It’s 5:45 AM in Hong Kong, or so it says on the flight display. We left New York some seven hours ago and most lights are out in the business cabin, but Nicole Santana is working. She is flying business thanks to an upgrade afforded by the thousands of miles accrued flying from New York to China to oversee design and production for OM, a shoe company. On her screen, she is detailing an early prototype shoe that hasn’t come out as she expected. Production needs to widen the strap on the back.

Santana was in the Guangdong Province city to which we are traveling just ten days ago, but she’s returning to make sure production is completed before the Chinese Lunar New Year. The “season” (in fashion time) these shoes are for won’t actually be in stores until nine months from now, but schedule is everything. Production is organized around six collections plus up to three clusters of additional products added in by sales request throughout the year. After a 16-hour flight, Santana will hit the ground running. A local driver will take her straight to OM’s design office to flesh out details with the design managers in one of the factories her company does business with. She will arrive there around 3:30 AM Eastern Time.

Once Santana feels the design is finalized, she will return to NYC. She expects to stay in Guangdong City for five days. After 4 years of working in the company, she has realized that it is better to break what used to be long trips (between two and three weeks) into smaller units. The first trip is ten days, then, a couple of weeks later, she makes a second trip to correct the prototypes she and her team worked on during the first trip. This lets her ensure the samples are made to satisfaction before they’re sent to the U.S. to be shown to buyers and eventually produced and distributed. Santana is in constant contact with two of the factories in China, one factory with its main design office in Miami, and the owners and President of the company, who live on the U.S,’s West Coast. This means that, as she wakes up on our first full day in China, Santana can take advantage of the time differences to check on a project she left in the hands of two associate designers back in New York. It’s 6:00 PM there, and her team has not yet left the office. When she is in New York, Santana regularly comes home from work after 7:00 PM, ready for one last round of emails with detailing and corrections around 10:00 PM, once the China office has opened.In this short description of one senior designer’s schedule, I’ve managed to mention several cities, three time zones, and nine seasons. This is how—and when—fashion production happens.

How Do We Study Cultural Production at the Global Level?

The literature on globalization and culture is currently divided among three primary approaches: macro-level, meso-level, and micro-level. The macro-level perspective, often referred to as the “cultural/media imperialism thesis,” pays close attention to the influence of powerful actors, institutions, and states on powerless actors, institutions, and states (for example, citizens of economically disadvantaged countries). Such approaches find inequalities in cultural exchange, patterns of ownership, and access to infrastructure and technological resources, often concluding that globalization destroys cultural diversity and undermines the vitality of indigenous culture.

A related perspective operates at the meso-level. These studies attend to how city and state bureaucracies organize cultural and economic policy. Authors adopting this perspective emphasize the political economy of globalization in which policy and trade decisions shape local cultural experiences, and provide a window onto the organizational context in which cultural objects are produced and circulated. Similar to macro-perspectives, this literature establishes a “top-down” research strategy that reveals little about the actors who mediate multiple levels of production and reception.

Empirically oriented micro‐phenomenological approaches have recently challenged the cultural imperialism and top-down paradigms. The advantage of this approach is its ability to observe the local dissemination and consumption of cultural goods. This research aims to show the connections between the macro and the micro with a strategy anthropologist George Marcus (1995) has called “follow the thing.” It focuses on the various levels of production, circulation, and use of fashion objects in multiple scenarios. In this paper, I take this third approach, using actual cultural objects—shoes—to demonstrate the round-the-clock schedule of global design and production.

Here it is worth noting that cultural sociologists like myself tend to study designers instead of sweatshop workers as more labor-oriented sociologists (and activists) have rightly emphasized. This alternative focus has three main contributions to make to our understanding of the global production of culture. The first one is that the globalization and commodity chain literature has hidden how intertwined design and production are. Too often this means that all we get to see is that raw materials and supply become a finalized product, in an almost automatic fashion, without an account of all the work it takes to go from one to the other. Secondly, by looking at designers we get to see how all the networks are pulled together in putting together one finalized product, in a way that would be impossible to observe from the end point of a factory worker. Third, the vantage point of the designer allows us to highlight the temporal incongruity of assembling products on a global scale.

