Early this week Frank Navarro, a United States Holocaust Memorial Museum trained teacher who has taught at Mountain View High School in California for 40 years, was put on leave after a parent complained about the parallels he was drawing in his world studies class. He was accused of comparing Trump to Hitler, but in actuality he had only pointed out the connections between Trump’s presidential campaign and Hitler’s rise to power.

On September 1 of this year, Holocaust scholar Michael Berenbaum wrote in the article With gratitude toward Donald Trump, how as an educator, he was grateful to Trump for making it easier for him to explain to his students, how it was possible for the Nazis and Hitler to come to power. In my own classroom, it is my students who have made the connections, as I certainly did not have to spell it out for them. We all agree that Trump is not Hitler, but certainly the rhetoric and unabashed racism, antisemitism and xenophobia unleashed by his campaign reminds us of the tactics used by Hitler, the Nazis and his followers.

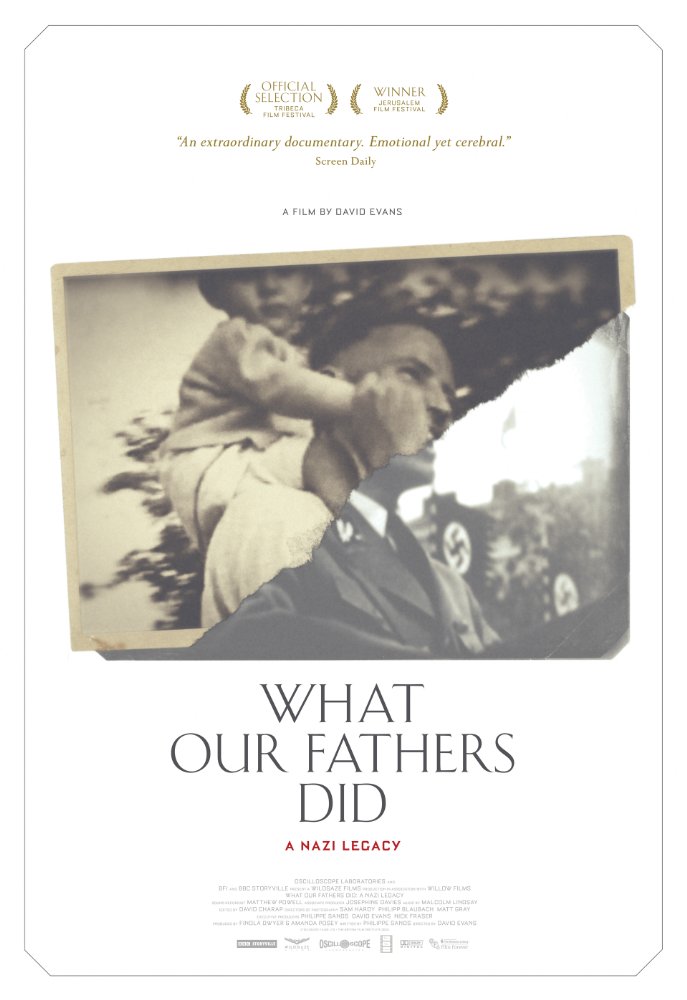

What Our Fathers Did: A Nazi Legacy

What Our Fathers Did: A Nazi Legacy Elie Wiesel had a profound effect on my life. In 1997 I embarked on a journey to earn my Master’s degree from the University of Minnesota. At the time that I began my classes I had no thoughts of studying the Holocaust, but through a series of small events, I found myself thinking of nothing else. I do not remember when I read Night, nor do I recall what led me to return to Wiesel’s work while in graduate school. For some reason I turned to a little known collection of his short stories titled One Generation After, published in 1970. How the book found its way from my mother’s bookshelf to mine is not clear, but for some reason, I picked it up and read it. The story that changed my life was “The Watch.” Over the course of six pages, Wiesel tells of his return to his home of Sighet, Romania and the clandestine mission he undertakes to recover the watch given to him by his parents on the eve of his Bar Mitzvah. It is the last gift he received prior to being transported with his family to Auschwitz. Like many Jewish families, fearing the unknown and hoping for an eventual return, he buried it in the backyard of their home. Miraculously, he finds it, and quickly begins to dream of bringing it back to life. However, in the end he decides to put it back in its resting place. He hopes that some future child will dig it up and realize that once Jewish children had lived and sadly been robbed of their lives there. For Wiesel the town is no longer another town, it is the face of that watch.

