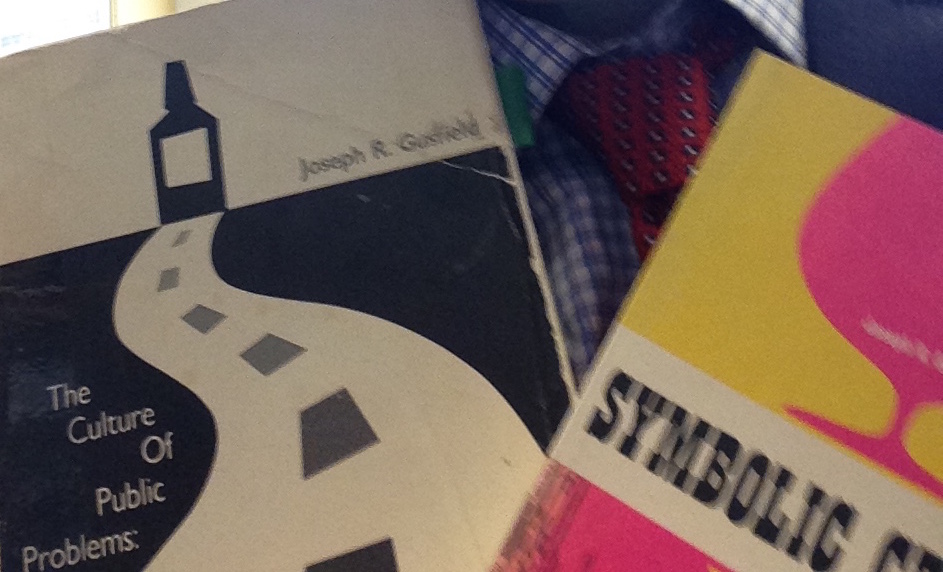

When I first started as a college professor, my father, a play-by-the-rules parochial school teacher and administrator his entire working life, always wanted to know if I wore a tie. It was for him, I think, a symbol of the status and decorum expected of a professional educator, especially one working in our institutions of higher learning. Yesterday, the final day of classes for Spring 2015, I wore a tie. But it was not for my father. It was for one of my graduate school teachers, Joseph Gusfield, who passed away this term in California.

Professor Gusfield was perhaps best known in academia for his first book, Symbolic Crusade, a study that argues that the American Temperance movement was less about moral or even social norms than about a traditional Protestant elite trying to impose and reassert its social status in a rapidly changing nation. For my part (as I’ve written about previously), I find his 1981 book on drinking-driving, The Culture of Public Problems, his best, an under-appreciated classic in both content and style. In it, Gusfield used a range of rhetorical styles (there is a chapter that reads scientific journal articles as an exercise in rhetoric, while another depicts legal studies as actual plays) and types of qualitative and quantitative research to deconstruct conventional understandings of drinking-driving. His primary accomplishment is to show how our usual focus on drinking-driving as the moral failing of individual citizens distracts from the institutional and structural problems of traffic and transportation, leisure-time use, urban design, ambiguities in the law, the power of corporate marketing, and the inherent dangers of driving itself are so very much a part of the “problem” as well.

Gusfield was a great icon in sociology and iconoclast of a professor. I have neither met nor read any other sociologist who was a better, more convincing, or more consistent advocate for sociology as irony than he. With razor sharp intellect and uncompromising belief in sociological information and insight, he embodied, for me, what was so unique and distinctive and intellectually powerful about symbolic interactionism, dramaturgical theory, and California sociology.

Why, then, the tie?

It goes back to the final meeting of the last seminar Gusfield taught at the University of California, San Diego. Somewhat out of character, it seemed, Professor Gusfield wore a tie. “I always wear a tie on the last day of class,” he said. Why? “Because you’ve got to remind everyone who is boss.”

It was a bit jarring to hear from this famously iconoclastic ’60s sociologist who studied social movements, discussed counter-cultures, and always seemed to reject the conventional wisdom. To my recollection, Gusfield went on to explain that in our easy-going, post-1960s, democratic culture—especially in Southern California where many professors wore shorts and t-shirts just like the students—it was easy to forget that we are not all equals, that we all have different roles and responsibilities in the classroom and in society. Though I was surprised at the time, I have long appreciated that non-ironic sociological lesson.

Comments