In early 2011, The Wall Street Journal published “Why Chinese Mothers are Superior” by Yale Law professor Amy Chua in advance of the release of her memoir, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother. Chua’s argument that Eastern parenting is superior to Western parenting (and more likely to produce “successful kids,” “math whizzes,” and “music prodigies”) set off a firestorm of controversy.

In Chua’s view, there’s a simple formula for raising Tiger Kids: place an uncompromising value on education, then reinforce it with hard work, strict discipline, and practice, practice, and more practice. By contrast, she believes Western parents guide their children through positive reinforcement and ask them only to “try their best.”

Chua attributes her successful parenting style to Chinese culture, but failed to acknowledge that she—unlike most parents—has a wealth of resources at her disposal. She and her husband are both law professors at an Ivy League school, and their own parents are highly educated; Chua’s father, for example, is a professor at Berkeley.

Undoubtedly, she and her children have benefited from the intergenerational transmission of advantage. Moreover, Chua overlooks the role of institutions and differences in social and economic capital that give some groups a competitive advantage over others.

Given these glaring omissions, it would be easy to dismiss Chua’s argument as little more than a reification of racial, ethnic, and cultural stereotypes—but by doing so, we’d miss an opportunity to engage in a real discussion. Specifically, how do we explain the academic achievement of Asians, especially when the patterns defy traditional status attainment models?

For example, some second-generation Chinese and Vietnamese have immigrant parents who arrive to the United States with only an elementary school education, no English language skills, and little financial capital, yet graduate as high school valedictorians, gain admission into elite universities, and pursue graduate degrees. Their achievement is vexing; previous research has shown that even when controlling for family background, ethnicity remains significant, and being Chinese, Korean, or Vietnamese gives immigrant children an advantage in educational attainment. But while we know ethnicity matters, we rarely talk about how it matters.

Sociologists have shied away from invoking cultural arguments, worried they might shift the attention from structural inequalities to individual and cultural deficiencies (an either/or argument, instead of a both/and). However, the absence of a strong social science voice in this large-scale discussion has left the door open for scholars like Amy Chua to invoke essentialist cultural arguments (like that of the Tiger Mother) that reach a wide, even international, audience–and resonate.

My aim isn’t to go toe-to-toe with Chua, but to bring ethnicity and culture more analytically into the debate about second-generation educational outcomes. Based on analyses of the Immigrant and Intergenerational Mobility in Metropolitan Los Angeles survey data (IIMMLA) as well as 140 in-depth interviews with 1.5- and second-generation Mexicans, Chinese, and Vietnamese respondents from the IIMMLA survey, I address two main questions.

First, how do 1.5- and second-generation Chinese and Vietnamese exhibit high academic outcomes, even when controlling for socioeconomic factors like parental education, occupation, and income? Second, is there something about being Asian or about Asian culture that confers advantage?

Bridging literature in immigration, culture, and social psychology, I illustrate how ethnicity and culture can operate as a tool kit of resources for some children. More specifically, I explain how immigrant parents and their children frame success, and show how frames are supported by ethnic and institutional resources. These resources cut vertically across class lines, thereby making them available to both middle- and working-class ethnics; this, in turn, helps second-generation Chinese and Vietnamese from poor and working-class backgrounds overcome their disadvantaged class background in their quest to get ahead.

LA’s Chinese, Vietnamese, and Mexicans

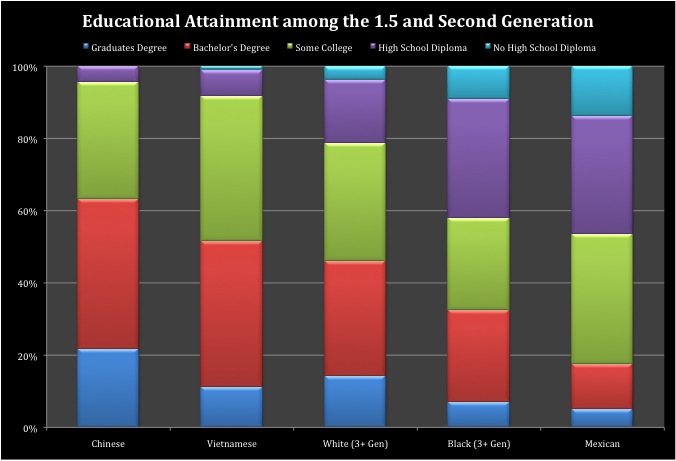

A glance at the IIMMLA survey data reveals distinctive patterns among Chinese, Vietnamese, and Mexicans in Los Angeles:

