Ten short years ago, same-sex marriage produced deep divisions within American society. The majority of Americans opposed granting legal recognition to gay and lesbian couples, and politicians seemed to play tug-of-war with the issue as it suited their needs. In 2003, Massachusetts became the first state to grant marriage licenses to same-sex couples when its high court ruled that withholding marriage recognition violated the state’s constitution. In the meantime, in his 2004 State of the Union address, President George W. Bush called for an amendment to the federal constitution to block same-sex marriages nationwide. Gavin Newsom, then the mayor of San Francisco, responded a month later by opening marriage to same-sex couples at San Francisco City Hall. It was a short-lived policy, ultimately shut down by the courts, but it drew frenzied media attention; the image of two brides or two grooms tying the knot graced TV screens and newspapers’ front pages, no longer rhetoric, but reality.

By the November 2004 general election, 11 states voted on—and, ultimately, for—ballot measures to amend their state constitutions to ban same-sex marriages. Some even argued that those ballot measures played a decisive role in Bush’s re-election; at a minimum, the initiatives represented a clear right-wing strategy to get socially conservative voters to the polls in a tight election year. In a happy coincidence for the incumbent, those who voted for same-sex marriage bans generally also took the time to vote for the Republican presidential candidate.Now, in 2014, things look quite different. President Obama publicly declared his support for same-sex marriage in the midst of his 2012 re-election campaign, and, less than a year later, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled a section of the federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) unconstitutional. The move opened the door for federal recognition of the same-sex marriages that had been performed in “legal” states. Some Republican strategists now think the issue a “loser” for their party as national polls have started to show majority support for legal same-sex marriage. Although opinion differs dramatically by region, those young and middle-aged, middle-class white voters Republicans could long count on are becoming more liberal on the marriage issue, and political operatives are all too aware that a firm stand against marriage equality might siphon off once-staunch, party line voters.

When an issue seemingly inspired such passion and division just a decade ago, how could it so quickly have become an election day “loser”?