Where Does Design Happen?

The production of manufactured goods happens through coordination among many different locales. Scholars who follow every step along the way, studying where the far-flung components come from and how they are assembled until they are finalized, circulated, and consumed, call this a “commodity chain.” The existence of a “global factory” is not a given, but rather the work of many people and institutions that connect different parts of the production and circulation processes. The global supply and production chains are contingent on many people and require flexibility, cooperation, and speed. Executive fiat or managerial omniscience have little to do with getting a fashion designer’s sketch to the runway.

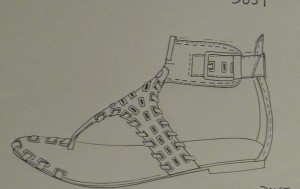

In fact, it’s sometimes hard to pinpoint where and when design happens. Does it start when designers assemble drawings and inspiration boards in their offices, hoping to make sense of how they work as a collection? Maybe it’s earlier, when designers are traveling to Europe and a few major shopping districts in the U.S. (mostly in Los Angeles, New York, and Miami) to look for inspiration in shoes, belts, buckles, and accessories. Or even before that, when scouting the very expensive online trend forecasting service companies like OM pay for the latest pictures of Milan’s runway shows, the window displays of Paris’s trendy Le Marais neighborhood, or a heavily stylized woman’s “street fashion” in Yokohama, Japan?

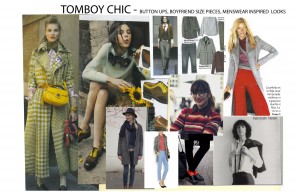

When designers synthesize all that “global” information, they create mood boards, they are putting together a storyline about the colors and materials they will use to imagine their potential customers. Are they neo-romantics? Tomboy chic? The drawing process will help those “moods” and each shoe intersect. Designers must also take into account which shoes will replace those from previous collections. Is there a sandal for the West Coast buyers? What about a “crazy” or conceptual shoe that a couture lover could take from the runway to a gala? In all of this process, regardless of whether the conversation is sited within is a shopping trip to Berlin, an image from a Sao Paulo street, or a physical meeting in the Pacific Northwest, the same people discuss information and trend reports; imagine how the many buckles, shoes, watches, swatches that they bought can become shoes; correct drawings; discard up to 70% of the designers’ initial work (for a final collection of 35 shoes, designers draw up more than 100).

Where Does Production Happen?

Production is constant. It happens simultaneously in many places. The beginning of the chain I followed starts at company headquarters on the West Coast and in New York, where most of the design team works (in fact, where most design teams work—including those of French Connection, Kenneth Cole, Coach, BCBG MAZARIA, Sam Edelman, Frye, and Steve Madden). It’s no mistake that designers cluster together: they need to socialize and brainstorm with other designers, there must be good schools that provide companies with an influx of young talent (in New York, the Parsons School of Design is queen, but SUNY’s Fashion Institute of Technology and even Pratt send talented graduates into companies like OM), and there have to be shared services and expert knowledge that can circulate among the firms that make up the fashion ecology.

The first production decision the CEO and the head designers make is how many collections there will be in a year (lately, from 4 up to 9 a year, though the timing between collections is blurred by a now-constant design process demanded by the fast fashion market). Then they decide how many lines will there be per collection and which are the consumers they are designing for. In deciding this, the firm is also choosing which companies will provide for shoe’s components (the leather, insoles, and accessories, for example) and which sample rooms and factories will build the prototypes (first versions of the shoe, usually done with discarded materials and scraps), the sale samples (the one OM uses to gauge interest from potential buyers in seasonal fashion shows), and the confirmed samples for quality and design. In 2013, OM made 2.5 million pairs of shoes, all of which emerged from these many minute decisions.The factories (in this case in China, India, and Mexico) also compete to participate in this production process. They do so via agents, who coordinate the match between shoe-company and factory by offering to produce samples, thus showing off the quality of the shoes they make. The factories are specialized and only produce shoes. OM’s factories are located in three places: Mexico’s Leon, where the men’s collection is produced, to take advantage of the local craft industry’s talent with leather products and the favorable exchange rate; in Chennai, India, where the cheapest line, made of leather and less noble materials like plastic Is developed; and in Guangdong Province, where most of the volume of production (for both OM, the “diffusion line,” and OMA!, the company’s high-end line) takes place. As much as this all happens globally, there is local competition. In China, northern provinces such as Saaxchi compete against the Special Economic zones in Guangdong and Fujian. Even within Guangdong, cities like Shenzhen, Dongguan, and Guangzhou compete to become the province’s center of shoe production.