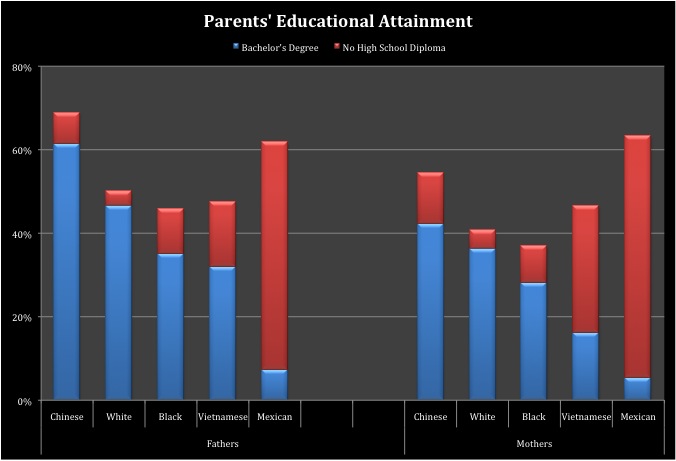

First, Chinese immigrant parents are the most educated of the three groups, reflecting the high selectivity of Chinese immigration to LA. In fact, they exhibit higher levels of educational attainment than both U.S.-born blacks and whites (61% of Chinese immigrant fathers and 42% of Chinese immigrant mothers have a BA or higher).

On the other end of the educational attainment spectrum are Mexican immigrant parents, the majority of whom have not graduated from high school; close to 60% of Mexican immigrant fathers and mothers have less than a high school education. The Vietnamese immigrant parents (especially mothers) fall in between, with lower educational attainment than both native-born whites and blacks.

Turning to their children (the 1.5 and second generation), Chinese Americans exhibit the highest levels of educational attainment, reflecting the intergenerational transmission of advantage of high parental human capital; 64% have graduated from college and, of this group, 22% have also attained graduate degrees. None of the 1.5- and second-generation Chinese students in our study has dropped out of high school.

While Mexicans exhibit the lowest level educational attainment, what often gets lost in presenting cross-sectional, inter-group comparisons is the enormous intergenerational mobility Mexicans have achieved within just one generation. For example, while nearly 60% of Mexican immigrant parents did not graduate from high school, this figure drops to 14% within one generation.

While Mexicans exhibit the lowest level educational attainment, what often gets lost in presenting cross-sectional, inter-group comparisons is the enormous intergenerational mobility Mexicans have achieved within just one generation. For example, while nearly 60% of Mexican immigrant parents did not graduate from high school, this figure drops to 14% within one generation.

Here, the citizenship status of parents is key. On average, children whose parents are undocumented attained two fewer years of education compared to those whose parents migrated legally or those who entered the country as undocumented migrants, but later legalized their status. This two-year difference (11 versus 13 years) is critical in the U.S. educational system, because it divides high school graduates from high school drop-outs.

Furthermore, the college graduation rate among 1.5- and second-generation Mexicans (17%) more than doubles that of their fathers (7%) and triples that of their mothers (5%). When measuring attainment intergenerationally, the children of Mexican immigrants exhibit the greatest mobility of the three groups.

Another notable pattern is the educational attainment of the 1.5- and second-generation Vietnamese, whose educational attainment surpasses both native-born blacks and whites; nearly half (48%) of 1.5- and second-generation Vietnamese has attained a college degree or more, and only 1% has failed to complete high school. Their educational mobility is exceptional given their relatively low parental human capital. While Vietnamese immigrant parents exhibit lower levels of education than native-born blacks and whites, their children’s educational attainment surpasses both native-born groups (moving closer to the Chinese). That poor parental human capital does not obstruct their mobility (as the traditional status attainment model would predict) suggests ethnicity and culture may affect outcomes in ways that immigration researchers have not fully examined.

These vexing results drew me to the literature in culture, and they prompted Min Zhou and me to design a follow-up study of in-depth interviews with 1.5- and second-generation Chinese, Vietnamese, and Mexicans, hoping to understand how they frame—and aim to achieve—success.

