Cross-posted at Family Inequality.

You can’t get 18 pages into Hanna Rosin’s blockbuster myth-making machine The End of Men, before you get to this (on page 19):

One of the great crime stories of the last twenty years is the dramatic decline of sexual assault. Rates are so low in parts of the country — for white women especially — that criminologists can’t plot the numbers on a chart. “Women in much of America might as well be living in Sweden,* they’re so safe,” says criminologist Mike Males.

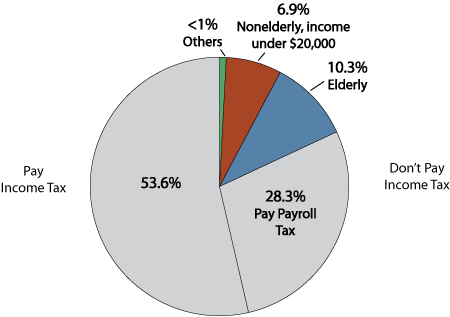

That’s ridiculous, as I’ll show. Rape is difficult to measure, partly because of limiting state definitions, but the numbers are consistent enough from different sources to support the conclusion that reported rape in the United States has become less common in the last several decades — along with violent crime in general. This is good news. Here is the rate of reported “forcible rape” (of women) as defined by the FBI’s crime reporting system, the Uniform Crime Reports.** See the big drop — and also that the rate of decline slowed in the 2000s compared with the 1990s:

(Source: Uniform Crime Reports, 2010)

(Source: Uniform Crime Reports, 2010)

The claim in Rosin’s book — which, like much of the book, is not sourced in the footnotes — is almost too vague to fact-check. What is “much of the country,” and what is a number “so low” that a criminologist “can’t plot” it on a chart? (I’m no criminologist, but I have even plotted negative numbers on a chart.)

Even though she makes things up and her publisher apparently doesn’t care, we must resist the urge to just ignore it. The book is getting a lot of attention, and it’s climbing bestseller lists. Just staying with the FBI database of reported rates, they do report them by state, so we can look for that “much of the country” she’s talking about. I made a map using this handy free tool.

(Source: FBI Uniform Crime Reports, 2010, Table 47)

(Source: FBI Uniform Crime Reports, 2010, Table 47)

The lowest state rate is 11.2 per 100,000 (New Jersey), the highest is 75 (Alaska). You can also get the numbers for 360 metropolitan areas. For these, the average rate of forcible rape reported was 31.5 per 100,000 population. One place, Carson City, Nevada, had a very low rate (just one reported in 2010), but no place else had a rate lower than 5.1. (you can see the full list here). I have no trouble plotting numbers that low. I could even plot numbers as low as those reported by police in Europe, where, according to the European Sourcebook of Crime and Criminal Justice Statistics, for 32 countries in 2007, the median rate was just 5 per 100,000 — which is lower than every U.S. metropolitan area for 2010 (except Carson City, Nevada).

These police reports are under-counts compared with population surveys that ask people whether they have been the victim of a crime, regardless of whether it was reported to police. According to the government’s Crime Victimization Survey (CVS), 65% of rape/sexual assault is not reported. The CVS rate of rape and sexual assault (combined) was 70 per 100,000 in 2010. That does reflect a substantial drop since 2001 (although there was also a significant increase from 2009 to 2010).

And what about the “for white women especially” part of Rosin’s claim? According to the Crime Victimization Survey (Table 9), the white victimization rate is the same as the national average: 70 per 100,000.

I hope it’s true, as Rosin says, that “what makes [this era] stand out is the new power women have to ward off men if they want to.” But it’s hard to see how that cause is served by inventing an end of rape.

—————————

*That is an unintentionally ironic reference, because Sweden actually has very high (for Europe) rate reported rape, which has been attributed to its broad definition and aggressive attempts at prosecution and data collection.

** Believe it or not, this was their definition: “the carnal knowledge of a female forcibly and against her will. Attempts or assaults to commit rape by force or threat of force are also included; however, statutory rape (without force) and other sex offenses are excluded.” That is being changed to include oral and anal penetration, as well as male victims, but data based on those changes aren’t reported yet.

Check the Hanna Rosin tag for other posts in this series.