Spoil alert! White men are going to take home a lot of Oscars this year. America and the world will once again honor the cult of male genius, and the great men of history.

Spoil alert! White men are going to take home a lot of Oscars this year. America and the world will once again honor the cult of male genius, and the great men of history.

Steven Hawking, Alan Turing, Martin Luther King Jr. – these are some of the great men of this year’s Oscar line-up. Their accomplishments are significant. And kudos to the filmmakers, who, in a few of these cases, complicated the “lone genius” idea by telling a story that reveals the power of mentors, colleagues, and friends. But the genius or the hero is always male, isn’t he?

I still haven’t seen a movie about a woman genius, and I’m wondering if I will in my lifetime. Afterall, our social construction of “genius” is a math-equation-solving white male nerd who is usually associated with an elite institution. We have SO many movies about that guy. Are women ever part of the equation? Isn’t the equation itself reductionist and unfair? Taking this even further, do all geniuses have to use chalkboards, or can we find great thinkers and problem-solvers outside of classrooms?

The genius stereotype isn’t something we let go of when we leave the theater. Fiction shapes real life. Sarah-Jane Leslie is a philosopher at Princeton University who writes in the journal Science that the male genius stereotype is holding women back. And therein lies the challenge – the vicious cycle of fiction shaping reality and vice versa. How can women be called to math, physics, and philosophy, for example, when all we hear about are the great men of these fields?

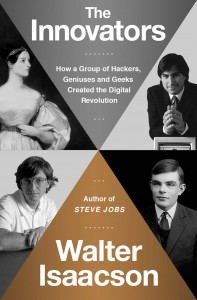

This genius question undergirds Walter Isaacson’s great new book about the forgotten female programmers who created modern technology. Will anyone invest in making this story into a movie, or does it not fit our narrow idea of genius?

It isn’t clear if Oscar-nominated The Theory of Everything pushes the genius trope to the next level. The film doesn’t put a woman in the equation, exactly, but she is nearby. While the film sets us up to follow Steven Hawking’s career and contributions, there next to him in almost every scene is his girlfriend and then wife Jane, who saves him from his depression upon being diagnosed with ALS, and then nurses him and cares for him for not two years (the period of time his doctors give him to live), but decades upon decades, while raising a family and pursuing a PhD. Just as important, she is an educated peer who pushes his thinking. She’s a superwoman! And she speaks to us. What woman doesn’t feel a pang of familiarity watching her balance work and family, thought and emotion? That said, Jane’s load is huge and lonely, especially without her husband’s consent for additional assistance.

In The Theory of Everything, Jane is a type of hero in a film about defying all odds. Still, the film left me feeling like she didn’t get her due. Given her heroism as a caretaker, perhaps Jane should be the one, at the end of the film, who takes the stage and tells us how she did it. Afterall, she appears to be a problem-solving genius. How in the world did she study Spanish literature, raise three kids, care for a severely physically disabled husband, and get food on the table every night?

In The Theory of Everything, Jane is a type of hero in a film about defying all odds. Still, the film left me feeling like she didn’t get her due. Given her heroism as a caretaker, perhaps Jane should be the one, at the end of the film, who takes the stage and tells us how she did it. Afterall, she appears to be a problem-solving genius. How in the world did she study Spanish literature, raise three kids, care for a severely physically disabled husband, and get food on the table every night?

The Theory of Everything enables us to see the great woman behind the great man. But we still have a ways to go before the great women are the stars of the show, and the Oscar recipients.

For a great infographic, see Women’s Media Center on the gendering of this year’s Oscar nominations.

We need to keep critiquing the genius effect. Just for fun, I’m going to start using the word a whole lot more, to describe the women in my life. There are a lot of amazing problem-solvers out there.

uring and after the Anita Hill/ Clarence Thomas trial, a wrinkle that the film does not address.

uring and after the Anita Hill/ Clarence Thomas trial, a wrinkle that the film does not address.