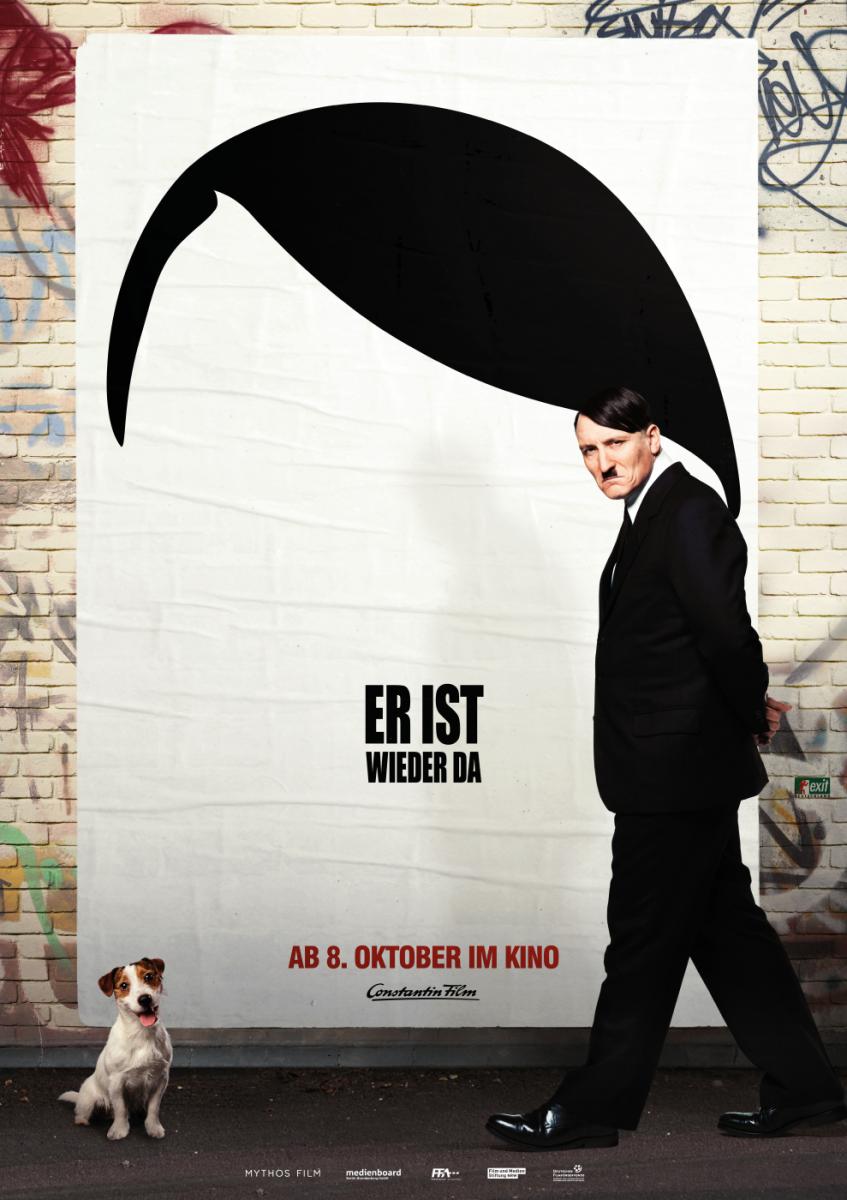

Elie Wiesel had a profound effect on my life. In 1997 I embarked on a journey to earn my Master’s degree from the University of Minnesota. At the time that I began my classes I had no thoughts of studying the Holocaust, but through a series of small events, I found myself thinking of nothing else. I do not remember when I read Night, nor do I recall what led me to return to Wiesel’s work while in graduate school. For some reason I turned to a little known collection of his short stories titled One Generation After, published in 1970. How the book found its way from my mother’s bookshelf to mine is not clear, but for some reason, I picked it up and read it. The story that changed my life was “The Watch.” Over the course of six pages, Wiesel tells of his return to his home of Sighet, Romania and the clandestine mission he undertakes to recover the watch given to him by his parents on the eve of his Bar Mitzvah. It is the last gift he received prior to being transported with his family to Auschwitz. Like many Jewish families, fearing the unknown and hoping for an eventual return, he buried it in the backyard of their home. Miraculously, he finds it, and quickly begins to dream of bringing it back to life. However, in the end he decides to put it back in its resting place. He hopes that some future child will dig it up and realize that once Jewish children had lived and sadly been robbed of their lives there. For Wiesel the town is no longer another town, it is the face of that watch. The idea of reviving a historical figure to return from the dead to our own time period is not new. Many novels and films have dealt with this premise before though usually they focus on the return of someone likable. In the German film

The idea of reviving a historical figure to return from the dead to our own time period is not new. Many novels and films have dealt with this premise before though usually they focus on the return of someone likable. In the German film  Son of Saul is a film about a member of the

Son of Saul is a film about a member of the  Standing on Polish soil is to stand upon the fertile ground of memory. Poles see themselves as a people who have struggled to maintain their national identity amidst occupation and oppression. The Polish past is negotiated on a daily basis between the generations of Poles who lived (or grew up) during World War II, those who lived during the Soviet regime, and those who have come of age after the fall of Communism. All three of these groups have grown up with the narrative of Poles as rescuers, resisters and martyrs. This idea was shaped during the Soviet years and reinforced through Polish popular culture.

Standing on Polish soil is to stand upon the fertile ground of memory. Poles see themselves as a people who have struggled to maintain their national identity amidst occupation and oppression. The Polish past is negotiated on a daily basis between the generations of Poles who lived (or grew up) during World War II, those who lived during the Soviet regime, and those who have come of age after the fall of Communism. All three of these groups have grown up with the narrative of Poles as rescuers, resisters and martyrs. This idea was shaped during the Soviet years and reinforced through Polish popular culture.