Now, what does production look like to the designer? While I’ve been able to map all the macro components of how a shoe is produced, the day-to-day work of putting the shoe together is a little bit messier. Let’s follow one shoe to see how it works.

A drawing with instructions and a second file, including a sample request in an excel sheet with precise descriptions of the pattern, binding, laces, studs, eyelets, zipper puller, button buckles, zippers, and upper stitching, as well as the lining, with its insole binding, sock, sock stamp, heel, welt, outsole, etc., are sent to one of OM’s factories in Dongguan.

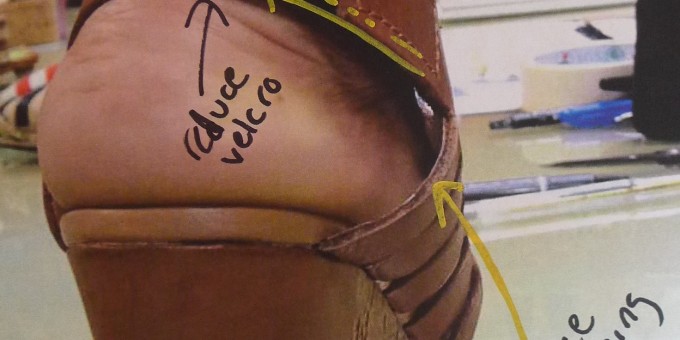

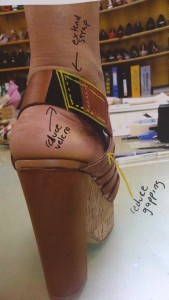

Once that first shoe gets developed into a prototype, Nicole Santana receives an email with a picture and detailed information, along with a picture of the shoe on the foot model in the sample room. After close scrutiny, Nicole draws corrections onto the images. Now the main factory in China must triangulate that information with a development company in Miami that partially owns the factory. Corrections may last several rounds of design and material issue changes, but shoes do not go into production until the sample is confirmed.

As shoes get closer to confirmed samples, Santana and her team will again travel to Guangdong Province for the final phase of development. Daily meetings with the sample room managers of the three factories will happen in factory offices (neatly tucked out of sight), in the sample room, and in OM’s office in China, Monday through Saturday, from 9am to 10pm. Santana supervises production and repeats the process she did over email, but in person, looking at the shoes on a model, then trying them on herself to see how it fits on a “U.S.” leg like hers. Once she gets a “feel” for how well the parts fit, she redraws on an actual shoe developed with the actual materials. The shoe will be resampled in the next 48 to 72 hours.

Again, some 30 to 40% of shoes that make it to sample will be dropped because they’re not coming out as imagined. The others will be corrected yet again as Santana returns to the U.S. While keeping one foot, so to speak, in China, Santana starts the same process for the next collection and the factories finalize the samples. The final touches, down to the proper insole stitching, will require one more trip to the sample room—or five to six days of travel for Santana. Once the samples are given the “okay” and rushed into production, samples are carried back to the United States. If a pair is hand-carried, it’s usually with a hole drilled into one of the soles to prove to U.S. Customs agents that the shoes aren’t being carried for resale.

Why Are Shoes Made in China?

China’s economic reforms since the ‘80s and the deindustrialization of Western countries have, of course, been the main engines behind the country’s production boom, but history also plays a role. Many of the factories working with U.S. shoe production companies are owned by Taiwanese families; they owned factories in Taiwan in the 1970s (when “Made in Taiwan” was in every garment you could get your hands on) and, later, the South Korean factories fueling the early round globalized sneaker production. As production costs lowered in China, the Taiwanese entrepreneurs invested in Dongguan. Thus, it’s not unusual, while in Guangdong Province, to meet with agents, quality control officers, and technicians who are all of Taiwanese origin. Sample room managers, on the other hand, are Chinese: they need to be able to communicate with the local workers.