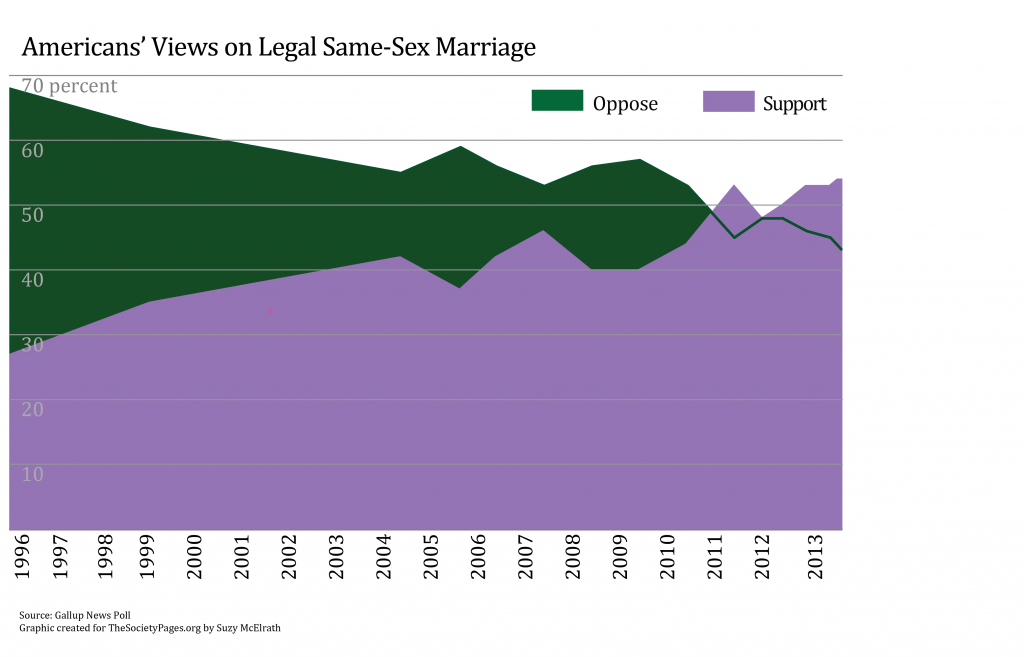

First, a look at the numbers. The figure above shows Gallup poll results on same-sex marriage going back to 1996, the year that Congress passed DOMA. The poll asked: “Do you think marriages between same-sex couples should or should not be recognized by the law as valid, with the same rights as traditional marriages?” Between 1996 and July 2013, the proportion of respondents who said same-sex marriages should be valid rose from 27 to 54%. The proportion saying such marriages should not be valid declined from 68 to 43%. (A small proportion of respondents, never exceeding 5 percent, offered no opinion on the issue.) Other polls, worded differently, have yielded similar results. For example, Pew Research Center asks: “Do you strongly favor, favor, oppose, or strongly oppose allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally?” In 2003, the Pew question yielded 34% in favor and 56% opposed to same-sex marriage; by 2013, 49% of Americans were in favor and 44% opposed. A 2013 Washington Post/ABC News asking, “Do you think it should be legal or illegal for gay and lesbian couples to get married?” showed a 58%-36% divide, with the majority preferring “legal.”

Attitude change that occurs this quickly and on this scale cannot be explained in the usual ways. It’s not a case of older people with more conservative beliefs dying out and being replaced by younger, more liberal generations (what social scientists refer to as a cohort replacement effect). Rather, this kind of rapid shift suggests some individuals are changing their minds on the issue. Indeed, a recent Pew Research Center report noted that more than a quarter of Americans who currently favor legal same-sex marriage stated that they had changed their view on this issue. Historical Pew poll numbers back this up: support for same-sex marriage rose within every age cohort between 2003 and 2013, although age is still a good predictor of views on this issue. For example, support for same-sex marriage among the so-called Silent Generation (those born 1928-1945) rose from only 17% in 2003 to 31% in 2013, while support among Millennials (those born after 1980) increased from 51 to 70%. Acceptance of same-sex marriage is rising at roughly the same rate across generations, but the starting point—those first poll results—is much lower for each previous generation.So, if it’s not just a cohort replacement, what has caused large-scale shift? Several different factors likely contributed. In the March 2013 Pew poll, respondents who said they had changed their minds were also asked why. About a third stated that it had come through knowing someone who was gay, and a quarter attributed the change to getting older, becoming more open, and thinking about the issue more. Smaller proportions cited the prevalence and seeming inevitability of same-sex marriage, the idea that everyone should have freedom of choice without government interference, or a general belief in equal rights.

Beyond these self-reported reasons, at least two other factors have probably contributed to changing views. One is the growing cultural visibility of same-sex relationships and families headed by same-sex couples. Two decades ago, gay and lesbian characters were relatively rare on TV shows and in movies; when comedian Ellen DeGeneres and her sitcom alter ego came out in 1997, it was a major news event. Some TV stations refused to air the coming-out episode of her show. Today, films like Brokeback Mountain can be nominated for Best Picture Oscars and characters like same-sex couple Cam and Mitchell on the TV comedy Modern Family enjoy more plotline attention for their parenting foibles than their sexual orientation. Cultural visibility like this familiarizes people, and for some individuals that increased familiarity is enough to soften opposition to homosexuality and gay rights.

