There have been unusually high levels of movement mobilization since the last presidential election. Within a year of Obama’s landmark 2008 victory, an economic crisis and political backlash sparked a Tea Party movement that dramatically affected the 2010 midterm elections and pulled the entire Republican Party further to the right. The polarizing effect of movements on parties and the tension between ideological purity and securing moderate voters were much in evidence throughout the Republican primaries and continued to haunt the Romney/Ryan campaign in particular.

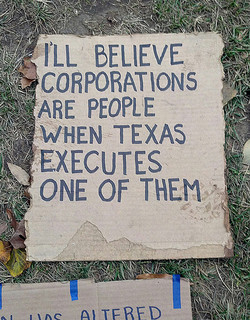

The economic crisis, of course, also sparked another mobilization whose occupation of Zuccotti Park in New York City occurred just over a year ago. Part protest, part demonstration, part carnival, part counterculture, the Occupy Wall Street movement featured an almost impossibly diverse range of issues and constituencies (a prominent poster at Occupy Minneapolis: “I’ll believe corporations are people when Texas executes one”). But at its heart, Occupy challenged the neoliberal narrative, refocused attention on economic inequality, provided a populist counternarrative, and reinvigorated and cultivated progressive voices.

Such activism is a potent reminder that politics in a democracy involves more than just elections. And while the impacts of movements and the outcomes of elections are difficult to predict (and in some cases, assess), sociology provides lasting utility in explaining the social forces that shape movements and their political legacies

Toward A Social Movement Society

Over the last two centuries, social movements have moved from the margins of society to a much more centralized and persistent presence. While the institutionalization of a particular movement can spell the end of effective activism, the broader institutionalization of movements as a form of contentious politics (whereby ordinary people engage in collective action to pursue their interests) has significantly changed our contemporary societal landscape.

The increasing prominence of social movements in societal dynamics is a theme in at least two recent theoretical traditions in sociology. First, consider how the resource mobilization approach uses economic imagery to capture the multiple levels in which movements are embedded.

In this paradigm, movements are defined as preferences for change in a population, but such preferences must be converted into action through social movement organizations. These organizations are, in turn, embedded in larger social movement industries comprised of all the social movement organizations acting on similar preferences for change.

And, above social movement industries, there is an even larger unit of analysis: all the social movement industries in a society comprise the social movement sector of that society. With the concept of a social movement sector, resource mobilization theory asserts that movements have become a permanent, institutionalized presence, coexisting alongside other well-entrenched social institutions. As McCarthy and Zald have put it, particular movements may wax and wane, but the social movement sector and its rich repertoire of contention is now a defining feature of late modern society.In a similar vein, Sidney Tarrow has suggested we are entering a new historical period he calls a movement society. This is the culmination of a two hundred year process. For Tarrow, movements originated in the context of nation-state consolidation. Early challenges to the gathering of state power, however, often had a local, fleeting, temporary character. In the modern era, Tarrow says, “the world may be moving from a logic of alternation between periods of movement and periods of quiescence into a permanent movement society.”

In this society, movements deploy a repertoire of contention diffused through global communication networks to create virtually simultaneous and synchronized protest actions. On a more ominous note, Tarrow implies that globalization may leave transnational movements less subject to state control and that their repertoire and tactics may become more violent. While this assertion is open to dispute, Tarrow’s underlying premise is clear: Social movements are here to stay.

Social Movements and Democratization

The politics of social movements vary widely. Michael Schwartz was one of my mentors in graduate school who claimed that although not all social movements are progressive, all progressive change comes from social movements. There’s an appealing logic here. Why would elites ever accept cuts to their power, privilege, or property unless effectively challenged from below? Moreover, there is abundant evidence that when movements succeed, it’s less by changing attitudes than by raising the costs of “business as usual” to a point where elites are compelled to make concessions they otherwise would not.

Our richest historical analyses broadly support this logic while revealing more subtle nuances in the relationships between social movements and democratization. More than anyone else, sociologist Charles Tilly is an insightful guide through this terrain; he identified at least five reciprocal connections between democracy and social movements.