Bridging Culture and Immigration—Frames and Ethnic Resources

In the vast literature in culture, I found the concept of frames particularly useful in understanding second-generation outcomes. Following in the footsteps of sociologist Erving Goffman, I define a frame as an analytical tool by which people observe, interpret, and make sense of their social life. Most plainly, frames are ways of understanding how the world works. By untangling the frames people adopt in their decision-making process, we may begin to understand variation in behavior.

Based on in-depth interviews of 1.5- and second-generation Mexicans, Chinese, and Vietnamese, I was able to tease out different frames for “success” and “a good education.” Some frame a “good education” as graduating from high school, attending a local community college, and earning an occupational certificate. Others adopt a frame that involves graduating as the high school valedictorian, gaining admission into an elite university, and going to law or medical school. In other words, it’s not that some groups value education more than others (the essentialist interpretation of culture) but that groups construct remarkably different ideas of what “a good education” means depending on which frames are accessible to them and which they adopt. Ethnicity matters because the frame that members of the 1.5- and second-generation adopt is shaped by the immigrant selectivity (how immigrants differ from non-migrants in their countries of origin), the average socioeconomic status of an ethnic group, and the group’s capacity to mobilize resources.

Because group resources are ethnic resources (they are preferentially available to members of an ethnic group), second-generation ethnics from poor and working-class backgrounds can take advantage of these resources to help override their disadvantage. In this way, ethnic resources can help children whose Chinese and Vietnamese immigrant parents have not graduated from high school, do not speak English, and work in Chinatown’s restaurants and factories compensate for their parents’ low level of human capital and access a group’s ethnic capital instead.

“The Success Frame” — 1.5- and second-generation Chinese and Vietnamese

One of the most striking findings from our interviews was the consistency with which 1.5- and second-generation Chinese and Vietnamese framed “success” and “a good education,” regardless of parental human capital, migration history, and class background. Across the board, these kids told us high school is mandatory, college is an expectation, and only an advanced degree will gain kudos. Caroline, a 35-year-old, second-generation Chinese woman explained:

The idea of graduating from high school for my mother was not a great, congratulatory day. I was happy, but you know what? My mother was very blunt, she said, “This is a good day but it’s not that special.” …She finds it absurd that graduating from high school is made into a big deal because you should graduate high school; everyone should. It’s not necessarily a privilege; it’s an obligation. You must go to high school, and you must finish. It’s a further obligation that you go to college and get a bachelor’s degree. Thereafter, if you get a Ph.D. or a Master’s, that’s the big thing; that’s the icing on the cake with a cherry on top, and that’s what she values.

For people like Caroline, “doing well in school” was narrowly framed as getting straight A’s, graduating as valedictorian or salutatorian, getting into a top UC (University of California school), and pursuing graduate education to work in one of the “four professions”: doctor, lawyer, engineer, or pharmacist. So exacting is the frame that second-generation Chinese and Vietnamese described grades as “A is for average, and B is an Asian fail.” Other respondents were even stricter, explaining that a B is not an Asian fail; an A- is an Asian fail—a sentiment reflected in a recent episode Glee titled, “Asian F.”

Jon Stewart has even jokingly called NBA player Jeremy Lin’s 3.7 GPA at Harvard an “Asian F.”

When we asked Maryann, a 24-year-old, second-generation Vietnamese woman who grew up in the housing projects in downtown LA how she defined success, she relayed, “getting into one of the top schools” (by her account, “UCLA, Berkeley, Yale, Harvard, Princeton, and Stanford”) and then working in one of the “top professions” such as “doctor or lawyer.” When we asked Maryann how she knew the top schools and top professions, she said:

Other parents who have kids. We know a few families who have kids who’ve gone to Yale, and they’re doctors now, and they’re doing really well for themselves.

Maryann’s Vietnamese parents had arrived as refugees to the United States with only a sixth grade education. They do not speak English, they work in Chinatown’s garment factories, and they have raised their family in the projects. In spite of Maryann’s class disadvantage and residential segregation from more privileged immigrants, she recounted a success frame that mirrored that of her middle-class peers.

While Maryann did not graduate from one of the “top schools” she listed, she did graduate from a Cal State university and is now working toward an MA in Education. Despite the extraordinary intergenerational mobility that she has attained, she feels she departed from the success frame (that is, she isn’t really a success) because her GPA was “only” a 3.5 and she attended a Cal State rather than a UC school. Maryann compares herself to her twin sister, who was the high school valedictorian and graduated from Berkeley. Maryann feels she pales in comparison.

