free shipping delivery on your door steps!john dutton raw leather jacket

Anna — February 27, 2023

We provide premium full grain leather since it adds to the durability and long life of the garment and is only possible with the best materials and craftsmanship. Consequently, you can choose from a variety of superb leather jackets made of calfskin, goatskin, cowhide, sheepskin and lambskin. Our Website The Designer Jackets is an outstanding selection of leather bombers and biker jackets.

Visit Here:men leather jackets

Idle Breakout — March 1, 2023

Early findings indicate that many political partisans, particularly those who pay close attention to politics,

Kristine — March 5, 2023

Wearing only one-style Abayas might sometimes get boring for you and we completely know that. Hence The Hijab Co. has come up with various Abaya designs to level up your occasional and formal wear, aiming to highlight and draw focus over style with its trendy look! Ensuring to make this one-stop-shop for Abayas online Pakistan

russe lltitus — March 7, 2023

Fashion and styling can be expensive for some people, but at fortune jackets, we aim to keep it as good as possible. Providing quality fashion jackets at reasonable pricing is our motive.

st johns bay leather jacket

connerdalton — March 7, 2023

Looking for premium quality jackets with a wide range of varieties. Well, Right Jackets is the place you wanna be. We deal with jackets of all types. We intend to provide our customers with the most premium quality jackets.

New York Jets Starter Jacket

Terraria — March 15, 2023

Many parts of the world still have not been able to completely end the Covid 19 pandemic.

Melissa — March 15, 2023

Let's fight Covid 19 together and join Terraria to experience the joyful world we humans have created for ourselves.

Abaya — March 24, 2023

Wearing a modest abaya is now so common for every muslim women, most of the abayas is used in Middle east they are likely to wear the modest clothing abaya for there womens. All you have to buy this abaya online in Pakistan.

DiscountCut UK — March 24, 2023

DiscountCut UK offer the brands offers and valid discount deals.

Farooq — April 9, 2023

The best place to get car care items, professional detailing supplies, and car waxes, cleaners, and polishes is at Demnok Online Shop.

Lake Country car detailing accessories

Prime Jacket — April 17, 2023

Good article for Partisanship and the Pandemic. We offer Green Leather Jackets of premium quality at discounted prices. Get it now!

Judah Schmitt — April 21, 2023

One of the great games I've recently been looking for is called cuphead. The game was influenced by the well-known cartoon character of the same name. You should give it a try as well if you have some free time.

edutec.in — May 16, 2023

When I applied for internet banking, I supplied my phone number. However, nothing has changed in my account. My e-banking account was temporarily frozen, and I needed to change my password.Overseas Indian Bank My mobile edutec.in number is being updated, and online banking is enabled on my account. When I applied for internet banking, I supplied my phone number. However, nothing has changed in my account. My e-banking account was temporarily frozen, and I needed to change my password. Overseas Indian Bank My mobile number is being updated, and online banking is enabled on my account.

ebet โปรโมชั่น — June 20, 2023

I want you to know that there is one person who is following your work. ebet โปรโมชั่น

poppy mizzi — July 1, 2023

Thank you for your willingness to share information with us. We shall be eternally grateful for everything you've done here since I know you genuinely care about us. You can play: scribble io to relax, or pass the time!

789betting หวย — August 20, 2023

You are sharing very useful informations. 789betting หวย Its helpful for everyone. Really liked it. Very unique content.

ติดต่อคาสิโนคลิปโต — August 20, 2023

Wow! great blog post! this is interesting I'm glad I've been drop here ติดต่อคาสิโนคลิปโตsuch a very good blog you have I hope u post more! keep posting.

Nova Lemke — September 25, 2023

After reading this amazing and informative post I want to request you to write a blog about pcb assembly manufacturers in china as I am searching for the best post here but I can't find the quality posts.

William — November 27, 2023

Achieve unmatched efficiency with PIM’s dermatology billing services. Our team of seasoned experts and cutting-edge technology make us the ideal choice for your dermatology practice. Minimize claim denials, enhance profitability, and simplify your billing procedures with PIM. With our comprehensive dermatology billing solutions, we ensure you receive rightful compensation for every service rendered.

William — November 27, 2023

Providers can start the enrollment process by visiting the Humana provider portal or contacting Humana directly to obtain the necessary enrollment application forms. At Stars Pro we have an expert Humana credentialing team, our credentialing specialists will enroll you with Humana in minimum time. There are number of Humana credentialing companies in the USA, but our Humana provider enrollment services are highly appreciated by healthcare professionals of the USA.

david roman — December 18, 2023

Hardcore Cycles Inc wasn’t just born overnight. It was nurtured and built by a group of tight knit gear heads with a passion for Brass balls V-Twin. When two people decided to take the chance on an industry with a questionable future.

davidjohn — February 13, 2024

Looking for premium quality jackets with a wide range of varieties. Well, Right Jackets is the place you wanna be. We deal with jackets of all types. We intend to provide our customers with the most premium quality jackets like that cyberpunk jackets. So we make our jackets

Asma khan — March 19, 2024

Wow, these unstitched clothes and fabrics for women in Pakistan are absolutely stunning! The vibrant colors and intricate designs are truly captivating. I've always been fascinated by traditional Pakistani embroidery techniques, and I can't help but wonder if incorporating them into your designs would add an extra layer of cultural richness and beauty. Imagine the fusion of contemporary styles with the timeless elegance of Pakistani patterns—it could create something truly unique and special. Keep up the amazing work! 🌟