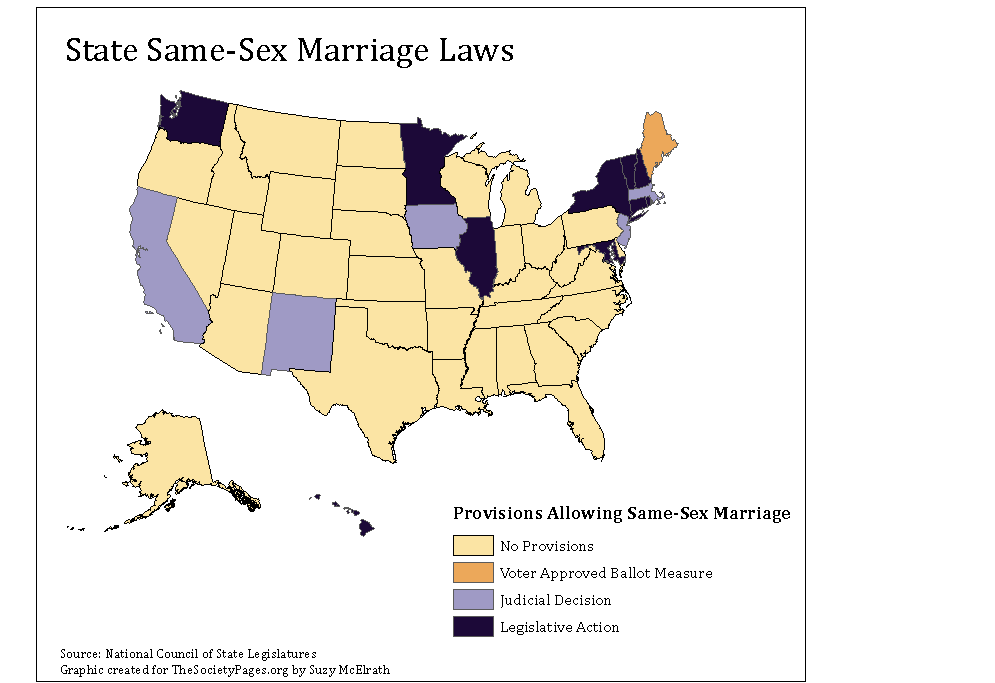

A second factor that has likely contributed to declining opposition to same-sex marriage is the fact that such marriages are now legal in several U.S. states and many countries. At the time of this writing, 17 U.S. states and the District of Columbia (see below), along with 17 countries outside the U.S., recognize same-sex marriage. Not only has the relatively rapid spread of legal same-sex marriage created a sense of inevitability (as noted by some respondents in the 2013 Pew poll), but it also casts doubt on some of the arguments against legal recognition. As more jurisdictions institute legal same-sex marriage and there’s no subsequent clear evidence of harmful outcomes, the direst predictions about marriage equality’s negative effects on “traditional” marriages and children lose credibility.

Changing attitudes about same-sex marriage are occurring in the broader context of changing beliefs about the moral acceptability of homosexuality and other sex-related behaviors. On most of these issues, the general trend has been toward greater acceptance. In Gallup’s annual Values and Beliefs Survey, the proportion of Americans saying that gay and lesbian relations are morally acceptable climbed from 40% in 2001 to 59% in 2013, the largest percentage-point change for any of the twenty issues covered by the survey. (By way of comparison, the proportion saying having a baby outside of marriage was morally acceptable rose from 45 to 60%, and acceptance of sex between an unmarried man and unmarried woman went from 53 to 63%.) Views on the moral status of homosexual conduct almost certainly influence attitudes toward same-sex marriage.

In fact, numerous studies have established that being female, younger, and more highly educated are all associated with greater acceptance of homosexuality and support for same-sex marriage. Those who attend religious services regularly, identify as Republican, and live outside cities generally have less tolerant views. In addition, people who personally know gay men, lesbians, or bisexuals are more accepting; people who believe homosexuality is a choice are less so.In a recent analysis of General Social Survey data from 1988 through 2010, sociologist Dawn Michelle Baunach found that only four characteristics were significant predictors of level of support for same-sex marriage across all survey years: religious attendance, political affiliation, education, and gender. Back in 1988, support for same-sex marriage was mostly limited to highly educated urbanites who were not religious conservatives. By 2010, opposition to same-sex marriage had become localized to older Americans, southerners, African-Americans, evangelical Protestants, and Republicans. Baunach concluded that most of the change in same-sex marriage attitudes was due to a general cultural shift that transcended demographic categories, rather than to changes in the composition of the population or the strength of the influence of certain characteristics on people’s views.

As Americans’ views of same-sex marriage are shifting, opponents and advocates of legal same-sex marriage continually adjust their legal and political strategies. Over the last couple of decades, opponents of same-sex marriage have moved away from strategies that vilify gays and lesbians as immoral and toward arguments emphasizing a concern for children and religious freedoms. This shift was probably motivated in part by the recognition that a declining proportion of Americans had moral objections to homosexuality per se. On the other side, proponents of legal same-sex marriage are shifting away from the language of rights and highlighting the universality of love and equal legal protection of all families. “Post mortem” political research conducted after votes on same-sex ballot measures found the simple message that loving relationships and families of all kinds deserve social support resonated with average voters. Rights-based arguments mostly fell flat.

