Collectively, Americans have a particular idea of what constitutes genocide. Notions of the Holocaust, Cambodia, or Rwanda are generally what come to mind. Almost universally they have two things in common; they are tied to events that happen abroad, and they involve killing on a massive scale. This clear notion of what constitutes genocide can be traced back to the legal definition of genocide, found in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

Raphael Lemkin

One hundred years ago this month, facing defeat and pressure from the Allied powers than won WW I, the Ottomans began attributing blame for the massacre of its Armenian and Greek citizens. Putting the Three Pashas (Talat, Enver & Djemal) on trial with other leaders of the Committee of Union and Progress, the Turkish Military Tribunals found the defendants guilty and sentenced to death. However, , the Pashas were able to flee Turkey and escape punishment (for some time, at least). The allies, frustrated by the perceived ineffectualness of the Turkish courts, in turn established the Malta Court to prosecute war criminals. By 1922, though, the Turkish defendants were repatriated to Turkey, largely due to the absence of a legal framework for prosecution. The lack of justice from the international community would spur a young Raphael Lemkin toward a lifelong goal of pursuing legal safeguards to prevent massacres like those of the Armenians from reoccurring.

One hundred years ago this month, facing defeat and pressure from the Allied powers than won WW I, the Ottomans began attributing blame for the massacre of its Armenian and Greek citizens. Putting the Three Pashas (Talat, Enver & Djemal) on trial with other leaders of the Committee of Union and Progress, the Turkish Military Tribunals found the defendants guilty and sentenced to death. However, , the Pashas were able to flee Turkey and escape punishment (for some time, at least). The allies, frustrated by the perceived ineffectualness of the Turkish courts, in turn established the Malta Court to prosecute war criminals. By 1922, though, the Turkish defendants were repatriated to Turkey, largely due to the absence of a legal framework for prosecution. The lack of justice from the international community would spur a young Raphael Lemkin toward a lifelong goal of pursuing legal safeguards to prevent massacres like those of the Armenians from reoccurring.

December 9th is the International Day of Commemoration and Dignity of the Victims of the Crime of Genocide. It commemorates the adoption by the United Nations of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in 1948. On this 68th Anniversary of the Genocide Convention, it is a stark reminder that the world still lags behind the ambitious goals envisaged by not only Raphael Lemkin but also the signatories to the convention. Over the past few months, the United Nation’s Office of the Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide has issued warnings on the current state of affairs in South Sudan, Aleppo, Syria and Northern Rakhine State, Myanmar. In a rather ironic twist, we have grown accustomed to debating whether a conflict is a genocide or not, rather than working together to stop genocides from unfolding. Despite clear and early warnings about the possibility of a genocide unfolding, there is still a yawning gap between how events unfold, and our response to ending/curbing human suffering due to conflict.

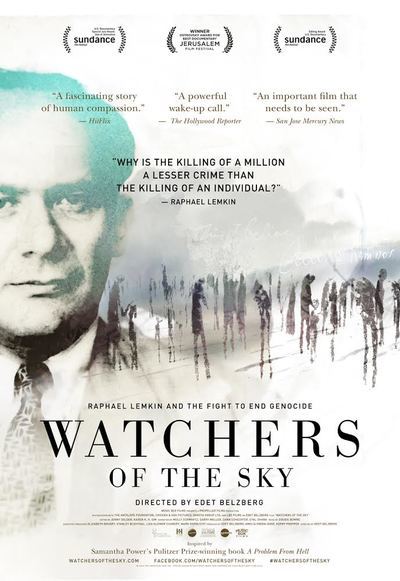

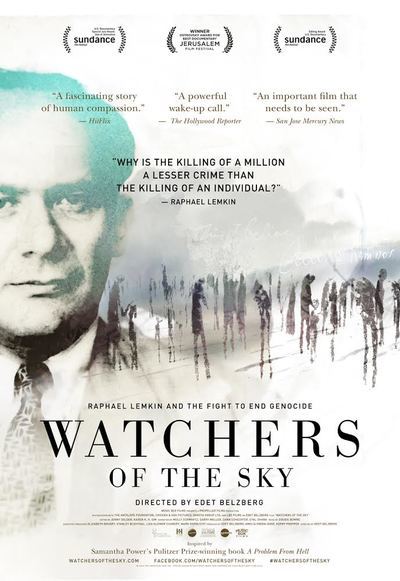

Six decades after he first coined the term genocide, Raphael Lemkin’s life has made it to the silver screen. In Watchers of the Sky director Edet Belzberg takes viewers through the efforts of Lemkin to get the crime of genocide recognized by the international community and the United Nations.

Six decades after he first coined the term genocide, Raphael Lemkin’s life has made it to the silver screen. In Watchers of the Sky director Edet Belzberg takes viewers through the efforts of Lemkin to get the crime of genocide recognized by the international community and the United Nations.

Throughout the movie, activists, scholars and experts share their reflections on the legacy of Lemkin’s tireless dedication to pursuing justice for victims of atrocities around the world. Among those interviewed is Samantha Power, U.S. Ambassador to the UN and author of A Problem from Hell, which served as an inspiration for the documentary. more...

“We are in the presence of a crime without a name,” said British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in 1941, in a radio broadcast in which he described the barbarity of the German occupation of the Soviet Union.

Only a few years later, thanks to the determined and tireless efforts of the Polish Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin, this type of atrocity the destruction of entire human groups would have a name and be declared a crime under international law in a treaty that is binding on all states that ratify it: the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. While it was too late to save the Jews of Europe, there was a lesson to be learned from the widespread passivity in the face of the Nazi mass killings. As Raphael Lemkin wrote in the postwar years, “by declaring genocide a crime under international law and by making it a problem of international concern, the right of intervention on behalf of minorities slated for destruction has been established.”