In many popular accounts of globalization, the world appears frictionless or flat. The idea is that production is always ready to be moved into any country or area that makes itself cheaply available. But previous infrastructure and knowledge matter. As I’ve observed Taiwanese factory owners (and their cadres of experts) producing shoes for decades and making careful choices about where to do so, so, too, are global pharmaceutical companies developing high cost drugs particular about where they conduct medical experiments. These medical trials tend to happen in Eastern European countries like Poland, or in technocratic Brazil, where there is a system of physicians in place that can centralize the supply of patients to might need the medicine, appropriate medical facilities, and certified doctors.

This changeability of geography is both a hallmark of globalized production and a symbol of how flexible and responsive supply chains have become. For instance, a look at the production of other low technology and labor-intensive industries, like garment or furniture production, shows what sociologists have called “a virtuous cycle” of production. Spanish Apparel company Zara, given the nature of fast fashion, does not bring in products from Southeast Asia like its competitors; what they save in transportation costs, they can spend in salary and technology. As competing countries like Portugal, Morocco, and Turkey improve their technology, Zara changes the locations of its main suppliers.

A similar process can be observed in countries that started out producing low-tech, labor-intensive products like t-shirts. As local salaries grew, entrepreneurs divested their money by either shifting into more refined clothing, or, as working condition improved and unions formed, into low-end electronics assembly. Something like this is happening in Dongguan. Lately, it’s become too expensive for international production; some capitalists are starting to invest in electronics instead of shoes. Those who stick with shoes are moving into China’s Northern Provinces, where salaries and production costs are lower.

Where Do Supplies Come From?

Of course a shoe needs to be made out of something—or some things. There is great variation in terms of where in the world parts come from. OM hires an Italian agent from Milan to coordinate the global materials and make sure they get to the design companies. Most of the higher quality shoes are built with leather from the two tanneries the Italian company owns in Tuscany. Other higher-price-point shoes are made from leather sourced in south Brazil (from Franca, in São Paulo State, and Novo Hamburgo, in Rio Grande do Sul Province). For OM’s other shoes, leathers are sourced from Chengdu, in Sichuan Province, or from India (Chennai) and Thailand (though the carcasses processed in Thailand’s Samut Prakan province actually come from the Buenos Aires metropolitan region in Argentina). So it is that one Italian leather supply agency descrambles a global network of suppliers and producers, sometimes by linking OM directly with suppliers that fully finalized the leather on their own; sometimes by supplying carcasses to tanneries; sometimes by working and reworking lower quality leathers in their own tanneries; and sometimes simply supplying their own Italian product.

When Does Design and Production Happen?

Put simply, design happens all the time. It’s a 24-hour cycle that includes both email and live presence. If a shoe is first drawn in New York, there is a constant exchange of emails with headquarters in the West (in the Pacific time zone) and with OM’s China office. Santana’s team works to consider pricing and consumer constraints that should take a shoe off their list. For those shoes that will move forward, they must gather an immediate analysis of whether the factories in China can produce such a shoe and whether the materials are available. This means that, if a day started when Santana woke up in New York, went to the office, and checked the emails that came in from Dongguan, that day never actually ended. Santana’s first morning email answers queries and concerns about scheduling and capabilities in China. Later, as she arrives at her office, her team works to make sense of the constraints and developments signaled by the China office. Past noon, they contact the West Coast with updates on the designs. Essentially, communication subsumes Santana’s entire day. Before going to bed, she will spend another hour furiously emailing as South China wakes up and begins its workday.