First, Tilly defined democratic regimes as involving relatively broad and equal citizenship, binding consultation between citizens and governments, and protection of citizens from arbitrary actions by government agents. He regards democracy not as a structure or even a set of institutions but as a process. And this process can move in either direction: democratization or de-democratization. While the broad trend of the last two centuries has been toward democratization, there is nothing inevitable or irreversible about it.

Second, Tilly clarified that, whether you look historically or cross-nationally, you find that the more democratic the government, the greater the range and variety of social movement contention. Thus, with little or no democratization, you get no social movements. With incipient democratization, you get limited protest, but not full-fledged movements. With further democratization, you find actual movements in limited arenas, but they don’t easily spill out into other arenas. And finally, with extensive democratization, there is a widespread availability of movement repertoires that readily diffuse across different arenas and constituencies.

Third, there are some processes, Tilly observes, that act in the background to promote both democratization and social movements. Any demographic, technological, or other social change that increases social networks, equalizes access to resources, insulates public politics from existing inequalities, or proliferates trust networks will facilitate both democratization and social movements.

Fourth, democratization independently promotes social movements by broadening and equalizing rights, increasing binding consultation, and expanding citizen protections. As noted earlier, however, de-democratization can just as easily reverse these gains.

Finally, Tilly finds social movements independently promote democracy when enough democracy already exists to allow them to mobilize popular support, broaden the range of participants, equalize various participants, and at least partially neutralize the effect of categorical inequalities on public politics.

In Tilly’s big picture, then, social movements and democratization reinforce each other in a virtuous cycle. This broad generalization is a good working tool, so long as we remember there’s lots of room for reversals, anomalies, and exceptions to the dominant pattern.

Social Movements and Electoral Contention

Now we can drop down several levels of abstraction to examine the more specific dynamics of political protest and electoral politics. This is the terrain of Frances Fox Piven, whose work reveals the logic of disruptive power as a movement strategy to alter electoral outcomes.

Here’s Piven’s argument: In everyday social life, we are embedded in multiple social networks of cooperation. When we deliberately withhold cooperation, the resulting disruption of those networks creates power for otherwise powerless people. Strikes, boycotts, occupations, and civil disobedience are all examples of such disruptive power in action.

Disruption thus derives its leverage from the breakdown of institutionally regulated cooperation. It occurs when movements violate rules, demand nonnegotiable concessions, or use unconventional or illegal forms of collective action to their advantage.

Piven echoes my mentor Schwartz in saying that most major reforms in American history have been won through the mobilization of disruptive power. At the same time, she acknowledges that using such power is a form of high-risk activism whose occasional gains are often reversed when the disruption inevitably fades away.

But what about elections? In Piven’s view, electoral politics can play an important role in policy formation, but normally electoral politics are dominated by elite interests and inevitably lead to pro-elite policies.

This only changes when people engage in disruptive politics outside the electoral arena. Then disruptive power fractures conventional electoral coalitions and voting blocs within parties. It spurs the defection of some voters and necessitates attempts to gain new ones. In these ways, disruptive power moves electoral politics out of its routine, elite-dominated mold and makes it more responsive to ordinary people and long-neglected needs.

Mass defiance can thus promote progressive policy in two ways. The direct path is when the defiance is substantial enough to constrain elites and their choices, regardless of the electoral cycle. The indirect path is when mass defiance changes the logic of electoral politics, fractures old voting blocs, creates new alliances, and thereby creates opportunities for progressive policy formation.

To summarize, while Tilly paints a historical overview of the intertwined nature of movements and democracy, Piven offers a more specific analysis of how disruptive power can alter the logic of electoral politics and foster more democratic outcomes. But she also sounds a cautionary note about how easily de-democratization can reverse progress in the absence of sustained disruption.