Because the 1.5- and second-generation Chinese and Vietnamese turn to high-achieving coethnics as their reference group, those who do not fit the narrow frame for success feel like outliers, and in some cases, failures. But rather than rejecting the constricting frame, they are more likely to reject their ethnic and racial identities, claiming that they do not feel Chinese, Vietnamese, or even Asian because their outcomes differ from “the norm” for Asians.

Ethnic and Class Resources

Simply adopting a frame for academic success can’t ensure a particular outcome; for frames to be effective, they need institutional support and resources. Chinese and Vietnamese immigrant parents support the success frame in a number of ways. First, they buy homes or rent apartments in neighborhoods based on the strength of the public school district. Second, they demand that their children be placed in the Honors or Advanced Placement tracks in high school, and provide supplementary education and tutoring to make sure they get in. Third, Chinese and Vietnamese immigrant parents point to high-achieving coethnic role models to show that the success frame is realistic and attainable. And finally, they acquire information about schools, neighborhoods, and supplementary education programs through ethnic channels. In these ways, ethnicity cuts vertically across class lines and operates as a group resource that’s most beneficial to those with poor parental human capital.

Consider Jason. He’s a 25-year-old, second-generation Chinese who attended elementary school in a working-class neighborhood of Long Beach. As soon as his parents could, they moved to a modest home in Cerritos because they learned from the “Chinese Yellow Book” that Cerritos High School “ranks in the teens.” The Chinese Yellow Book is a 3½” thick, 2,500-page directory that provides a list of the area’s ethnic businesses, as well as the rankings of southern California’s public high schools and the country’s best universities.

When Jason first moved to Cerritos for seventh grade, he was placed in the school’s “regular” academic track. Dismayed, Jason’s parents immediately enrolled him in an after-school Chinese academy. When Jason took the exam for high school, he was placed in the AP track. He graduated in the top 10% of his class and later graduated from UCLA. Now he’s in his third year of law school.

Jason’s parents did not graduate from high school, had little understanding of the American school system, and couldn’t help their son with his schoolwork. But, they were able to rely on ethnic resources to compensate, thereby helping their son attain intergenerational mobility. They weren’t alone in providing supplemental education for their children; supplemental education was such an integral part of the Chinese and Vietnamese students’ adolescence that they hardly characterized it as “supplemental.” For example, Hannah, a 25-year-old, second-generation Vietnamese woman who graduated third in her class with a 4.2 GPA explained that her summers were busy with summer school and tutoring:

Summertime, besides going to summer school every single year, we also did tutoring classes to get ahead. Like in junior high and stuff, we were taking a class ahead, like math classes. If we were going to take geometry, then we were doing it in the summertime, or algebra in the summertime, the summer before. In the Asian community, I think everyone does tutoring.

By taking a class the summer before having to take it during the academic year, students can ensure excellent grades—and a chance to be a step ahead of their peers.

An important caveat is that supplemental education is not unique to second-generation Asian ethnic groups. Sociologists Annette Lareau and Sean Reardon find that higher income families use their class resources to invest more money and time in their children than ever before; this translates into more extracurricular classes, activities, and tutors. However, ethnic resources differ from class resources in that they’re not limited to middle-class and affluent students. The availability of ethnic resources across class lines is what gives second-generation Chinese and Vietnamese from poor and working-class backgrounds a leg up.

Beyond the Tiger Mom

I began this paper by engaging the Tiger Mother controversy in which Amy Chua (and others, including many of the 1.5- and second-generation respondents we interviewed) reduced the educational attainment of high-achieving Asians to the East Asian cultural values. And it’s true: culture matters, but not in the essentialist way that Chua claims. While all second-generation groups in the U.S. value education, groups frame a “good education” and “success” differently depending on immigrant selectivity, the average socioeconomic status of an ethnic group, and the group’s capacity to mobilize resources conducive to upward mobility. Importantly, the success frame is supported by ethnic resources that help compensate for individual family disadvantages.

In this particular frame, academic success becomes the pragmatic goal in itself. Chinese and Vietnamese immigrant parents perceive education as the only sure path to a better life—and this frame fits squarely into the U.S. context in which education is touted as the route to a bright future.