This 24-7 dynamic has affected many industries. Take, for example, architecture, with firms in Europe and the U.S. shifting work schedules when developing projects in Southeast Asia to make themselves available to the clients and local builders in real time. So if one week an architectural team is working on a U.S. project and operates from 10am to 7pm, its timing shifts to develop a residential complex in Istanbul (with those workers committed to the project arriving earlier than the rest of the team), and it absolutely changes if the client is a mall in Hong Kong—for that, teams will arrive at the office at 7pm, ready for an all-nighter. Nevertheless, no industry has been more affected by the restructuring of time than financial services, with firms in London literally making time into money, since their time zone gives a competitive advantage, allowing them to be open—albeit briefly—at the same time as the Tokyo and New York Stock Exchange services and banks.The cycle of production in the fashion industry has actually intensified lately. The influx of “fast fashion companies” (like Zara, Forever 21, H&M, and Topshop) has destroyed the old-fashioned cycle of four “seasons” with intermittent mini-collections. Now, if a piece has gone down a high fashion runway anywhere in the world, the inexpensive (or less expensive) version of it is expected in stores within weeks. OM now has nine annual collections. A second development that affects the temporality of production is that most work is now done in terms of projects rather than work days. There’s little concern for an established work week or work hours, predictable vacation days, and the combination of work and leisure people expect in a highly skilled occupation like clothing designer. This is true in similar industries like architecture, media, and advertising. The most tragic exemplar is the recent death of a copywriter in a Singapore ad agency: he died after working for three days straight. There just wasn’t time for sleep.

***

A shoe is a great conduit to see the global dynamics at play in the production of an economic good. And while these dynamics are easier to understand with products that need intensive technology and transform raw materials into a final product, globalization is also affecting “natural,” unprocessed items like fruits and vegetables, as well as immaterial products, like pharmaceutical or medical expertise. To close, I want to call attention to something Americans consume as readily as shoes: sushi.

High quality tuna, the kind that is served in expensive restaurants in New York, London, or Paris, is brought in from the main market in Tokyo, Tsukiji, while actually fished in the North Atlantic, either on the shores of New England and Halifax or near the Straits of Gibraltar (the highly migratory tuna is sold to middlemen who send the highest quality fish to Tokyo). Time zone differences play a crucial role in the circulation of this fish, since buyers (mostly Japanese) call the Tsukiji market, in which the auction has just concluded, and jumbo jets and high-tech refrigeration ensure fresh fish is sent around the world daily. Fish from South Spain, where it is actually trapped, put into a pen, and fed, also makes it to Tokyo, where its “global” value will be set by expert buyers (much like the fashion buyers who can distinguish among different qualities of leather, these fish experts can distinguish among qualities of fish). Industrial fishing happens in coordination with the demand of the Tokyo market, so much that it affects local production and consumption elsewhere. Sometimes tuna is fished to replace good stock that is being exported to Japan; some Spanish tuna ends up in U.S. supermarkets, replacing the American tuna that was exported to Japan; and in some cases, U.S. tuna comes back from Japan, certified by quick circulation through the Tsukiji marketplace.

Whether it’s fish or fashion, globalization is happening everywhere, all the time.

Recommended Readings:

Sidney Mintz. 1986. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. New York: Penguin. Traces the history of sugar production and consumption, showing its links to slavery, class ambition, and industrialization.

Theodor Bestor. 2001. “Supply-Side Sushi: Commodity, Market, and the Global City,” American Anthropologist 103 (1): 76-95. Describes how Tokyo’s Tsukiji market mediates multiple, worldwide locations, culinary fashions, and the fish industry to produce sushi at a global scale.

Adriana Petrina. 2009. When Experiments Travel: Clinical Trials and the Global Search for Human Subjects. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Brings together the players in clinical trials, from corporate laboratories in the U.S. to research and public health sites in Poland or Brazil to show how commercial medical science is integrated into local health systems.

Xuefi Ren. 2011. Building Globalization: Transnational Architecture and Production in Urban China. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Shows the many ways urbanization and globalization are intertwined in China by studying transnational architectural production in aspiring global cities like Beijing and Shangai.

Pietra Rivoli. 2009. The Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy: An Economist Examines the Markets, Power, and Politics of World Trade, 2nd Edition. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publishers. Following a T-shirt she bought for the holidays, the author untangles the history of the globalization of world trade, specifically in the textile industry.

Comments