A final piece of scholarship further enriches our understanding of these issues. In a forthcoming book chapter, Doug McAdam and Sidney Tarrow take their own look at the role of movements in electoral contention. Their work bridges Tilly’s broad generalities and Piven’s detailed analysis, starting with the premise that social movements and institutional politics mutually constitute each other in at least five ways.One of the more familiar links occurs when movements make a tactical decision to devote their often-scarce resources to sponsoring parties and candidates in electoral campaigns – the electoral option. Although this may be more effective in systems based on proportional representation than in the winner-take-all districts found in the United States, there has been no shortage of third-party movements in this country. Their success on the national level has been limited, but our decentralized system has permitted more influence for these groups at the state, county, and municipal levels.

A related process is proactive electoral mobilization. Here, electoral campaigns stimulate renewed movement mobilization when people perceive an upcoming election as providing either a threat or an opportunity in relation to their interests. This impulse may lead back to the electoral option or it may lead to a more sustained mobilization that persists beyond the cyclical dynamics of electoral campaigns.

While proactive electoral mobilization begins before an election, reactive electoral mobilization responds to a disputed election with escalating protest. This is more likely in less democratic states, and examples range from Serbia and Zimbabwe to the Philippines and Central Asia. Even the United States, however, saw temporarily heightened protest in response to the highly contested presidential election of 2000 and its dubious resolution by the Supreme Court.

A fourth linkage involves how movements can induce party polarization. The stronger the movement, the more candidates feel compelled to appeal to their base, thereby reinforcing this polarizing effect. This process highlights the tension between the centrist, coalitional logic of elections and the uncompromising, purist ideologies of movements. Parties may be both the beneficiaries and the victims of this polarization as electoral rhythms and governing challenges play themselves out.

A final, and much broader process concerns the links between electoral regimes lasting decades and the corresponding fates of entire families of movements. In the twentieth century, there were three broad electoral regimes involving Republican domination from 1900 to 1932, Democratic domination from 1932 to 1968, and Republican domination once again from 1968 to 2008. In each period, the dominant party significantly influenced the mobilization opportunities of various movements.This last process is especially significant because of its historical sweep and its counterintuitive logic. Common sense might be tempted to say that whichever party is in power will provoke movement challenges from opposing forces, but McAdam and Tarrow claim quite the opposite: “Progressive left movements can be expected to flourish during periods of liberal institutional politics, while the right should be ascendant when conservatives hold institutional power.” Hence, the progressive movements of the 1930s and 1960s thrived under Democratic dominance, while more conservative movements have proliferated during the more recent decades of Republican dominance.

***

Election season has a way of reducing democracy to little more than politicians, polls, and pundits. The scholarship reviewed here reminds us that electoral politics unfold in a much broader socio-historical context. A closer look at that context reveals some surprisingly strong links between social movements, progressive politics, electoral dynamics and the conflicting forces that enhance or diminish democracy.

For example, Piven’s approach illuminates how movements like the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street can shake electoral politics out of their routine, institutional and pro-elite patterns. Tilly’s understanding of democracy as a two-way process highlights the de-democratizing tendencies currently in play, including the Citizens United decision by the Supreme Court, the resulting rise of super-pacs, and various campaigns to restrict or suppress voting rights (to name a few). And, finally, McAdam and Tarrow underscore the potential significance of this particular election and its potential to extend or interrupt what they characterize as a forty-year, Republican-dominated electoral regime with fateful consequences for social movement mobilization.

Long after the politicians and pundits have exhausted themselves (and us) and the polls have proven “wrong,” such sociological insights will endure as more useful tools for understanding the myriad links between movements, elections, and democracy.

Recommended Reading

Doug McAdam and Sidney Tarrow. Forthcoming. “Social Movements and Elections: Toward a Broader Understanding of the Context of Contention.” In Jacquelien van Stekelenburg, Conny Roggeband, and Bert Klandermans (eds), The Changing Dynamics of Contention.

John D. McCarthy and Mayer N. Zald. 1977. “Resource Mobilization and Social Movements: A Partial Theory,” American Journal of Sociology 82: 1212-1241.

Frances Fox Piven. 2006. Challenging Authority: How Ordinary People Change America.

Sidney Tarrow. 1994. Power in Movement: Social Movements, Collective Action and Politics.

Charles Tilly and Lesley J. Wood. 2013. Social Movements: 1768-2012, 3rd edition.

Comments