This is not, however, the case in other countries. Among the second-generation in Spain, the Chinese exhibit the lowest educational aspirations and expectations of all second-generation groups, including Ecuadorians, Central Americans, Dominicans, and Moroccans. Nearly 40% of second-generation Chinese expect to complete only basic secondary school—roughly the equivalent of 10th grade in the U.S. Given the perception of a closed opportunity structure in Spain—especially for visible minorities—Chinese immigrants have no faith that a post-secondary education or a university degree will lead to a professional job, so they’ve turned to entrepreneurship and encouraged their children to do the same. Hence, Spain’s Asian immigrants adopt an entirely different success frame, in which entrepreneurship—rather than education—is the mobility strategy. Their frame is supported by ethnic business associations, much like education is supported by a supplementary education system in the United States.

This simple counterfactual illustrates that it’s not something essential about Chinese or Asian culture that promotes exceptional educational outcomes. It also reminds us that what may be most exceptional about “Asian-American exceptionalism” is actually “American exceptionalism.”

Recommended Reading

Annette Lareau and Jessica McCrory Calarco. 2012. “Class, Cultural Capital, and Institutions: The Case of Families and Schools,” in Facing Social Class: How Societal Rank Influences Interaction. An illustrative chapter that shows how middle-class parents are better equipped to navigate the school system on behalf of their children because they can draw on class-specific knowledge and capital.

Mark A. Leach, Frank D. Bean, Susan K. Brown, and Jennifer Van Hook. 2011. “Unauthorized Immigrant Parents: Do Their Migration Histories Limit Their Children’s Education?” Census Brief prepared for Project US 2010: Discover America in a New Century. This report shows the intergenerational consequences of parents’ undocumented status.

Mario L. Small, David J. Harding, and Michèle Lamont. 2010. “Reconsidering Culture and Poverty.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 629: 6-27. An excellent compilation of articles by sociologists who have placed culture at the forefront of the poverty and inequality agenda.

John D. Skrentny. 2008. “Culture and Race/Ethnicity: Bolder, Deeper, and Broader.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 619: 59-77. Shows why it is important to consider immigrants’ countries of origin, rather than just the countries of reception, in studying assimilation.

Jessica Yiu. “Alternative Ambitions: Low Educational Ambitions as a Form of Strategic Adaption among Chinese Youths in Spain.” Papers from the New Second Generation Project in Spain (ILSEG). Princeton: Center for Migration and Development, Princeton University. This study profiles the low educational aspirations and expectations of the second-generation Chinese in Spain—a counterfactual to the essentialist argument that Chinese and East Asians uniformly value education more than other groups.

Comments 22

Robert Moorehead — April 19, 2012

Great article. As a follow-up, the "Asian" values Chua claims for families in Asia seem quite foreign to my university students in Japan. We read excerpts of Chua's work, and students could not relate at all. While my students (at a high-level private university) almost universally attend after-school study programs, aka, cram schools, they reported none of the pressure Chua describes and felt far freer to select their fields of study and to earn lower grades. So, if the particular frames in question are defined as "Asian" frames, and my students are Asian, then something isn't adding up.

Thanks for a great re-framing of the debate.

Letta Page — April 19, 2012

What a good point, Robert! I'm about as caucasian as they come, but some of the "Tiger Mom" messages in this story really hit home; maybe I was a Tiger Kid, too! It's interesting to rethink these parenting styles and expectations as being separate from or operating in conjunction with race, but not being the product of race or ethnicity.

Also, pretty sure I had heard the "BA? That means 'barely average'" before! In North Dakota, are they "Buffalo Moms"?

Lizzie — April 19, 2012

Are potential biological/ genetic differences not even going to get mentioned?

Lizzie — April 20, 2012

Robert, I don't know the answer to your specific questions, (and even if actual scientists don't yet know the answers, that wouldn't mean the answers don't exist.) I think it would be probably useless to argue back and forth on them. But in my opinion your questions don't effectively lay to rest the obvious elephant in the room.

I don't want to be a jerk, and I realize that this is a site that looks at things from a sociological perspective. But I think that any analysis that only looks at environmental/ cultural influences is missing the full picture.

It would be a bit like the biologists saying they can fully perform their analyses by studying DNA, and nope- they need not ever consider the influence of culture and the environment on a complex organism. But they don't do tend to do that. I don't think sociologists should, either.