December 9 marked the 64th anniversary of the UN’s adoption of the Genocide Convention, which has come to embody a milestone in the history of human rights and the promise of a world free of this odious crime.

We know that this promise, symbolized by the words “Never again,” has not been fulfilled. Still, the Genocide Convention laid vital foundations and has borne significant fruit.

Sixty-four years down the line, mass atrocities cannot be universally ignored. More states have signed the Convention, fewer states believe that sovereignty is a license to kill, many perpetrators have been held accountable for their crimes, and, above all, the international community has shown that it can take collective action to prevent and punish genocide.

Best wishes for a peaceful new year.

Alejandro Baer is the Stephen Feinstein Chair and Director of the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. He joined the University of Minnesota in 2012 and is an Associate Professor of Sociology.

One hundred years ago this month, facing defeat and pressure from the Allied powers than won WW I, the Ottomans began attributing blame for the massacre of its Armenian and Greek citizens. Putting the Three Pashas (Talat, Enver & Djemal) on trial with other leaders of the Committee of Union and Progress, the Turkish Military Tribunals found the defendants guilty and sentenced to death. However, , the Pashas were able to flee Turkey and escape punishment (for some time, at least). The allies, frustrated by the perceived ineffectualness of the Turkish courts, in turn established the Malta Court to prosecute war criminals. By 1922, though, the Turkish defendants were repatriated to Turkey, largely due to the absence of a legal framework for prosecution. The lack of justice from the international community would spur a young Raphael Lemkin toward a lifelong goal of pursuing legal safeguards to prevent massacres like those of the Armenians from reoccurring.

One hundred years ago this month, facing defeat and pressure from the Allied powers than won WW I, the Ottomans began attributing blame for the massacre of its Armenian and Greek citizens. Putting the Three Pashas (Talat, Enver & Djemal) on trial with other leaders of the Committee of Union and Progress, the Turkish Military Tribunals found the defendants guilty and sentenced to death. However, , the Pashas were able to flee Turkey and escape punishment (for some time, at least). The allies, frustrated by the perceived ineffectualness of the Turkish courts, in turn established the Malta Court to prosecute war criminals. By 1922, though, the Turkish defendants were repatriated to Turkey, largely due to the absence of a legal framework for prosecution. The lack of justice from the international community would spur a young Raphael Lemkin toward a lifelong goal of pursuing legal safeguards to prevent massacres like those of the Armenians from reoccurring.

December 9th is the International Day of Commemoration and Dignity of the Victims of the Crime of Genocide. It commemorates the adoption by the United Nations of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in 1948. On this 68th Anniversary of the Genocide Convention, it is a stark reminder that the world still lags behind the ambitious goals envisaged by not only Raphael Lemkin but also the signatories to the convention. Over the past few months, the United Nation’s Office of the Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide has issued warnings on the current state of affairs in South Sudan, Aleppo, Syria and Northern Rakhine State, Myanmar. In a rather ironic twist, we have grown accustomed to debating whether a conflict is a genocide or not, rather than working together to stop genocides from unfolding. Despite clear and early warnings about the possibility of a genocide unfolding, there is still a yawning gap between how events unfold, and our response to ending/curbing human suffering due to conflict.

Six decades after he first coined the term genocide, Raphael Lemkin’s life has made it to the silver screen. In Watchers of the Sky director Edet Belzberg takes viewers through the efforts of Lemkin to get the crime of genocide recognized by the international community and the United Nations.

Six decades after he first coined the term genocide, Raphael Lemkin’s life has made it to the silver screen. In Watchers of the Sky director Edet Belzberg takes viewers through the efforts of Lemkin to get the crime of genocide recognized by the international community and the United Nations.

Throughout the movie, activists, scholars and experts share their reflections on the legacy of Lemkin’s tireless dedication to pursuing justice for victims of atrocities around the world. Among those interviewed is Samantha Power, U.S. Ambassador to the UN and author of A Problem from Hell, which served as an inspiration for the documentary. more...

“We are in the presence of a crime without a name,” said British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in 1941, in a radio broadcast in which he described the barbarity of the German occupation of the Soviet Union.

Only a few years later, thanks to the determined and tireless efforts of the Polish Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin, this type of atrocity the destruction of entire human groups would have a name and be declared a crime under international law in a treaty that is binding on all states that ratify it: the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. While it was too late to save the Jews of Europe, there was a lesson to be learned from the widespread passivity in the face of the Nazi mass killings. As Raphael Lemkin wrote in the postwar years, “by declaring genocide a crime under international law and by making it a problem of international concern, the right of intervention on behalf of minorities slated for destruction has been established.”

December 9 marked the 64th anniversary of the UN’s adoption of the Genocide Convention, which has come to embody a milestone in the history of human rights and the promise of a world free of this odious crime.

We know that this promise, symbolized by the words “Never again,” has not been fulfilled. Still, the Genocide Convention laid vital foundations and has borne significant fruit.

Sixty-four years down the line, mass atrocities cannot be universally ignored. More states have signed the Convention, fewer states believe that sovereignty is a license to kill, many perpetrators have been held accountable for their crimes, and, above all, the international community has shown that it can take collective action to prevent and punish genocide.

Best wishes for a peaceful new year.

Alejandro Baer is the Stephen Feinstein Chair and Director of the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. He joined the University of Minnesota in 2012 and is an Associate Professor of Sociology.