In ways that may surprise many, the marriage issue has proven controversial even within lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities. Queer critics argue that marriage is a mechanism of social and sexual control, thus antithetical to the founding principles of gay liberation. LGBT feminists express concern that same-sex marriage cannot be disentangled from the patriarchal roots of the institution of marriage itself. Other LGBT skeptics question whether marriage has been the right area of focus for the gay rights movement, given that basic LGBT anti-discrimination protections are still paltry and that marriage may benefit only a small segment of the community (namely, middle-class lesbians and gay men who desire social assimilation). But in interview research that Timothy Ortyl and I conducted with LGBT people in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, we found little support for the idea that same-sex marriage is mainly important to more privileged members of this population. And U.S. Census data on same-sex couples indicate that those couples raising children (who might reap significant practical benefits from access to marriage) are actually disproportionately lower-income people of color, not upper-middle-class whites intent on assimilating into the American nuclear family ideal.

And it’s far from clear that the “traditional” nuclear family holds a prominent place in the American cultural imagination today. The debates over same-sex marriage have unfolded alongside rapid change in Americans’ general beliefs and practices concerning marriage and family formation. With almost half of all first marriages ending in divorce and nearly half of all children being born to unmarried parents, the meanings and practices of marriage and family evolve toward greater diversity. Most Americans still desire marriage, but many no longer view it as essential to a happy life. Further, the ideal of a single marriage as a lifelong commitment bumps up against the realities of longer lifespans and the declining stigma of divorce.

A recent study by sociologist Brian Powell and colleagues affirmed that Americans’ definitions of family were broadening at a rapid pace. Between 2003 and 2006, the proportion who held the most restrictive definitions of family (definitions that generally only included married, heterosexual couples with children) fell from 45 to 38%. Those with the broadest definitions, including same-sex and heterosexual couples with or without children, married or unmarried, rose from 25 to 32%. These are large changes, given the short time period. A follow-up survey in 2010 found a further broadening in definitions of family.

Taken together, the evolution of Americans’ attitudes about same-sex marriage has not one, but several underlying causes. As more gays and lesbians come out to friends and family, more people feel a personal connection to the issue. The passage of time gives people a chance to get used to the idea of same-sex marriage. And with more jurisdictions implementing legal same-sex marriage, some people have come to see its spread as inevitable. Others have noted that the sky has not fallen on those trailblazing states and countries—the consequences some predicted simply haven’t come to pass. True, some of the change is due to cohort replacement, but this accounts for only a small proportion of the overall change. Increasing cultural visibility and declining moral disapproval of homosexuality have real, if difficult to measure effects. Political advocates of same-sex marriage, more effective and research-based, may also account for some of the change. Most broadly, changes in the nature of marriage and family—changes that touch virtually all Americans directly or indirectly—cause many of us to rethink our personal definitions of marriage and family, as well as the purposes and effectiveness of laws and policies that favor some definitions over others.

Recommended Reading

Dawn Michelle Baunach. 2012. “Changing Same-Sex Marriage Attitudes in America from 1988 through 2010.” Public Opinion Quarterly 76(2): 364-378. An analysis of General Social Survey data identifying key predictors of views on same-sex marriage, noting that demographic shifts explain little of the change.

Mary Bernstein and Verta Taylor, editors. 2013. The Marrying Kind? Debating Same-Sex Marriage within the Lesbian and Gay Movement. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. A collection of papers examining debates within LGBT communities on the marriage question.

Andrew Cherlin. 2009. The Marriage-Go-Round: The State of Marriage and Family in America Today. New York: Knopf. An examination of contemporary views and practices related to marriage and family, underlining the high instability in U.S. families resulting from Americans’ contradictory impulses toward marital commitment and individual freedom.

Pew Research Center. 2013. Growing Support for Gay Marriage: Changed Minds and Changing Demographics. Washington, D.C. A summary report of recent attitude trends including acceptance of same-sex marriage, homosexuality, and same-sex parenting.

Brian Powell, Catherine Bolzendahl, Claudia Geist, and Lala Carr Steelman. 2010. Counted Out: Same-Sex Relations and Americans’ Definitions of Family. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. A survey-based exploration of Americans’ evolving definitions of family, identifying trends toward broader definitions.

Comments 3

Friday (what?) Roundup: March 31, 2014 » The Editors' Desk — March 31, 2014

[…] “Same-Sex, Different Attitudes,” by Kathleen Hull. A lot’s changed in just a few years—why are American attitudes on same-sex marriage moving so quickly? […]

Johanna — December 2, 2014

whoah this weblog is great i lobe reading your articles.

Stay up the great work! You know, many individuals are looking around for this info, you can help them greatly.

Kathryn Hansen — June 16, 2017

Excellent article...I am using some of the quoted research findings for a Pride event at my place of work. Thanks for the clear analysis