Robert Moorehead — April 20, 2012

Sociologists, biologists, and other scientists haven't ignored the potential role of biological or genetic factors. Those factors have been studied endlessly, for hundreds of years. And once you get past the pseudo-science of the era of scientific racism, the clear and consistent conclusion has been that there is no concordance between race and other characteristics. Where you or your parents were born does not biologically predispose you to be more or less ambitious or to define success in a particular way.

We have similar groups of people behaving in different ways in different places and at different times. A biological or genetic explanation would have to show that not only are those people somehow biologically/genetically different in some way, but that that difference matters. Many have tried to make this case, but, like a house of cards, their arguments have inevitably fallen apart.

The documentary "Race: The Power of an Illusion" does an excellent job of discussing this very issue, with scholars from many different disciplines. I highly recommend it.

And thanks, by the way, for keeping the conversation civil. That's rare on the internet.

Lizzie — April 20, 2012

Yes, I'm trying to get better about being more civil in discussions! Thanks for noticing!

My impression is that those who wish to throw out the concept of biological race explanations tend to have an ideological interest in doing so. For example, I've heard that in many cultural anthropologists would like to throw out the concept of race. However, I think many forensic anthropologists find race identification a basic aspect of their professional work.

It seems that social scientists prefer social explanations.

A documentary named "Race: The Power of an Illusion" is showing that it has a clear argument to make, based on its title alone. I quickly looked at a synopsis, and it seems it provides a very familiar argument that our ideas about race are but a mirage constructed by history and current politics, etc. One of the big points that gets made a lot is that the lines between the populations are so blurred as to be meaningless. But that can't be the whole story. There are other fields (ie. medicine) where ignoring race is at times considered to be a form of bias.

Maybe issues people have with the term "race" are simply semantic. Let's even say race doesn't exist. Is it possible, though, that somewhat (though not entirely ) isolated gene pools developed sort of independently for thousands of years, and that that created some distinctions among populations?

How could it not? We see it all around in other species, and we see it in our own phenotypes. Why would phenotypes be the only part of us that is a bit unique?

Even in the above example of Chinese folks in Spain, it seems like actually it points to a special quality of the Chinese that they worked out a path to success (entrepreneurship) that actually was more effective than the traditional approach (academics). They seemed to adapt to their environment particularly effectively.

I don't personally think we would ever find a specific gene for "success" or "ambition", (genes are much more complicated than that, right? ) so I think you're defining the question there too narrowly. I agree that differences are not about where you or your parents are from. But I don't agree that research beyond the social sciences has settled the question that differences in populations outcomes are never, in no way related to biology.

Lizzie — April 22, 2012

"Much too young a species for genetics to make any difference?" I don't buy it.

Evolution Can Occur In Less Than 10 Years, Guppy Study Finds

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/06/090610185526.htm

Lizzie — April 23, 2012

Wow- resorting to name calling! Interesting.

tony — April 24, 2012

I'm with Lizzie. Sociologists shut off biology to their peril. It makes them less relevant to intelligent discussion across disciplinary lines. Shouting "social constructionism" is a poor "frame" to rest, to adopt Mz. Lee's terminology.

Genes interact in complicated ways with environmental conditions. It is very plausible that a complex set of genes inclines Asians towards hard work and perseverance, a trait which is most fully expressed in societal contexts in which enable mobility and choice. This says nothing ontologically about the "worth" of Asians -- only that their genetic predispositions are helpful in navigating modern democracies.

Lizzie — April 24, 2012

"Evolution -can- occur in relatively few generations, but only in circumstances of immense competition for resources and genetic bottlenecking (ie, very very small isolated populations)"

-Perhaps the above is exactly what happened?? I think maybe in fact it was one or two major migrations of small founding human populations in Asia?

Also, I'm not exclusively considering "superficial racial indicators". The whole point of the Tiger Kids article is that there are observable differences in Asian populations that are not superficial.

"...given your other comment’s focus on superficial racial indicators as evidence of true genetic diversity, I read a prejudicial root to it. Sounds racist to me."

I think what you meant to write was "as evidence of true genetic similarity" (instead of "true genetic diversity"). Besides calling me an extremely emotionally loaded and offensive term--"racist", you never countered my point, which is that there is probably genetic similarity and uniqueness in Asian populations- even whilst accompanying great diversity as well.

People who actually study this agree:

"Asian populations" have high mtDNA variation with Vietnamese having the highest mtDNA diversity, but, overall, the genetic distance between "Asian populations" is small.

Citation:

Hiroki Oota Takashi Kitano, Feng Jin, Isao Yuasa, Li Wang, Shintaroh Ueda, Naruya Saitou, and Mark Stoneking. (2002). Extreme mtDNA Homogeneity in Continental Asian Populations. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 118:146–153

It is actually very disturbing that you felt it appropriate to label me "racist". Is that generally your idea of an acceptable strategy to shut down an uncomfortable conversation?

I am mainly asking for intellectual honesty here. When the conversation concludes with intentionally dismissive insults, it serves to reinforce my suspicion that this goal is not shared by others.

tony — April 24, 2012

Lizzie,

Unfortunately the spiteful name-calling reflects the condescending tone that many sociologists take when others try to engage them in an intellectual discussion. All too often, sociologists counter with a canned "but everything is socially constructed" response. If the other person pushes back, the sociologist reaches for the next item in their toolkit -- a derogatory name with political baggage (e.g., "racist"). You see it play out here on TSP, but you also find it in the classroom. It's a discouraging state of affairs, but an empirical regularity nonetheless.

Tony

Bob — April 24, 2012

Tony, it's disheartening to read about your many encounters with condescending sociologists - intellectual debates should never end in petty name calling. That said, I am a bit perplexed with your comment about sociologists relying on the notion of social constructions to counter arguments. Are you mentioning this because you feel that sociology's reliance on social scientific terminology to explain social phenomena is itself condescending, or because you feel that it is shortsighted in some way? In either case, how is it any different from a biologist using biology to explain some type of physical phenomena? Or a physicist using physics? Or a chemist using chemistry? In each case, the scholar would likely use theory and terminology specific to his/her own field to explain things. And judging by your response, each scholar's explanation should be viewed as equally condescending and/or shortsighted as the others. So again, I'm not sure why you are singling out sociologists in your response. That is unless your qualms are with sociology as a discipline (as well as the theories and methodologies it utilizes), and less so the people who practice it. That is a different issue altogether, and one I hope could be resolved with a bit of dialogue.

In regards to your accusation about name calling, I am again perplexed. You yourself state that sociologists rely on the notion that "everything is socially constructed" in explaining complex social and natural phenomena. By that logic, a sociologist referring to another individual as being "racist" shouldn't be taken as an attack on that individual's moral character. Rest assured, sociologists understand that, given the socially constructed nature of all human interactions, an individual's manifestation of racist thoughts and actions are simply a reflection of the racist discourses and ideologies present in his/her own environment. So don't fret; people aren't racist. It's just all the institutions that are.

Letta Page — April 25, 2012

You know, it's interesting, but sociologists, geneticists, and biologists have been working together for years. One great article we published when our TSP team was the editorial team for the ASA's Contexts (the public outreach journal of the association) was this one: Beyond Mendel's Ghost. If your library has a subscription, you'll be able to read the entirety here http://ctx.sagepub.com/content/9/4/34.short or here http://contexts.org/articles/fall-2010/beyond-mendels-ghost/

I don't think this is an overlooked overlap at all; it's just that in this case, we're talking about achievement by a certain ethnic or racial group in a specific set of social contexts---essentially, race or ethnicity *can't* explain the broad differences in achievement, so what else can? So we start thinking about the other things that tie these kids: they're immigrants, they're minorities, etc., etc. I think the interplay is really interesting, but biology just wasn't what Jen Lee was bringing to the table---or trying to bring to the table---in this article.

John Lin — April 10, 2013

FYI - Jeremy Lin graduated with a 3.1 at Harvard (i.e. Jon Stewart was incorrect)

2012: Your TSP Favorites » The Editors' Desk — April 1, 2014

[…] Papers: “Tiger Kids and the Success Frame,” by Jennifer […]

The Problem With a Culture of Excellence | Welcome to the Doctor's Office — July 21, 2014

[…] highlight the shortcomings of the cultural essentialist approach, Leewrote in The Society Pages in 2012, “Among the second-generation in Spain, the Chinese exhibit the […]

Myth: East Asians Overvalue Education | Ethnic Muse — July 8, 2017

[…] Lee, J. 2012. Tiger Kids and the Success Frame. The Society Pages. https://thesocietypages.org/papers/tiger-kids-and-the-success-frame/ [accessed: […]